OCR Specification focus:

‘Apply rules to assign and calculate oxidation numbers for atoms in elements, compounds and ions, including O in peroxides and H in metal hydrides.’

Understanding oxidation numbers is essential for analysing redox reactions. This section outlines the systematic rules used to assign oxidation numbers across elements, compounds and ions in chemical formulae.

Assigning Oxidation Numbers

Oxidation numbers are bookkeeping values used to track electron distribution in atoms during chemical reactions. They allow chemists to identify oxidation and reduction processes clearly and consistently, supporting the interpretation of complex reactions.

Fundamental Purpose

Oxidation numbers reflect the hypothetical charge an atom would have if bonding were entirely ionic. They are not always true charges but serve as a formalism to interpret electron movement. Assigning these numbers requires applying consistent rules across different chemical species.

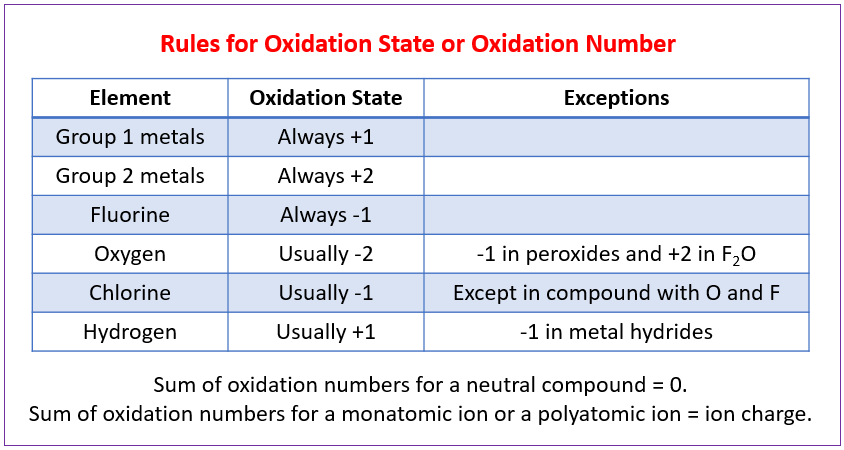

General Rules for Oxidation Numbers

When determining oxidation numbers, chemists follow a set of established conventions. These rules must be applied in order and adapted to the species under consideration.

Atoms in their elemental form always have an oxidation number of 0.

Simple ions have oxidation numbers equal to their ionic charge.

In compounds and complex ions, oxidation numbers are assigned based on electronegativity and established common oxidation states.

The sum of oxidation numbers equals zero for neutral compounds and equals the overall charge for polyatomic ions.

Oxygen typically has an oxidation number of –2, except in peroxides where it is –1, and in compounds with fluorine, where it may be positive.

Hydrogen usually has an oxidation number of +1, except in metal hydrides, where it is –1.

Group 1 metals are always +1, and Group 2 metals are always +2 in compounds.

Key Terms

The concept of oxidation number connects directly to ideas of electron distribution.

Oxidation number: The assigned value representing the theoretical electron gain or loss of an atom assuming completely ionic bonding.

Assigning oxidation numbers correctly builds confidence in analysing unfamiliar reactions, especially when identifying which species undergo oxidation or reduction.

Oxidation Numbers in Elements

Atoms in their standard states—including diatomic molecules such as O₂, H₂ and Cl₂—are always assigned oxidation numbers of 0. This rule also applies to allotropes such as graphite, diamond and phosphorus forms. Recognising this is crucial because elemental species often participate as reactants or products in redox processes.

Oxidation Numbers in Ions

For monatomic ions, the oxidation number is simply the numerical charge on the ion.

Monatomic ion: An ion consisting of a single atom carrying a positive or negative electric charge.

This helps make oxidation states very straightforward for ions such as Na⁺, Cl⁻, Mg²⁺, or O²⁻, which appear frequently in reaction equations.

Before applying more complex rules, ensure ionic charges are correctly identified, as they set the foundation for interpreting ionic and redox behaviour.

Oxidation Numbers in Molecules and Compounds

To assign oxidation numbers in compounds, chemists apply electronegativity trends and established oxidation state patterns.

Key points include:

The most electronegative element in a compound is usually assigned its typical negative oxidation state.

In binary compounds, the element with higher electronegativity is assigned the negative value.

Oxidation numbers must be consistent with the overall chemical formula when summed.

This systematic approach enables accurate interpretation of covalent and ionic structures in a wide range of substances.

Special Cases: Oxygen

Oxygen most commonly has an oxidation number of –2, but important exceptions must be memorised for OCR Chemistry.

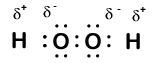

Peroxides (e.g., H₂O₂): Oxygen has an oxidation number of –1.

Compounds with fluorine: Oxygen adopts a positive oxidation number due to fluorine’s greater electronegativity.

Superoxides: Oxygen may have fractional oxidation states, though these are less common at A-Level.

Peroxide: A compound containing an O–O single bond in which each oxygen atom has an oxidation number of –1.

In peroxides, such as H₂O₂, each oxygen has an oxidation number of –1 because the O–O bond changes how the shared electrons are allocated.

Electron‑dot structure of hydrogen peroxide showing shared electron pairs and the O–O bond, illustrating why each oxygen has an oxidation number of –1 in peroxides. Source

Special Cases: Hydrogen

Hydrogen also has variable oxidation numbers depending on the bonding partner.

With non-metals, hydrogen is almost always +1.

With metals, hydrogen becomes –1, forming metal hydrides.

Metal hydride: A compound in which hydrogen is bonded to a metal and has an oxidation number of –1.

This distinction is essential when analysing redox behaviour in inorganic compounds.

After identifying special cases, the oxidation numbers assigned should always be checked by summing to the overall charge of the species to confirm accuracy.

Oxidation Numbers in Polyatomic Ions

Oxidation numbers also apply to species containing multiple atoms with an overall charge. To assign oxidation numbers in polyatomic ions:

Identify the total charge of the ion.

Assign oxidation numbers to elements with known, consistent states.

Solve for the remaining unknown oxidation numbers algebraically.

Verify the sum equals the ion’s overall charge.

Common ions where this method is necessary include sulfate, nitrate, carbonate and phosphate. These appear frequently in redox contexts where correct oxidation number assignment ensures proper classification of electron-transfer processes.

Oxidation Numbers and Redox Identification

Although full redox analysis belongs to later sections, the ability to assign oxidation numbers underpins redox chemistry. Increasing oxidation number indicates oxidation (electron loss), while decreasing oxidation number indicates reduction (electron gain). Accurate oxidation number work ensures correct interpretation of complex chemical equations.

Once you know the core rules for elements, ions, oxygen, hydrogen and the overall sum of oxidation numbers, you can systematically assign oxidation numbers to any element in a compound or ion.

Summary table of oxidation state rules, showing typical oxidation numbers and key exceptions such as oxygen in peroxides and hydrogen in metal hydrides. Source

FAQ

Oxidation numbers assume completely ionic bonding, while formal charges allocate electrons based on equal sharing within covalent bonds.

This means oxidation numbers track electron transfer in redox chemistry, whereas formal charges help assess stability and resonance structures.

In covalent molecules, the formal charge may be zero even when the oxidation number is significantly positive or negative.

Elements can exceed their common oxidation states when they bond with very electronegative atoms or form structures enabling electron withdrawal or donation.

This occurs especially with non-metals, which can share or donate multiple electrons through multiple bonding or expanded valence shells.

Chlorine, sulphur and nitrogen frequently show extended oxidation-state ranges due to these bonding possibilities.

Fractional oxidation states arise when electrons are delocalised across several identical atoms, making the oxidation state an average rather than a whole number.

This commonly occurs in:

superoxides

mixed-valence compounds

extended solids where electron density is shared

Students should note that fractional values do not represent real charges on individual atoms.

Electronegativity determines which atom in a bond is considered to “own” the shared electrons.

The more electronegative atom is assigned the negative oxidation number because it attracts electrons more strongly.

This is especially important in molecules with mixed non-metals where oxidation numbers cannot be predicted solely from common oxidation states.

They contain unusual bonding arrangements that shift how electrons are assigned.

In peroxides:

oxygen forms O–O bonds

neither oxygen fully attracts the shared electron pair

each oxygen is assigned –1 instead of –2

In metal hydrides:

hydrogen bonds to an electropositive metal

hydrogen is assigned –1 because it attracts electrons more strongly than the metal

Practice Questions

State the oxidation number of oxygen in each of the following and explain your answers briefly.

(a) Magnesium oxide, MgO

(b) Sodium peroxide, Na2O2

(2 marks)

(a) Oxygen in MgO has oxidation number –2.

Correct oxidation number (–2) = 1 mark

Reason given (oxygen is usually –2 in metal oxides) = 1 mark

(b) Oxygen in Na2O2 has oxidation number –1.

Correct oxidation number (–1) = 1 mark

Reason given (oxygen is –1 in peroxides due to the O–O bond) = 1 mark

Maximum 2 marks.

Chlorine forms several compounds with oxygen, including Cl2O, ClO2 and Cl2O7.

(a) Assign the oxidation number of chlorine in each of these compounds.

(b) Explain the steps and rules used to determine these oxidation numbers, making reference to electronegativity and the typical oxidation number of oxygen.

(c) State which compound contains chlorine in its highest oxidation state and justify your answer.

(5 marks)

(a)

Cl2O: chlorine is +1

ClO2: chlorine is +4

Cl2O7: chlorine is +7

(1 mark for each correct value, maximum 3 marks)

(b) Explanation of rules used:

States oxygen is usually –2 in compounds = 1 mark

Mentions electronegativity or assigning oxygen first due to higher electronegativity = 1 mark

(c)

Identifies Cl2O7 as containing chlorine in its highest oxidation state = 1 mark

Justification: chlorine has oxidation number +7, the highest possible for chlorine = 1 mark

Maximum 5 marks.