OCR Specification focus:

‘Construct balanced ionic equations for relevant reactions, showing only the species that undergo change.’

Introduction

Ionic equations simplify chemical reactions by showing only the reacting ions, highlighting the essential chemical changes and removing ions that remain unchanged throughout the process.

Understanding Ionic Equations

Ionic equations are an essential tool in analysing reactions that occur in aqueous solution. They focus on the actual chemical change rather than the complete molecular equation. To construct them effectively, it is necessary to identify ions present, determine which species undergo chemical change, and remove those that do not participate.

What Are Ionic Species?

When ionic compounds dissolve in water, they separate into charged particles called ions, forming an aqueous solution capable of conducting electricity. Understanding the behaviour of ions in solution is crucial for writing ionic equations correctly, as only aqueous ionic species can be separated into individual ions.

Ionic Equation: A chemical equation showing only the ions and molecules directly involved in the chemical change, excluding spectator ions.

Ionic equations offer insight into reaction mechanisms by isolating the essential particles undergoing oxidation, reduction, acid–base neutralisation, or precipitation. They are widely used across inorganic chemistry, especially in redox and acid–base processes.

Spectator Ions

During a reaction in solution, some ions do not undergo any chemical change. These unchanged ions are known as spectator ions, and identifying them allows the ionic equation to be simplified correctly.

Spectator Ion: An ion present in the reaction mixture that remains unchanged in both physical state and chemical form before and after the reaction.

A single sentence of explanation helps consolidate this definition before advancing. Spectator ions commonly appear in displacement reactions, precipitation reactions, and neutralisations where only a subset of ions take part in the transformation.

Constructing Ionic Equations

Writing correct ionic equations is a systematic process. Each step ensures that the final equation includes only reacting species and remains fully balanced for both mass and charge.

Step-by-Step Approach

Follow the structured approach below to construct accurate ionic equations:

Write the full balanced chemical equation.

This is the complete molecular equation showing all reactants and products.

Identify aqueous ionic species.

Only substances in the (aq) state should be split into ions. Solids, liquids, and gases remain intact.

Separate aqueous ionic compounds into their constituent ions.

This produces the full ionic equation, which includes all ions present in the reaction environment.

Determine which ions undergo change.

Compare ions on both sides to identify which participate in the reaction.

Remove spectator ions.

These ions appear unchanged on both sides and must not be included in the final ionic equation.

Check for charge and atom balance.

An ionic equation must be balanced in terms of both mass and overall charge.

Representing Ions Clearly

In ionic equations, ions should be written with correct charge notation, such as Cl⁻, Mg²⁺, or SO₄²⁻, ensuring clarity in identifying charge changes. For polyatomic ions that remain intact during the reaction, they should be written as complete units rather than separated into elements.

A clear understanding of state symbols is essential here, as these affect whether substances are written as ions or molecules.

State Symbols in Ionic Equations

Correct use of state symbols ensures that ionic equations remain chemically accurate:

(aq) indicates substances that dissociate into ions.

(s) indicates solids and precipitates, which remain intact.

(l) is used for pure liquids such as water.

(g) represents gases.

A precipitate formed in a reaction must be written as a solid, never as ions, because the ions have combined to produce an insoluble compound.

To obtain a net ionic equation, you remove the spectator ions and write only the species that undergo change during the reaction.

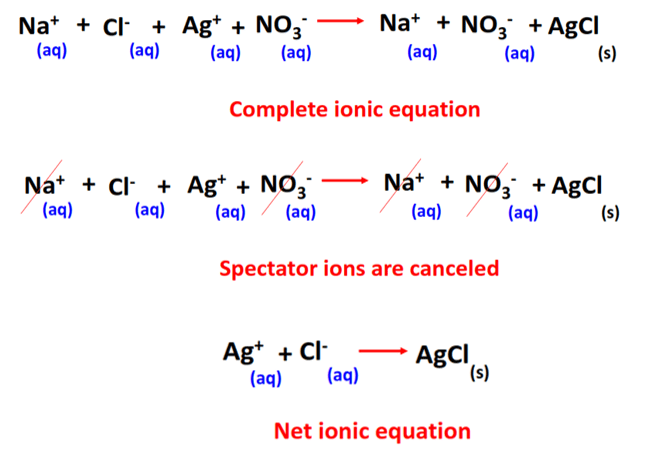

This image shows the complete ionic equation, cancellation of spectator ions, and the resulting net ionic equation for the AgNO₃ and NaCl reaction, highlighting ions that participate and those that remain unchanged. Source

Importance of Ionic Equations

Ionic equations reveal the underlying chemistry more clearly than full equations. They highlight:

Electron transfer in redox reactions.

Proton transfer in acid–base reactions.

Formation of a precipitate from dissolved ions.

Displacement processes involving metals or halogens.

By focusing exclusively on the reacting particles, ionic equations support better conceptual understanding and chemical reasoning at A-Level.

Charge Balance and Chemical Accuracy

Charge conservation is a fundamental requirement. The total charge on the left-hand side of the ionic equation must equal the total charge on the right-hand side. This reflects the principle that charge cannot be created or destroyed in a chemical process.

Charge Balance: The requirement that the sum of ionic charges on each side of an ionic equation must be equal.

This principle reinforces the importance of writing ions with correct charges and checking for overall balance.

Spectator ions must have the same formula, charge and state on both sides of the ionic equation.

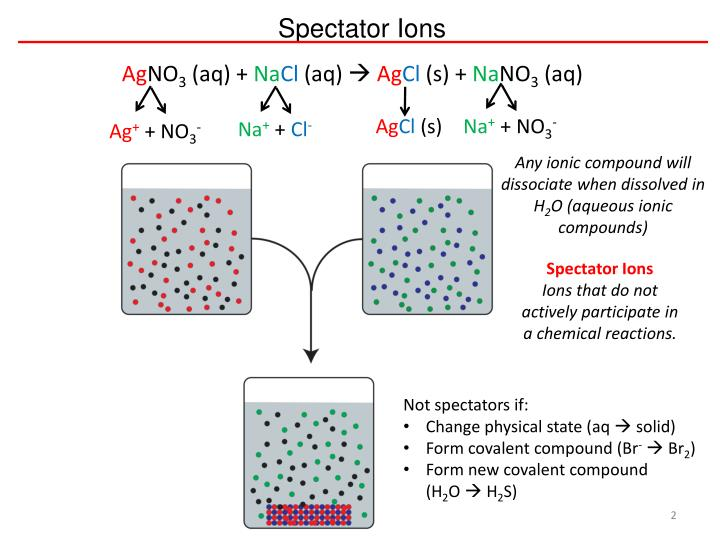

This diagram visualises the ions present before and after mixing solutions, highlighting that sodium and nitrate ions remain unchanged as spectator ions while silver and chloride form a precipitate. Source

Applying the Concept Across Reactions

This subsubtopic appears throughout OCR A-Level Chemistry because many aqueous reactions require ionic representation. Students will encounter ionic equations when studying acids and bases, precipitation tests, redox processes, halogen displacement reactions, and qualitative analysis. The ability to construct accurate ionic equations is therefore an essential skill for mastering later content in the course.

When ionic compounds dissolve in water, they dissociate into free-moving aqueous ions, so in ionic equations these species are written as separate ions rather than as whole formula units.

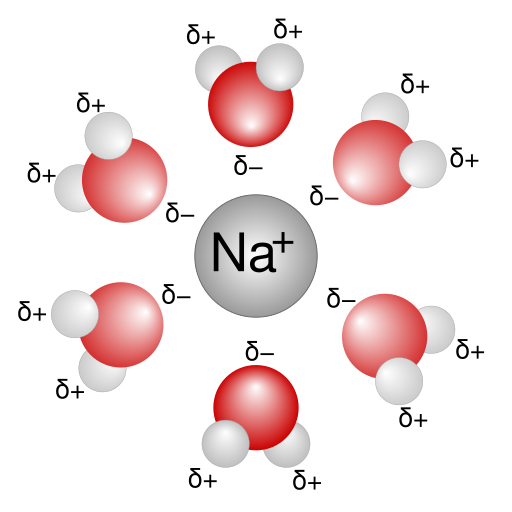

This diagram illustrates a sodium ion surrounded by water molecules in a solvation shell, reinforcing why ions behave as separate species in aqueous solution; partial charge labels represent extra detail beyond the specification. Source

FAQ

An ion is written separately only if the substance is both ionic and aqueous. Ionic solids, gases, and liquids must remain as whole formula units.

Polyatomic ions such as sulfate or nitrate are kept together unless the reaction specifically breaks them apart, which rarely occurs in precipitation or neutralisation reactions.

Yes. A species might appear different in the full equation but still not undergo a real chemical change.

For example, ions that change partners in a double displacement reaction but remain in the aqueous phase with identical charge and formula are still spectator ions.

This occurs when all ions present participate directly in the chemical change.

Typical examples include

acid–base neutralisations involving hydrogen and hydroxide ions

reactions where no ions remain unchanged on both sides

Such cases show that no spectator ions are present

List all ions on each side, matching charge and state.

Spectator ions will:

appear on both sides unchanged

have identical coefficients

remain aqueous throughout

Removing these leaves only reacting species.

State symbols determine whether a substance is eligible to be split into ions.

Only aqueous substances dissociate. Solids, liquids, and gases must remain intact, so incorrectly assigning (aq) may lead to splitting molecules that do not actually ionise and producing invalid ionic equations.

Practice Questions

Aqueous solutions of barium nitrate and sodium sulfate are mixed.

(a) Write the ionic equation for the reaction that forms a precipitate.

(b) Identify the spectator ions.

(2 marks)

(a) Ionic equation

Ba2+ (aq) + SO4 2– (aq) → BaSO4 (s)

1 mark for correct ions on the left-hand side

1 mark for correct solid precipitate on the right-hand side

(b) Spectator ions

Na+ (aq) and NO3– (aq)

Identification of both spectator ions = 1 mark

(If part (a) already awarded full marks, part (b) still requires both ions for the mark.)

A student mixes aqueous aluminium nitrate with aqueous sodium hydroxide. A white precipitate forms.

(a) Write the full ionic equation for the reaction.

(b) Deduce the net ionic equation.

(c) Explain why the ions you removed are considered spectator ions.

(d) State one reason why ionic equations are preferred over full molecular equations when analysing reactions in solution.

(5 marks)

(a) Full ionic equation

Al3+ (aq) + 3OH– (aq) → Al(OH)3 (s)

1 mark for correct aluminium ion

1 mark for correct hydroxide ions and stoichiometry

1 mark for correct precipitate formula and state symbol

(b) Net ionic equation

Al3+ (aq) + 3OH– (aq) → Al(OH)3 (s)

1 mark (same as full ionic equation because all ions participate)

(c) Explanation of spectator ions

1 mark for stating that spectator ions are unchanged in state, formula and charge

1 mark for identifying that nitrate and sodium ions do not appear in the net ionic equation because they undergo no chemical change

(d) Reason for using ionic equations

1 mark for a clear reason, e.g. “They show only the species that undergo chemical change and simplify the reaction to its essential process.”