OCR Specification focus:

‘Define neutralisation as H+ reacting with OH– to form H2O; acids react with carbonates, metal oxides and alkalis to form salts.’

Neutralisation and salt formation are central reactions in acid–base chemistry, underpinning many laboratory processes, analytical techniques and industrial applications. Understanding how acids react with different classes of compounds allows chemists to predict products, write equations confidently and apply these reactions in quantitative contexts such as titrations.

Neutralisation: The Core Concept

Neutralisation refers specifically to the reaction between H+ (aq) ions from an acid and OH– (aq) ions from an alkali to form H2O (l). This process is fundamental to acid–base chemistry and forms the basis of many analytical procedures involving titrations and standard solutions.

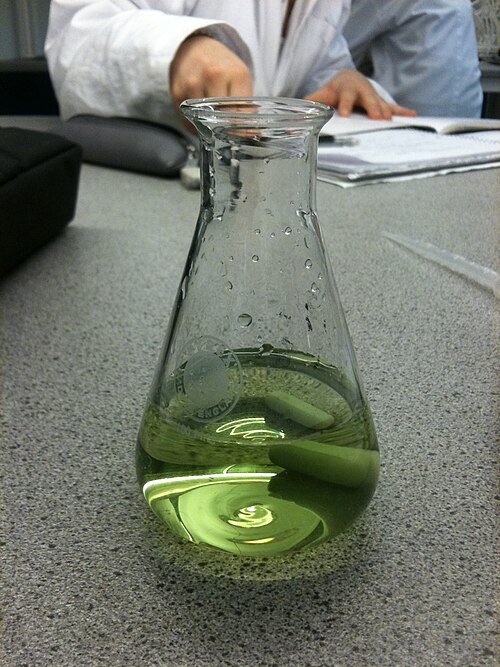

Aqueous hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide are mixed with bromothymol blue indicator to show a neutralisation reaction. At the equivalence point, the solution becomes green, indicating a neutral solution where acid and alkali have reacted to form salt and water. The indicator detail is additional but helps visualise completion of neutralisation. Source

Neutralisation: The reaction of H+ (aq) with OH– (aq) to form H2O (l).

A key feature of neutralisation is that it involves the removal of acidic protons by hydroxide ions, resulting in the formation of water. This transformation underlies the thermal changes observed when acids and alkalis are mixed and explains why strong acid–strong base titration curves display a characteristic pH rise near the equivalence point.

Formation of Salts

A salt is formed when the hydrogen ion of an acid is replaced by a metal ion, ammonium ion or another positive ion. The nature of the salt produced always depends on both the acid used and the reacting species providing the positive ion.

General rules for products formed in acid reactions:

Acid + alkali → salt + water

Acid + metal oxide → salt + water

Acid + metal carbonate → salt + water + carbon dioxide

Acid + metal → salt + hydrogen

Each acid forms a characteristic salt type:

Hydrochloric acid forms chlorides

Sulfuric acid forms sulfates

Nitric acid forms nitrates

Ethanoic acid forms ethanoates

A normal sentence is required here before the next definition to maintain appropriate spacing and ensure clarity in the presentation of material.

Salt: A compound formed when hydrogen ions in an acid are replaced by metal ions or ammonium ions.

Reactions of Acids with Alkalis

This is the simplest case of neutralisation, involving proton transfer from the acid to the hydroxide ion. These reactions take place in aqueous solution and are widely used in titrations.

Key features of acid–alkali reactions:

Always produce water as a product.

Form a salt determined by the acid anion and the metal cation in the alkali.

Common alkalis include NaOH, KOH, and NH3 (aq), which act as sources of OH– (aq) either directly or through reaction with water.

Bullet points describing the further implications of these reactions:

The ionic equation for all strong acid–strong base reactions is identical: H+ (aq) + OH– (aq) → H2O (l).

Weak alkalis such as ammonia produce hydroxide ions through partial dissociation or reaction with water.

The pH change observed depends on the strengths of the acid and alkali.

Reactions of Acids with Metal Oxides

Metal oxides are basic in nature and act as proton acceptors. When metal oxides react with acids, they typically undergo neutralisation.

Important points:

Products are salt + water.

Many metal oxides are insoluble, so reactions may require heating to ensure completion.

The reaction provides a key route to preparing solid salts in the laboratory.

Common metal oxides involved include:

Copper(II) oxide

Magnesium oxide

CaIcium oxide

These reactions frequently feature in practical preparations of salts where insoluble bases are preferred due to their ease of separation from reaction mixtures.

Reactions of Acids with Metal Carbonates

Metal carbonates contain the CO3²– ion and display a characteristic reaction pattern with acids. These reactions release carbon dioxide gas, allowing for easy identification.

Key features of acid–carbonate reactions:

Products: salt + water + carbon dioxide

Effervescence is observed due to CO2 gas production.

These reactions are commonly used to test for the presence of carbonates.

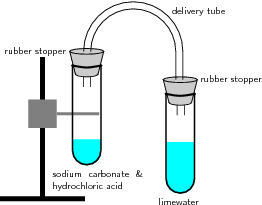

This diagram shows an acid–carbonate reaction where carbon dioxide gas is generated and bubbled into limewater. The limewater turns milky as insoluble calcium carbonate forms, confirming CO₂ production. This analytical detail supports the general reaction pattern acid + carbonate → salt + water + carbon dioxide. Source

Bullet points illustrating specific properties:

Metal hydrogencarbonates react similarly but may show slightly different stoichiometry.

The CO2 produced can be identified using limewater, which forms a milky suspension of calcium carbonate.

Rates of reaction vary depending on the solubility and surface area of the carbonate.

A sentence is inserted here to maintain structural flow before introducing any further structured material.

Reactivity Considerations in Salt Formation

Different classes of compounds react with acids at different rates and under different conditions. Understanding these helps predict experimental outcomes and informs laboratory technique.

Factors influencing reaction behaviour:

Solubility of the base or carbonate affects reaction speed.

Strength of the acid, with stronger acids providing more immediate proton availability.

Temperature, as warming can increase reaction rates for insoluble oxides.

Bullet-pointed patterns observed in the laboratory:

Strong acids react vigorously with carbonates, producing rapid effervescence.

Reactions with metal oxides may be slower but typically yield high-purity salts.

Using excess base ensures full consumption of the acid when preparing salts.

Naming and Predicting Salt Products

Accurate naming of salts is essential in chemical equation writing. The salt formed is determined by the acid’s anion and the cation supplied by the reacting substance.

Rules for naming salts:

The first part of the name comes from the metal or ammonium ion.

The second part comes from the acid:

HCl → chloride

H2SO4 → sulfate

HNO3 → nitrate

CH3COOH → ethanoate

Predicting formulae requires attention to ion charges and combining ratios to produce neutral compounds.

These principles allow students to construct balanced chemical equations confidently and recognise neutralisation as the unifying theme linking these important reactions.

FAQ

Stronger acids dissociate more fully, providing a higher concentration of H+ ions, which increases the rate at which they react with bases, oxides or carbonates.

However, the stoichiometry of neutralisation does not change, as one H+ still reacts with one OH–. The difference appears only in reaction speed, not in the products formed.

Many metal oxides, such as copper(II) oxide, are insoluble and have low surface reactivity at room temperature. Heating increases particle kinetic energy, improving contact between oxide surfaces and acidic solution.

This ensures complete neutralisation and reduces reaction time, especially when preparing crystalline salts.

Solubility depends on the identity of both ions forming the salt. For example:

Most sodium, potassium and ammonium salts are soluble.

Many carbonates and hydroxides are insoluble.

Some sulfates (e.g., calcium sulfate) have low solubility.

These solubility patterns influence whether filtration or evaporation is required to isolate the salt.

Carbonate ions release carbon dioxide gas upon reacting with H+ ions. Because CO2 is poorly soluble in water, it escapes rapidly as bubbles.

Effervescence continues only while both reactants are available. Once the acid is fully consumed, bubbling ceases, making this a useful indicator of reaction completion.

Purity improves when:

The base is added in excess to ensure all acid is neutralised.

The mixture is warmed only gently to avoid decomposition of heat-sensitive salts.

Filtration is carried out carefully to remove every trace of unreacted solid.

Slow crystallisation is used to allow well-formed, pure crystals to develop.

These steps prevent contamination from leftover base or partially reacted material.

Practice Questions

A student adds excess sodium carbonate to dilute hydrochloric acid.

(a) State the three products formed in this reaction.

(b) Give one observation the student would see during the reaction.

(2 marks)

(a) Products:

Salt (specifically sodium chloride) (1)

Water (1)

Carbon dioxide (1)

(Max 2 marks)

(b) Observation:

Effervescence / fizzing / bubbles (1)

(Only one needed)

A teacher asks students to describe how salts can be formed using reactions of acids with different types of compounds.

Explain, with equations, how a pure dry sample of a salt can be prepared using:

(a) an acid and an insoluble metal oxide

(b) an acid and a metal carbonate

In each case, outline the essential steps needed to obtain the solid salt.

(5 marks)

General marking guidance: equations can be balanced ionic or full chemical equations.

(a) Acid + metal oxide → salt + water

Correct general reaction statement or correct equation, e.g.

hydrochloric acid + copper(II) oxide → copper(II) chloride + water (1)

Metal oxide is insoluble and added in excess to ensure all acid is used (1)

Mixture warmed to increase reaction rate (1)

Excess oxide filtered off to obtain salt solution (1)

(b) Acid + carbonate → salt + water + carbon dioxide

Correct general reaction statement or correct equation, e.g.

nitric acid + magnesium carbonate → magnesium nitrate + water + carbon dioxide (1)

Effervescence due to CO2 release is observed (1)

Add carbonate until bubbling stops, showing all acid has reacted (1)

Filter off any remaining solid carbonate (1)

Maximum: 5 marks