OCR Specification focus:

‘Define oxidation and reduction in terms of electron transfer and changes in oxidation number, with s-, p- and d-block examples.’

Redox in Terms of Electrons and Oxidation Numbers

Redox chemistry explains how electrons move between species and how oxidation numbers change. These concepts underpin reactions across the s-, p- and d-blocks.

Introduction (25 words):

Redox reactions involve simultaneous electron loss and gain. Understanding oxidation numbers and electron transfer provides a consistent framework for describing redox processes across the periodic table.

Oxidation and Reduction: Core Ideas

Redox processes always occur in pairs, meaning oxidation cannot happen without reduction. The two processes are directly linked by the movement of electrons and the corresponding changes in oxidation number.

Oxidation in Terms of Electron Transfer

Oxidation is defined by the loss of electrons from a species. When an atom or ion loses electrons, its oxidation number becomes more positive.

Oxidation: Loss of electrons by an atom, ion or molecule, increasing its oxidation number.

This definition focuses on electrons moving from one species to another in the course of a redox reaction.

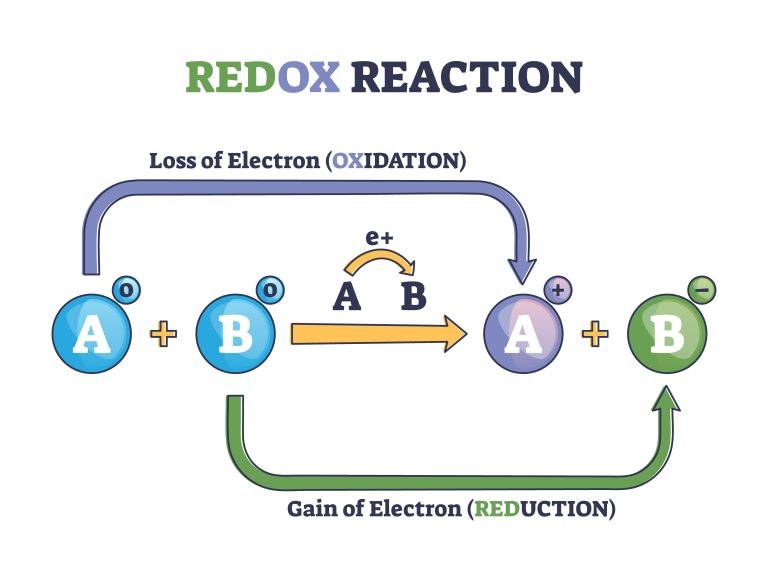

This diagram shows element A losing an electron to element B, illustrating oxidation and reduction as simultaneous processes within a redox reaction. Source

This relationship is particularly clear in s-block metals, which commonly lose electrons to form positively charged ions.

Reduction in Terms of Electron Transfer

Reduction describes the gain of electrons by a species. As electrons are added, the oxidation number becomes more negative.

Reduction: Gain of electrons by an atom, ion or molecule, decreasing its oxidation number.

This framework helps explain reactions involving p-block non-metals, which frequently gain electrons.

A sentence about how oxidation and reduction always occur together is essential, as the electron lost by one species must be gained by another.

Oxidation Numbers in Redox

Oxidation numbers provide a systematic method for identifying electron transfer, especially when electrons are not explicitly shown in an equation.

Definition of Oxidation Number

Oxidation numbers are assigned to atoms to indicate their relative degree of oxidation or reduction within a compound or ion.

Oxidation Number: A value assigned to an atom in a species representing its total number of electrons lost or gained relative to the neutral atom.

These values can be positive, negative or zero, depending on electron distribution.

A brief explanation between definitions helps emphasise why oxidation numbers are essential for redox analysis, particularly when dealing with complex ions or transition metals.

General Rules for Assigning Oxidation Numbers

To identify redox changes accurately, it is crucial to recall standard OCR rules:

Uncombined elements have oxidation number 0 (e.g. Zn, O₂).

Monatomic ions have oxidation numbers equal to their charge (e.g. Na⁺ = +1).

Oxygen is typically –2, except in peroxides (–1) or bonded to fluorine (+2).

Hydrogen is usually +1, except in metal hydrides (–1).

The sum of oxidation numbers equals the overall charge of the species.

In molecular compounds, the more electronegative element usually has the negative oxidation number.

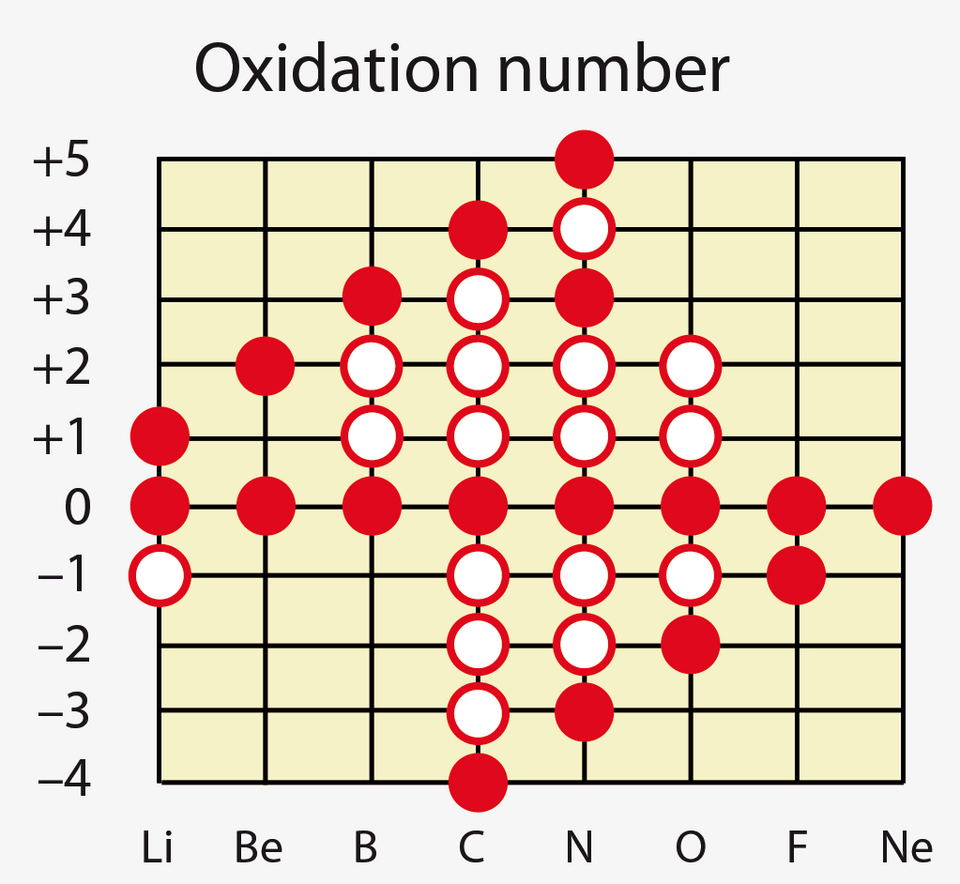

These typical oxidation numbers reflect how many electrons atoms of each element tend to gain, lose or share in compounds.

This chart shows common and less common oxidation numbers for Period 2 elements, illustrating how oxidation states vary across the period. Source

These rules allow consistent assignment across s-, p- and d-block examples.

Linking Electron Transfer and Oxidation Numbers

Redox reactions can be described in two complementary ways:

Electron transfer (actual movement of electrons).

Oxidation number changes (book-keeping method showing where electrons have effectively moved).

Identifying Oxidation and Reduction Through Oxidation Numbers

A species is oxidised if its oxidation number becomes more positive. A species is reduced if its oxidation number becomes more negative.

Oxidising Agent: A species that causes oxidation by accepting electrons; it is reduced in the process.

A sentence explaining the opposite behaviour of reducing agents reinforces the idea that redox processes are reciprocal.

Reducing Agent: A species that causes reduction by donating electrons; it is oxidised in the process.

These terms are frequently used when interpreting chemical equations.

Redox Across the Periodic Table

OCR requires understanding of redox behaviour in s-, p- and d-block elements, as their redox patterns differ.

s-Block Redox Patterns

Group 1 and 2 metals commonly undergo oxidation, forming +1 and +2 ions.

Electron loss is straightforward: outer electrons are easily removed.

Typical reactions include metal–water or metal–oxygen redox processes.

p-Block Redox Patterns

Non-metals often undergo reduction, gaining electrons to form anions.

Many p-block elements show multiple oxidation states, especially in the halogens and group 16 elements.

Oxidation number changes illustrate disproportionation and other characteristic behaviours.

d-Block Redox Patterns (Transition Metals)

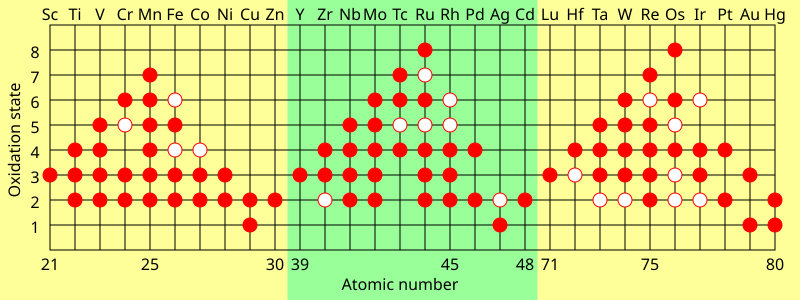

Transition metals show varied oxidation states due to their partially filled d-subshells. This leads to:

Multiple possible oxidation numbers for a single element.

Redox reactions that involve both electron transfer and ligand-related changes.

Formation of complex ions where oxidation states help determine metal charge and overall ion properties.

Transition metals in the d-block commonly show several oxidation states, such as +2 and +3 for iron or +2 and +4 for manganese.

This diagram summarises common and less common oxidation states of transition metals, supporting understanding of variable d-block redox behaviour. Source

These patterns make oxidation numbers especially valuable in analysing d-block chemistry, where electron transfer is less obvious.

Interpreting Redox Equations

Redox equations reveal oxidation-number changes even when electrons are not explicitly shown. Key steps include:

Identifying oxidation number changes for each element involved.

Determining which species loses or gains electrons.

Linking these changes to the roles of oxidising and reducing agents.

Verifying that oxidation and reduction occur simultaneously.

Bullet points make interpretation clearer, especially when reactions involve several species or when transition-metal ions are involved.

Redox chemistry in OCR A-Level requires students to apply both oxidation-number and electron-transfer reasoning, ensuring accurate interpretation across s-, p- and d-block reactions.

FAQ

Electron-transfer redox reactions show explicit movement of electrons, usually visible in half-equations. These are common for s-block metals, where electron loss is straightforward.

For reactions where electrons are not directly shown—such as covalent reactions or those involving transition metals—oxidation numbers offer a clearer way to identify oxidation and reduction.

Use oxidation-number changes when electron flow cannot be written simply or when multiple oxidation states are involved.

Oxidation numbers do not represent actual electron positions. They assume complete electron transfer even in covalent bonds.

This makes them an effective bookkeeping tool rather than a literal description.

They allow consistent identification of oxidation and reduction across ionic, covalent and coordinate compounds, regardless of real electron density.

Transition metals can access multiple oxidation states because of their partially filled d-subshells.

This leads to:

Overlapping energy levels that allow removal or gain of varying numbers of electrons

Formation of stable complex ions that influence oxidation state

Redox processes that may involve ligand changes as well as electron transfer

Disproportionation happens when the same element is both oxidised and reduced in one reaction.

This is more common when an element has several stable oxidation states.

Some p-block elements (e.g. chlorine, sulphur) and many transition metals possess oxidation states of similar stability, making both upward and downward changes feasible.

Assign oxidation numbers to each species before and after reaction.

Then identify which atoms increase or decrease in oxidation number.

This allows you to determine:

The species oxidised

The species reduced

Which reactant acts as the oxidising agent

Which reactant acts as the reducing agent

This method works even when the reagents are unfamiliar or when electrons cannot be written explicitly.

Practice Questions

State what is meant by:

(a) oxidation in terms of electron transfer

(b) reduction in terms of oxidation number.

(2 marks)

(a)

Oxidation is loss of electrons. (1)

(b)

Reduction is a decrease in oxidation number. (1)

A transition-metal compound contains iron that is oxidised during a redox process.

The oxidation number of iron increases from +2 in Fe2+ to +3 in Fe3+.

(a) Identify the species acting as the oxidising agent.

(b) Explain, with reference to electrons, why this species is the oxidising agent.

(c) Suggest why transition metals such as iron commonly take part in redox reactions involving multiple oxidation states.

(d) State what happens to the oxidation number of the species that is reduced in this reaction.

(5 marks)

(a)

The oxidising agent is the species that causes Fe2+ to be oxidised (accept suitable named species if provided). (1)

(b)

It accepts electrons from Fe2+. (1)

(c)

Transition metals have variable oxidation states due to partially filled d-subshells. (1)

This allows them to lose or gain different numbers of electrons in reactions. (1)

(d)

Its oxidation number becomes more negative (or decreases). (1)