OCR Specification focus:

‘Carry out structured and unstructured titration calculations using experimental results for familiar and unfamiliar acids and bases.’

Titration calculations form a core quantitative skill in A-Level Chemistry and allow chemists to determine unknown concentrations, volumes, or reacting quantities using data from acid–base titrations. Understanding how to interpret experimental titration results, apply stoichiometry and use balanced equations is essential for accurate analytical work.

Understanding Titration Calculations

Titration calculations rely on quantitative relationships between reacting species, using measured volumes and known concentrations to determine an unknown value. A titration involves a reaction between an acid and a base, where the reacting species are in known stoichiometric ratios. Students must be confident with molar relationships, concentration expressions and balanced chemical equations, as these underpin the steps required to interpret titration data correctly.

Before approaching any calculation, it is essential to understand the concept of neutralisation, the basis for acid–base titrations. Neutralisation is the reaction between H⁺(aq) and OH⁻(aq) to form H₂O(l), occurring in a 1:1 molar ratio for strong acids and strong alkalis.

Neutralisation: The reaction of H⁺(aq) ions with OH⁻(aq) ions to form H₂O(l).

Titration calculations always begin by identifying the reacting species and their stoichiometric relationship, which must be taken from a correctly balanced chemical equation. Without this, subsequent mole calculations may be incorrect.

Key Concepts in Titration Calculations

A titration calculation typically involves the concentration expression, which links volume, concentration and amount of substance. This relationship is central to calculating either an unknown concentration or an unknown reacting volume.

Concentration: The amount of solute in mol per dm³ of solution (mol dm⁻³).

After applying the concentration expression, the next conceptual step is recognising the role of the mole ratio, derived from the balanced equation. This ratio indicates how many moles of one species react with another and must always be applied before solving for the unknown value.

Normal calculation processes rely on using accurate units. Volumes must be converted into dm³ when using concentration in mol dm⁻³, ensuring consistent units throughout.

Concentration Formula (c) = n ÷ V

c = concentration (mol dm⁻³)

n = amount of substance (mol)

V = volume of solution (dm³)

This equation is central to all titration calculations, but students must also apply stoichiometric reasoning. The mole ratio acts as the bridge between known and unknown quantities.

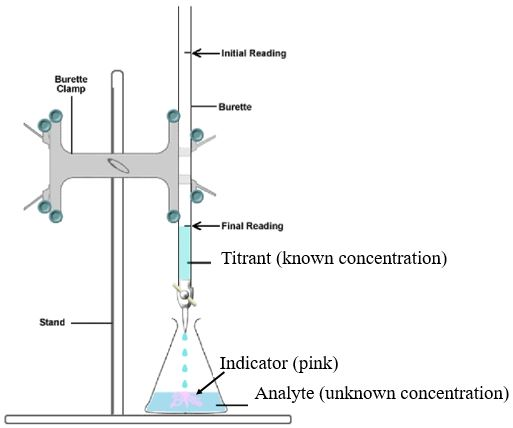

A typical titration involves gradually adding one solution from a burette into a conical flask containing a measured volume of another solution until a clear endpoint is reached.

Generic apparatus for an acid–base titration. The burette delivers a known concentration titrant into the analyte with an indicator present, illustrating how titre volumes are obtained for calculations. Source

Burette readings should be taken with your eye level to the meniscus and recorded to two decimal places to ensure reliable volume data for titration calculations.

Close-up of a burette scale showing the meniscus against the graduations, illustrating precise titre readings used before carrying out concentration and stoichiometry calculations. Source

For many acid–base titrations, the endpoint used in calculations is taken as the first permanent colour change of an indicator such as phenolphthalein.

Beaker containing a solution with the faint pink colour of phenolphthalein in alkali, illustrating the endpoint that provides the titre for titration calculations. Source

Structured Approach to Titration Calculations

Although titration problems may be described in different ways, the underlying method follows a consistent sequence. Understanding this structure helps students tackle both familiar and unfamiliar titration scenarios with confidence.

Essential Steps in Titration Calculations

Identify the balanced chemical equation.

Extract the stoichiometric mole ratio of acid to base.

Record the known information.

Include concentrations, volumes and any given ionic charges where relevant.

Convert all volumes into dm³.

This ensures compatibility with mol dm⁻³ concentration units.

Calculate the number of moles of the known solution using the concentration formula.

Use the mole ratio to determine the number of moles of the unknown solution.

Convert moles into the required final quantity, usually concentration or volume, using the same equation rearranged appropriately.

These structured steps remain consistent whether dealing with monoprotic acids, diprotic acids, or bases with varying ionic charges.

Unstructured Titration Calculations

Unstructured titration problems often require students to recognise missing pieces of information themselves. These questions may include unfamiliar acids or bases, but the calculation method always returns to stoichiometric principles. Recognising species charges and the balancing of ionic equations may be essential when identifying the correct mole relationship.

To succeed, students must evaluate the problem thoroughly before attempting calculations. This involves analysing what has been measured experimentally, determining what must be found, and applying the titration steps in a flexible but logically consistent order.

Skills Required for Unstructured Calculations

Interpretation of experimental context, including unusual acid or base compositions.

Recognition of the relevant reaction type, ensuring correct identification of reacting ions.

Establishing the correct stoichiometric ratio, even if full equations are not explicitly provided.

Fluent use of concentration, volume and mole relationships, applied adaptively to unfamiliar data.

Conversion of units, especially when results are provided in cm³ rather than dm³.

Importance of Stoichiometry in Titrations

Stoichiometry is fundamental to all titration calculations because acids and bases may not always react in a simple 1:1 ratio. Understanding ionic charges and species structure enables students to derive correct mole relationships. For example, a diprotic acid supplies two moles of H⁺ per mole of acid, altering the required volume or concentration for neutralisation. Recognising such cases ensures accurate quantitative interpretation.

In all titration contexts, success depends on translating experimental measurements into chemical amounts through correct application of mole relationships. This firm grasp of stoichiometry allows accurate calculation of unknown concentrations, even when dealing with unfamiliar titration systems.

Below is the corrected version using proper bullet points.

FAQ

The choice of indicator depends on the pH range over which the titration’s equivalence point occurs.

For strong acid–strong base titrations, most indicators with a mid-range transition are suitable.

For weak acid–strong base or weak base–strong acid titrations, choose an indicator whose transition range overlaps the steep section of the titration curve.

Suitable indicators include:

Phenolphthalein for weak acid–strong base

Methyl orange for strong acid–weak base

Errors can emerge from measurement inaccuracies, concentration changes, or equipment handling.

Common issues include:

Misreading the burette due to parallax

Using wet glassware that dilutes solutions

Air bubbles in the burette tap

Incorrectly judging the endpoint colour

To minimise these, ensure consistent eye-level readings, rinse apparatus correctly, remove air bubbles before starting, and add titrant dropwise near the endpoint.

Concordant titres improve reliability by confirming that repeated measurements align closely.

Titre values within 0.10 cm³ of each other indicate precise technique and stable endpoint detection.

Using an average of concordant titres reduces the influence of anomalies and enhances confidence in the calculated concentration.

Polyprotic acids release more than one proton per molecule, altering the stoichiometric relationship.

For a diprotic acid:

1 mole of acid provides 2 moles of H⁺

Twice as much alkali is required to neutralise a given amount of the acid compared with a monoprotic acid

This must be reflected in calculations, particularly when determining moles from titres and writing balanced equations.

A prepared solution may not have the exact concentration expected from theoretical mixing.

Standardisation involves titrating the solution against a primary standard to determine its precise concentration.

This ensures that subsequent titration calculations use accurate values, improving the validity of results derived from the solution.

Practice Questions

A student titrates 25.0 cm³ of sodium hydroxide solution with hydrochloric acid of known concentration.

The titre recorded is 23.45 cm³ of 0.100 mol dm⁻³ HCl.

Calculate the number of moles of HCl added during the titration. Show your working. (2 marks)

Correct use of n = c × V with volume converted to dm³ (0.02345 dm³). (1 mark)

Correct calculation: moles of HCl = 0.100 × 0.02345 = 0.002345 mol. (1 mark)

(5 marks)

A sample of a monoprotic organic acid, HA, is dissolved in water to make 250 cm³ of solution.

25.0 cm³ of this solution requires 18.60 cm³ of 0.150 mol dm⁻³ NaOH for complete neutralisation.

The equation for the reaction is:

HA + NaOH → NaA + H₂O

Using the titration data:

(a) Calculate the concentration of HA in mol dm⁻³. (3 marks)

(b) Calculate the total number of moles of HA in the original 250 cm³ solution. (2 marks)

(a)

Calculates moles of NaOH: 0.150 × 0.01860 = 0.00279 mol. (1 mark)

Correctly states 1:1 mole ratio of HA : NaOH from balanced equation. (1 mark)

Moles of HA in 25.0 cm³ = 0.00279 mol; concentration = 0.00279 ÷ 0.0250 = 0.1116 mol dm⁻³ (accept 0.112). (1 mark)

(b)

Correct scaling to full 250 cm³: multiply by 10. (1 mark)

Total moles of HA = 0.00279 × 10 = 0.0279 mol. (1 mark)