OCR Specification focus:

‘Construct balanced chemical equations, including state symbols, for studied reactions and unfamiliar reactions given sufficient information.’

Balancing chemical equations is a fundamental skill in A-Level Chemistry, allowing students to represent chemical reactions accurately, conserve mass, and demonstrate understanding of reacting species and their physical states.

Introduction

Balancing chemical equations ensures chemical reactions are represented accurately, conserving atoms and charge. Including state symbols provides vital information about physical states essential for interpreting reaction behaviour.

Understanding Chemical Equations

A chemical equation shows the reactants that undergo change and the products formed. It must obey the law of conservation of mass, meaning the total number of atoms of each element is the same on both sides.

Key Components of a Chemical Equation

When constructing or interpreting a chemical equation, always identify:

The reactants and products.

The correct chemical formulae for each species.

The stoichiometric coefficients, which represent the ratio in which species react.

The state symbols, which provide information on physical states essential for clarity.

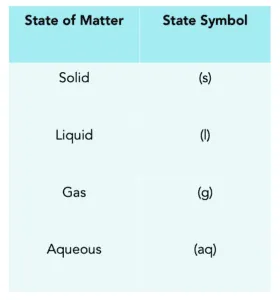

State symbols required at A-Level include:

(s) for solid

(l) for liquid

(g) for gas

(aq) for aqueous (dissolved in water)

This table summarises the state symbols used in chemical equations, providing a clear reference for interpreting physical states in reactions. Source

(aq) for aqueous (dissolved in water)

These symbols allow you to understand conditions, solubility, and reaction pathways.

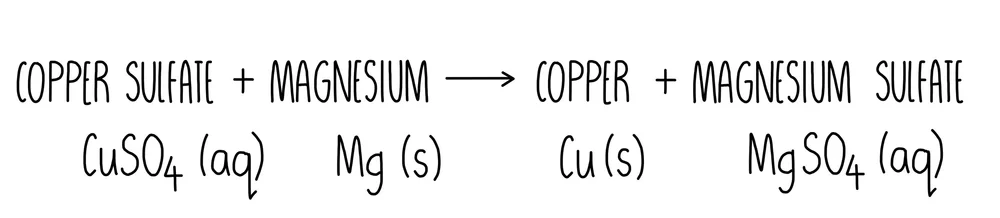

This diagram shows a word and symbol equation with full state symbols, reinforcing how physical states are represented in balanced chemical equations. Source

Balanced Chemical Equation

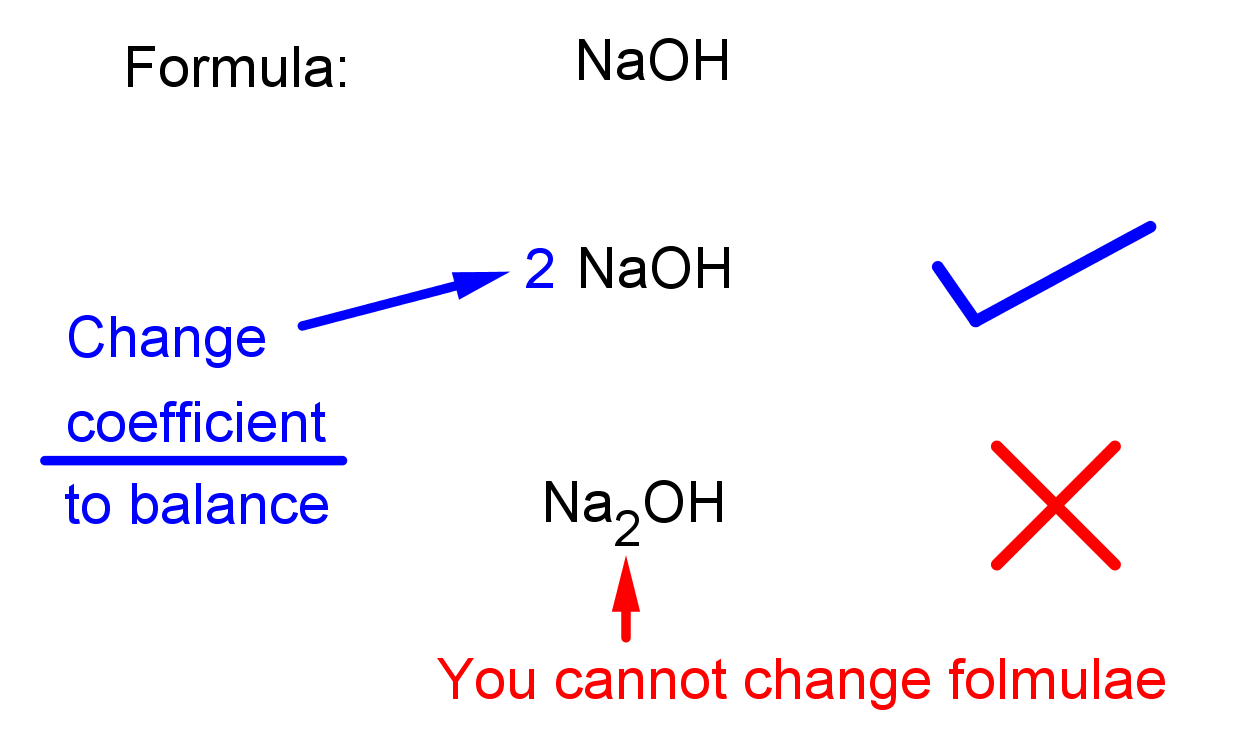

A balanced equation has equal numbers of each type of atom on both sides. Balancing does not involve changing chemical formulae, only altering coefficients.

This image compares an unbalanced and a correctly balanced equation, emphasising that only coefficients may be changed while formulae must remain unchanged. Source

Students must balance familiar and unfamiliar reactions when supplied with adequate information.

Stoichiometric Coefficient: A number placed before a formula in an equation showing the mole ratio of reactants and products.

Balancing coefficients correctly is vital for interpreting quantitative relationships in chemical reactions, later used in calculations involving moles, percentage yields, and titration data.

Methods for Balancing Chemical Equations

The OCR specification requires the ability to construct balanced equations, including those that may involve unfamiliar species. A systematic approach prevents errors and improves efficiency.

Systematic Balancing Approach

Use the following structured process:

Identify all reactants and products, writing their correct formulae.

List all atoms involved in the reaction.

Begin balancing with the element that appears in the fewest formulae.

Balance atoms one element at a time by adjusting coefficients.

Leave hydrogen and oxygen until the end, as they often appear in multiple species.

Ensure coefficients are in the simplest whole-number ratio.

Add state symbols based on data provided or standard chemical behaviour.

After balancing, a final check is essential to confirm atom equality and correct charges where ions are involved.

State Symbols and Their Importance

Adding state symbols ensures chemical equations convey full scientific meaning. They indicate physical state and can affect reaction pathways, solubility, and whether a precipitate forms. This is a required skill in the OCR A-Level course.

Some useful principles:

Ionic compounds in solution use (aq).

Precipitates formed in reactions are labelled (s).

Covalent liquids like water use (l).

Many gases formed in reactions (e.g., hydrogen, carbon dioxide) use (g).

Including correct state symbols becomes particularly important when writing equations for precipitation reactions, neutralisation, and gas evolution reactions.

Common Challenges When Balancing Equations

Balancing can be complicated by polyatomic ions, unfamiliar reactants, or multiple products. Developing strategies to overcome these issues is essential.

Polyatomic Ions as Units

In many reactions, polyatomic ions such as SO₄²⁻, NO₃⁻, or CO₃²⁻ appear unchanged on both sides. In these cases, treat the ion as a single unit when balancing. This simplifies the process and reduces time spent balancing individual atoms.

Species Containing Oxygen and Hydrogen

Because oxygen and hydrogen occur frequently in several reactants and products, place them late in the balancing sequence. Their distribution often adjusts automatically once other elements are balanced.

Checking Ionic Charges in Aqueous Reactions

Although this subsubtopic focuses on full equations rather than ionic equations, some reactions contain ions whose charges must be consistent before balancing coefficients. Ensuring consistency helps avoid errors, especially when writing equations involving acids, alkalis, or salts.

State Symbol: A notation indicating the physical state of a substance in a chemical equation, such as (s), (l), (g), or (aq).

Correctly identifying state symbols strengthens understanding of reaction conditions and supports later learning in solubility rules, redox processes, and acid–base chemistry.

Writing Balanced Equations for Unfamiliar Reactions

The specification emphasises constructing balanced equations even for unfamiliar reactions when enough information is provided. When presented with such scenarios:

Use the information provided about products, reactants, or observations (e.g., gas evolution, precipitate formation).

Deduce likely species based on typical chemical behaviour.

Apply standard formulae for ions or compounds commonly encountered.

Follow balancing rules methodically.

Add correct state symbols based on the context or solubility knowledge.

Through careful interpretation and systematic balancing, even unfamiliar reactions become manageable and logical within OCR A-Level expectations.

FAQ

Balancing atoms ensures that the same number of each element appears on both sides of the equation. This reflects the conservation of mass.

Balancing charge is only necessary when species carry ionic charges. The sum of charges on the reactant side must equal the sum on the product side.

In full chemical equations (not ionic equations), charge balancing is often achieved automatically when atoms are correctly balanced.

A useful strategy is:

Start with the element that appears in the fewest substances.

Balance metals before non-metals.

Leave oxygen and hydrogen until last because they commonly appear in multiple species.

This approach reduces repeated adjustments later and helps avoid unbalancing previously balanced atoms.

More than one balanced equation may be acceptable if all coefficients are in the simplest whole-number ratio.

For example, doubling or halving all coefficients still represents the same reaction, but examiners require the simplest ratio.

Different balanced versions may appear when students choose different starting points, but all correct answers conserve atoms and use valid coefficients.

Knowing which compounds dissolve in water allows you to assign (aq) or (s) accurately.

General guidance:

Most nitrates are soluble.

Most group 1 and ammonium compounds are soluble.

Most carbonates and hydroxides are insoluble, except group 1 and ammonium salts.

Many sulphates are soluble, with exceptions like barium sulphate and lead(II) sulphate.

These rules help predict whether a species forms a precipitate or remains dissolved.

A balanced equation provides the mole ratios needed for calculations involving reactants and products.

Without a correctly balanced equation:

Stoichiometric ratios become inaccurate.

Yields, concentrations, and gas volumes cannot be calculated reliably.

Reactions may appear to require incorrect amounts of substances.

Accurately balanced equations underpin all mole-based and proportional reasoning in A-Level Chemistry.

Practice Questions

Write a balanced chemical equation, including state symbols, for the reaction between aqueous hydrochloric acid and solid calcium carbonate to produce aqueous calcium chloride, liquid water, and carbon dioxide gas. (2 marks)

Required balanced equation:

CaCO3(s) + 2HCl(aq) → CaCl2(aq) + H2O(l) + CO2(g)

Mark breakdown:

1 mark: Correct formulae for all reactants and products with correct state symbols.

1 mark: Correct balancing (1 Ca, 1 C, 3 O on both sides; 2 HCl).

The following unbalanced equation represents the reaction between iron(III) oxide and carbon monoxide to form iron and carbon dioxide:

Fe2O3(s) + CO(g) → Fe(s) + CO2(g)

(a) Balance the equation. (2 marks)

(b) Explain why it is important that only coefficients, and not chemical formulae, are changed when balancing equations. (2 marks)

(c) State the state symbols for iron(III) oxide and carbon monoxide, giving one reason for each. (1 mark)

(5 marks)

(a) Balanced equation:

Fe2O3(s) + 3CO(g) → 2Fe(s) + 3CO2(g)

1 mark: Correct balancing of iron (2 Fe atoms).

1 mark: Correct balancing of carbon and oxygen (3 CO producing 3 CO2).

(b) Explanation:

Any two of:

Changing subscripts would alter the identity of a substance. (1 mark)

Chemical formulae represent fixed ratios of atoms in a compound. (1 mark)

Only coefficients can be changed because they represent the number of particles reacting, which preserves chemical identity. (1 mark, max 2)

(c) State symbols:

Iron(III) oxide is a solid because it is an ionic lattice compound with high melting point. (0.5 mark)

Carbon monoxide is a gas because it exists as small covalent molecules with low intermolecular forces. (0.5 mark)