OCR Specification focus:

‘Interpret redox equations, including unfamiliar examples, to predict oxidation-number changes and electron loss or gain.’

Understanding Redox Interpretation and Prediction

Redox reactions are essential in chemistry, involving the transfer of electrons between chemical species. To interpret and predict redox reactions, students must identify oxidation-number changes and determine which species are oxidised or reduced.

Redox (reduction–oxidation) processes underpin topics like electrochemistry, metal extraction, and combustion. This subsubtopic focuses on analysing equations, including unfamiliar ones, to recognise electron movement patterns and oxidation-number shifts.

Identifying Oxidation and Reduction

In a redox reaction, oxidation and reduction always occur together.

Oxidation: The loss of electrons or increase in oxidation number by an atom, ion, or molecule.

Reduction: The gain of electrons or decrease in oxidation number by an atom, ion, or molecule.

When interpreting an equation:

Determine oxidation numbers for all elements involved.

Identify which species’ oxidation number increases (oxidised) and which decreases (reduced).

Recognise that electrons are lost by the reducing agent and gained by the oxidising agent.

Assigning Oxidation Numbers

Accurate oxidation-number assignment is the foundation of interpreting redox reactions.

Use the established oxidation-number rules, including:

Elements in their uncombined state: 0 (e.g. O₂, N₂, Na).

Monoatomic ions: equal to their ionic charge.

Oxygen: –2 (except in peroxides, where it is –1).

Hydrogen: +1 (except in metal hydrides, where it is –1).

The algebraic sum of oxidation numbers in a neutral compound equals 0.

The algebraic sum in a polyatomic ion equals the ion’s charge.

These principles allow you to track changes during reactions systematically.

Step-by-Step Method for Interpreting Redox Reactions

To interpret or predict oxidation-number changes, follow this structured approach:

Write the balanced equation.

Ensure all atoms are balanced before analysing oxidation numbers.

Assign oxidation numbers to every element. Use the rules above to determine their values.

Identify the changes in oxidation numbers.

An increase indicates oxidation (loss of electrons).

A decrease indicates reduction (gain of electrons).

Determine oxidising and reducing agents.

The oxidising agent is reduced (gains electrons).

The reducing agent is oxidised (loses electrons).

Verify electron balance.

The total number of electrons lost = total number of electrons gained.

This approach ensures accurate identification of redox processes even in unfamiliar contexts.

Electron Transfer and Oxidation Numbers

Each redox reaction involves electron transfer.

The relationship between oxidation-number change and electron movement is direct:

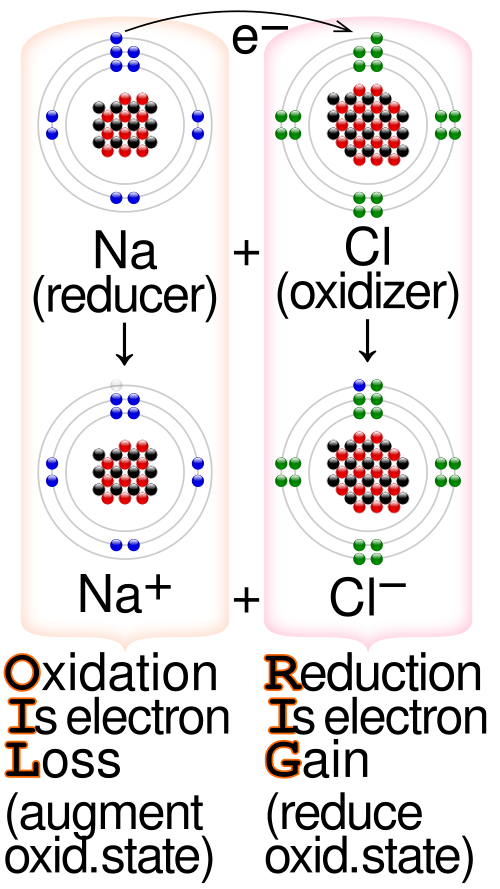

A simplified redox schematic illustrating electron transfer from a reducing agent to an oxidising agent. The diagram labels oxidation (electron loss) and reduction (electron gain), reinforcing the link between oxidation-number change and electron movement. It aligns with OCR expectations for identifying species that lose or gain electrons. Source

1 unit change in oxidation number corresponds to 1 electron transferred per atom.

Multiply by the number of atoms to find total electrons gained or lost.

This principle allows for balancing redox equations by electron count.

Predicting Redox Reactions

Prediction involves deducing which reactants can undergo oxidation or reduction based on their oxidation states and chemical reactivity.

When predicting:

Identify potential reducing agents (metals, ions, or species that readily lose electrons).

Identify potential oxidising agents (non-metals, oxygen, halogens, or species that readily gain electrons).

Compare standard oxidation numbers or known electrode potentials (in advanced contexts) to anticipate which direction electron flow will occur.

For example:

Transition metals often form multiple oxidation states, making them versatile in redox predictions.

Reactive metals (e.g. magnesium, zinc) are commonly oxidised.

Strong oxidisers (e.g. potassium permanganate, dichromate) often accept electrons.

Oxidation Numbers in Redox Equation Interpretation

Changes in oxidation numbers are the clearest indicators of redox behaviour.

When interpreting, focus on what changes and by how much.

For instance:

If an element’s oxidation number increases from +2 to +3, it has lost one electron per atom.

If it decreases from 0 to –2, it has gained two electrons per atom.

Such patterns help identify redox pairs, predict reaction feasibility, and write half-equations.

Writing Half-Equations

Half-equations explicitly show the electron transfer aspect of redox changes.

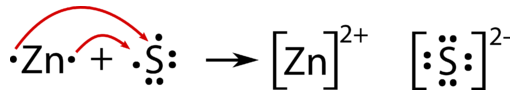

Lewis-dot arrows indicate electrons moving from Zn (oxidised to Zn²⁺) to S (reduced to S²⁻). This visual supports writing paired half-equations and linking them to oxidation-number changes. Note: The dot-structure style is an extra representational detail beyond the minimum OCR requirement. Source

Half-equation: A representation of either the oxidation or reduction process showing the movement of electrons.

When writing:

For oxidation, electrons appear on the right-hand side.

For reduction, electrons appear on the left-hand side.

Ensure:

Atoms are balanced first.

Charges are balanced by adding electrons.

If necessary, balance oxygen using H₂O and hydrogen using H⁺ (in acidic conditions).

Normal redox equations combine these two balanced half-equations, ensuring total electron transfer equality.

Common Patterns in Redox Interpretation

Students should recognise recurring redox patterns:

Metal displacement reactions: A more reactive metal displaces a less reactive one from a compound.

Zinc reduces Cu²⁺ to Cu(s) while zinc itself is oxidised to Zn²⁺. The deposited reddish copper on the zinc surface provides visible evidence of electron transfer. This directly exemplifies oxidation-number increase for zinc and decrease for copper ions. Source

Combustion reactions: Elements combine with oxygen; oxidation of the fuel occurs.

Disproportionation reactions: A single element is simultaneously oxidised and reduced.

Decomposition reactions: Compounds break down with oxidation-number changes, often involving oxygen evolution or reduction.

Understanding these enables quick interpretation of unfamiliar examples.

Electron Bookkeeping and Conservation

All redox processes obey the law of conservation of charge and matter.

Thus:

The total number of electrons lost equals the number of electrons gained.

The overall equation must remain electrically neutral.

This ensures that every correctly interpreted redox equation maintains charge balance across the system.

Summary of Key Points for Prediction

To predict redox changes in any equation:

Identify elements with variable oxidation states.

Track numerical changes in oxidation numbers.

Associate increases and decreases with oxidation and reduction respectively.

Recognise the roles of oxidising and reducing agents.

Verify electron balance to confirm a valid redox relationship.

Through consistent application of these principles, OCR A-Level Chemistry students can confidently interpret and predict redox reactions in both familiar and novel contexts.

FAQ

A redox equation specifically tracks the transfer of electrons and the associated changes in oxidation numbers for elements involved.

A simple chemical equation may only show reactants and products balanced by atoms and charges.

In redox equations:

The oxidation number of one species increases (oxidation).

The oxidation number of another decreases (reduction).

Electrons lost and gained are balanced across half-equations to maintain overall charge neutrality.

Roman numerals indicate the oxidation state of elements that can exist in multiple oxidation states, especially transition metals.

For example:

Iron(II) oxide contains Fe²⁺ ions.

Iron(III) oxide contains Fe³⁺ ions.

These numerals help identify which specific ion is present in a compound and are essential for interpreting and predicting redox behaviour accurately.

A disproportionation reaction occurs when the same element is both oxidised and reduced within a single reaction.

To identify one:

Assign oxidation numbers to all atoms of that element in reactants and products.

If the element’s oxidation number increases in one product and decreases in another, disproportionation has occurred.

Common examples involve chlorine, hydrogen peroxide, and nitrogen oxides.

Spectator ions do not undergo any oxidation or reduction; they remain chemically unchanged throughout the reaction.

When writing ionic or half-equations:

Spectator ions are omitted to simplify the equation.

The focus remains solely on species that gain or lose electrons.

This makes it easier to analyse oxidation-number changes and identify oxidising and reducing agents.

Redox reactions underpin many large-scale chemical and natural systems. Examples include:

Metal extraction and refining (e.g. extraction of iron from haematite using carbon monoxide).

Energy generation in batteries and fuel cells through controlled electron transfer.

Corrosion and rust prevention, where oxidation is managed or inhibited.

Wastewater treatment and environmental remediation, using oxidising agents to neutralise contaminants.

Their control and understanding are essential for both technological applications and environmental protection.

Practice Questions

In the reaction between iron(III) oxide and carbon monoxide:

Fe₂O₃ + 3CO → 2Fe + 3CO₂

Identify which species is oxidised and which is reduced.

Explain your reasoning in terms of changes in oxidation number.

(2 marks)

1 mark for identifying that carbon monoxide (CO) is oxidised to carbon dioxide (CO₂).

1 mark for identifying that iron(III) oxide (Fe₂O₃) is reduced to iron (Fe).

(Allow reasoning such as: oxidation number of carbon increases from +2 to +4; oxidation number of iron decreases from +3 to 0.)

Chlorine gas can react with cold, dilute sodium hydroxide to form sodium chloride and sodium chlorate(I):

Cl₂ + 2NaOH → NaCl + NaClO + H₂O

(a) Assign oxidation numbers to the chlorine atoms in Cl₂, NaCl, and NaClO. (2 marks)

(b) Explain why this reaction is described as a disproportionation reaction, using your oxidation numbers to justify your answer. (3 marks)

(5 marks)

(a)

1 mark for chlorine in Cl₂ = 0.

1 mark for chlorine in NaCl = –1 and in NaClO = +1.

(b)

1 mark for recognising that one element (chlorine) is both oxidised and reduced.

1 mark for stating chlorine in Cl₂ is oxidised from 0 to +1 (in NaClO).

1 mark for stating chlorine in Cl₂ is reduced from 0 to –1 (in NaCl).

(Allow full marks for a clear statement that chlorine undergoes both oxidation and reduction, referencing the changes in oxidation number.)