OCR Specification focus:

‘Devise multi-step routes using transformations between functional groups studied across the specification.’

Multi-stage synthetic routes involve planning a logical sequence of reactions that convert a starting molecule into a target compound. This requires analysing functional groups, selecting appropriate reagents, and ensuring each step is feasible.

Understanding Multi-Stage Synthesis

Designing organic synthetic routes is a fundamental skill in advanced chemistry. Students must understand how functional group interconversions, carbon-chain extensions, and reaction conditions combine to create coherent stepwise pathways. A multi-stage synthesis links numerous reactions already learned across the specification into a new, purposeful order.

Because each step uses known transformations, a successful route must minimise competing reactions, ensure compatibility between functional groups, and anticipate the products of each stage.

Identifying Target Functional Groups

Before designing a sequence, chemists identify all functional groups in the target molecule. Recognising which groups must be introduced, removed, or altered is essential.

Functional Group: A specific arrangement of atoms within a molecule that gives characteristic chemical properties and reactivity.

Once the functional groups are clear, the route can be broken into distinct transformations. One must also look for features such as changes in oxidation level, chain length, stereochemistry, and whether substituents have moved or been substituted.

Normal sentence between blocks: Functional group recognition also helps determine whether reagents must be acidic, basic, reducing, oxidising, or anhydrous.

Mapping Backwards (Retrosynthetic Thinking)

A common approach is to work backwards from the target molecule.

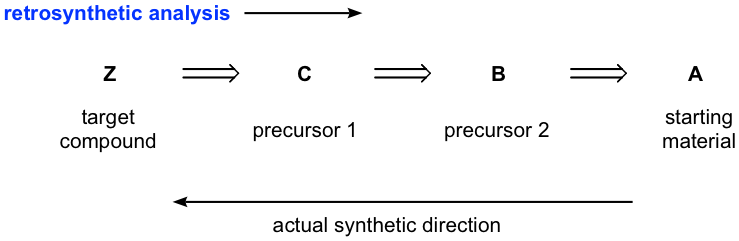

This diagram shows retrosynthetic analysis, where the target compound is simplified stepwise into plausible precursors using backward-pointing arrows, helping plan a multi-stage synthesis before writing the forward route. Source

This method asks what precursor could reasonably produce the target via a single, known transformation. Repeating this creates a chain of feasible steps.

Features of Effective Retrosynthesis

Identify the final functional group change required.

Determine which previous step could form that group.

Continue simplifying until reaching a readily available starting material.

Ensure that conditions for one step do not destroy functional groups created earlier.

Consider alternative pathways if a step is chemically unrealistic.

Retrosynthesis trains students to view molecules as interconnected transformations rather than isolated structures.

Functional Group Interconversions (FGIs)

FGIs lie at the heart of multi-stage routes. A route commonly includes oxidation, reduction, substitution, hydrolysis, and condensation reactions. OCR students must recall the conditions and reagents that enable these.

Key OCR-Relevant Transformations

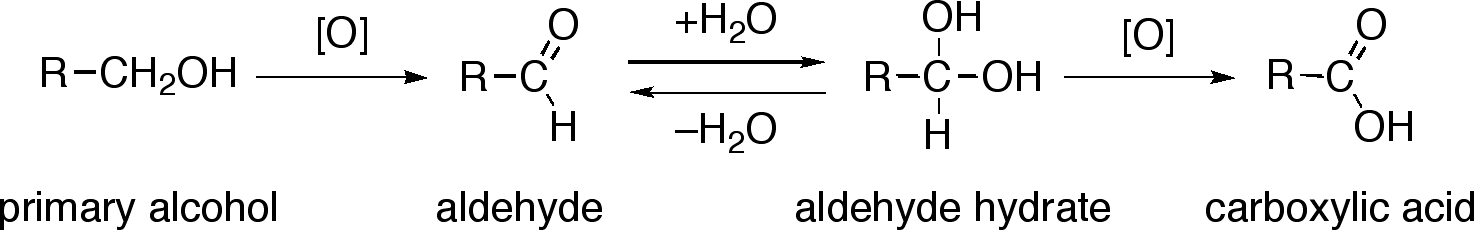

Oxidation: alcohol → aldehyde → carboxylic acid

This scheme illustrates the stepwise oxidation of a primary alcohol to an aldehyde and then to a carboxylic acid, highlighting controlled changes in oxidation state used in multi-stage synthesis. Source

Reduction: nitrile → amine; ketone/aldehyde → alcohol

Substitution: haloalkane → amine; haloalkane → nitrile

Hydrolysis: ester → alcohol + acid; amide → acid + ammonium salt

Condensation: formation of esters or amides from acids or acyl chlorides

Aromatic substitution under Friedel–Crafts conditions to extend carbon chains

The specification emphasises that choosing FGIs must reflect transformations already studied, as multi-stage synthesis draws solely on known reactions.

Chain Length Changes

Multi-stage synthesis often requires extending or shortening the carbon chain.

Carbon-Chain Extension: A reaction that increases the number of carbon atoms in a molecule, often by nucleophilic substitution using cyanide ions or carbonyl addition with HCN.

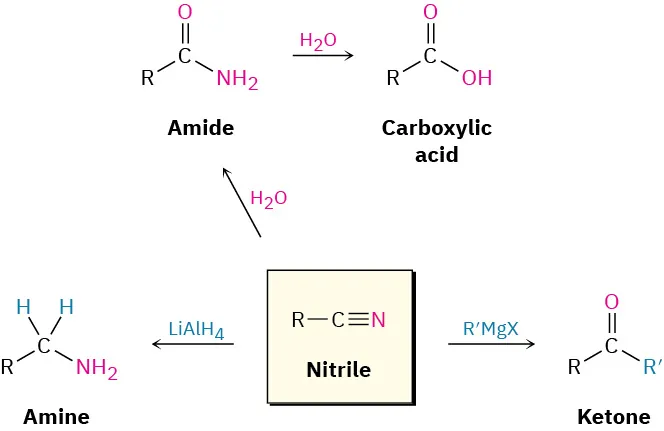

Students must recognise which reactions link new carbon atoms into molecules. Common OCR-approved methods include nucleophilic substitution of haloalkanes with CN⁻ and addition of HCN to carbonyls. After extension, nitriles can be reduced to amines or hydrolysed to carboxylic acids, enabling further transformations.

This diagram shows nitriles as versatile intermediates, including hydrolysis to carboxylic acids and reduction to amines. The pathway to ketones using Grignard reagents is shown but goes beyond the required syllabus content. Source

A normal sentence separates the blocks. Carbon-chain extension steps frequently appear early in a route to generate intermediates suitable for later FGIs.

Reagent and Condition Selection

Every synthesis step requires careful selection of reagents and conditions. Students must remember the specificities of reagents such as H₂/Ni, NaBH₄, aqueous acid, ethanolic ammonia, and acyl chlorides. Choosing incorrect conditions may convert molecules into undesired products or destroy groups required for later steps.

Considerations When Selecting Reagents

Selectivity: Will the reagent transform only the intended group?

Compatibility: Are other functional groups stable under these conditions?

Order of Steps: Does the route avoid creating reactive groups too early?

Purification Feasibility: Are the products separable before the next step?

Multi-stage synthesis always aims to maintain control and avoid side reactions.

Using Protecting Groups (When Relevant)

OCR does not heavily emphasise protecting group chemistry, but students should recognise the general concept: sometimes a functional group must remain unchanged while another reacts. For example, an alcohol might be incompatible with strong reagents used elsewhere. When necessary, temporary protection ensures the rest of the molecule undergoes the desired transformation.

Normal sentence: Although protecting groups are not widely required in OCR exam questions, the idea reinforces why reaction order matters.

Designing Routes Using Known Reactions

Chemists plan multi-step routes using only the reactions already taught. The specification explicitly requires students to devise multi-step routes by linking transformations across the course. Syntheses may involve:

turning acids into esters, amides, or acyl chlorides

converting alcohols to haloalkanes or carbonyl compounds

transforming nitriles into amines or acids

forming aromatic derivatives through electrophilic substitution

interchanging between amines, amides, and carboxylic acid derivatives

combining condensation and hydrolysis steps to modify polymer-forming functional groups

Each transformation must logically prepare the molecule for the next stage.

Integrating Mechanisms

While the focus is on designing routes rather than giving mechanisms, understanding the mechanism supports the ability to judge feasibility. Knowledge of nucleophilic substitution, nucleophilic addition, electrophilic substitution, and condensation helps predict intermediate structures and potential problems.

Constructing Coherent Reaction Sequences

Effective multi-stage synthesis relies on linking steps so the product of one becomes the substrate of the next. A well-designed pathway should:

proceed in a chemically realistic order

use reagents compatible with all existing functional groups

change only one feature at a time

avoid unnecessary detours

incorporate efficient chain-length or functional-group changes early

end with a clean formation of the target molecule’s distinctive group

This methodical approach supports mastery of complex synthetic planning and fulfils the OCR requirement for constructing clear, justified multi-step routes.

FAQ

The order determines whether functional groups survive each step and whether intermediates can form successfully.

Some reactions use harsh conditions, such as strong acids, bases, or reducing agents, which may destroy functional groups formed earlier. Planning the correct sequence ensures sensitive groups are introduced later, reducing side reactions and improving overall yield.

Carbon-chain extension is included when the target molecule has more carbon atoms than the starting material.

This step is usually placed early in the route so the extended chain can undergo further functional group transformations. Common OCR-relevant extensions use cyanide ions or HCN, which form versatile intermediates suitable for later reactions.

A suitable intermediate must be chemically stable under the conditions required for the next step.

It should contain the correct functional group for further transformation and avoid unnecessary reactivity. Intermediates that are easy to purify and isolate are preferred, as this reduces errors and improves the efficiency of the overall synthesis.

Working backwards helps identify the most direct and realistic transformations needed to form the target molecule.

This approach allows chemists to focus on the final functional group change first and then select known reactions that lead to it. Backward planning reduces unnecessary steps and helps avoid routes that are chemically unrealistic.

Mechanisms explain how bonds break and form during a reaction, helping predict whether a step will work as intended.

Understanding mechanisms helps chemists anticipate competing reactions, rearrangements, or incomplete conversions. This insight improves reagent selection and ensures each stage of the synthesis leads logically to the next.

Practice Questions

A student wishes to synthesise ethanol from chloroethane using a two-step route.

State two changes the student must make when planning a multi-stage synthetic route rather than a single-step reaction.

(2 marks)

Award 1 mark for each valid point, up to a maximum of 2 marks.

Identify the need to consider intermediate compounds formed between steps

Recognise that reagents and conditions must be compatible with existing functional groups

State that the order of reactions must be planned carefully to avoid unwanted side reactions

Mention that purification may be required between stages

Any two correct points gain full marks.

A student is asked to design a multi-stage synthetic route to convert 1-bromopropane into propanoic acid.

Describe a suitable two-step route, including:

the reagents and conditions used in each step

the functional group changes that occur at each stage

You are not required to write full equations.

(5 marks)

Award marks as follows:

Step 1: Carbon-chain transformation (2 marks)

1 mark for using potassium cyanide (or sodium cyanide) in ethanol to convert 1-bromopropane into a nitrile

1 mark for correctly identifying the functional group change from haloalkane to nitrile

Step 2: Functional group interconversion (2 marks)

1 mark for hydrolysing the nitrile using aqueous acid and heat to form a carboxylic acid

1 mark for identifying the functional group change from nitrile to carboxylic acid

Overall synthesis planning (1 mark)

1 mark for a logically ordered, feasible two-step route that leads to propanoic acid

Marks may be awarded for clearly described reagents and conditions even if chemical names are not perfectly stated.