OCR Specification focus:

‘Carbonate ions react with aqueous acid to form carbon dioxide gas; observations and confirmatory tests are recorded.’

Testing for carbonate ions is a fundamental qualitative analysis technique that relies on detecting carbon dioxide gas produced during acid–carbonate reactions using simple, observable laboratory procedures.

Test for Carbonate Ions

The test for carbonate ions is an essential analytical procedure in OCR A-Level Chemistry, helping students identify carbonate (CO₃²⁻) compounds through characteristic gas formation. This test is emphasised in the specification as a required practical observation, focusing on visible reactions and confirmatory gas testing. Carbonates are common in salts, rocks, antacid formulations, water-treatment residues, and environmental samples, making understanding the test valuable across chemical contexts.

Principle of the Carbonate Test

When a carbonate reacts with a suitable acid, carbon dioxide gas is produced. This forms the foundation of the qualitative test and is linked directly to the specification requirement.

Carbonate ion: An anion with the formula CO₃²⁻ formed from carbonic acid and commonly found in metal carbonate salts.

The detection of carbon dioxide relies on both observing effervescence and confirming the identity of the gas using a secondary test.

Required Reagents and Apparatus

A standard laboratory setup is sufficient for carrying out the carbonate test. Students should ensure controlled handling of acids and appropriate collection of gas for confirmation.

Reagents:

Aqueous acid, typically dilute hydrochloric acid (HCl) or dilute nitric acid (HNO₃)

The solid or aqueous sample suspected to contain carbonate ions

Limewater (aqueous calcium hydroxide) for gas confirmation

Apparatus:

Test tubes

Dropping pipette

Delivery tube and bung (if gas transfer is required)

Protective equipment such as eye protection and laboratory coat

Step-by-Step Procedure

Following the correct sequence and observing the sample carefully are crucial for accurate identification. Students should record all visible changes as part of good analytical practice.

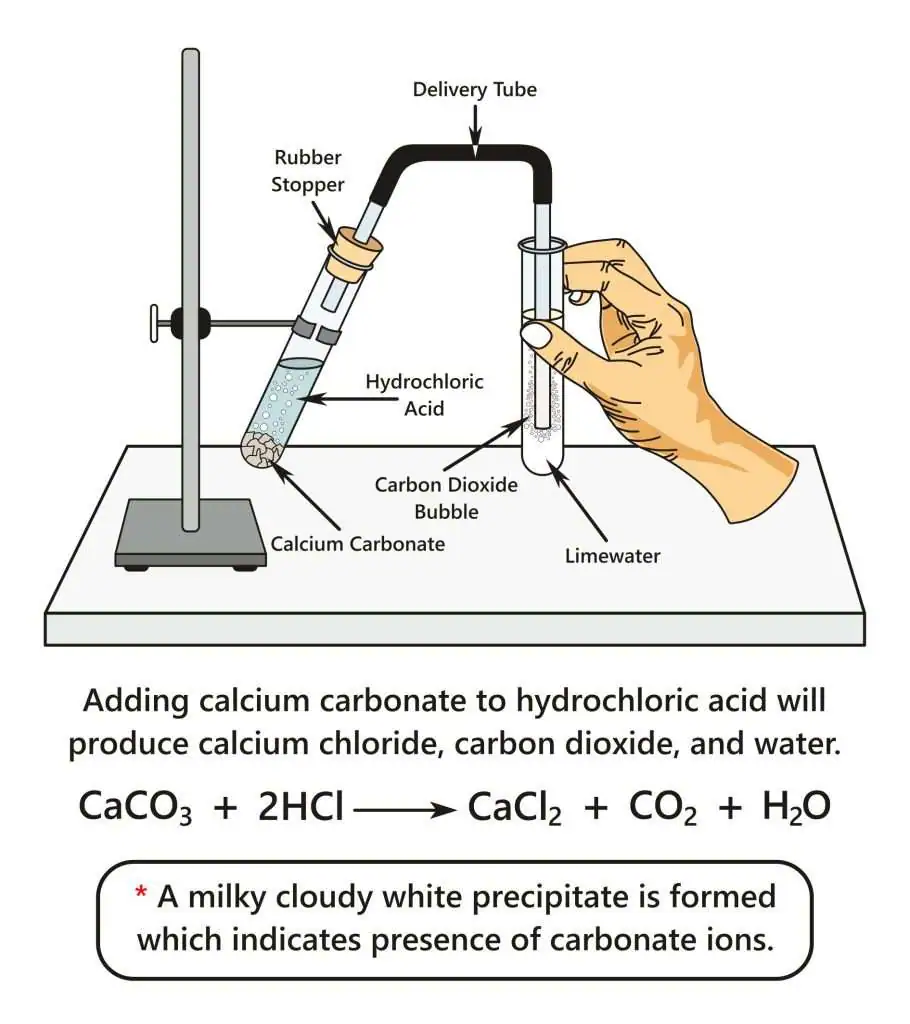

Apparatus for testing for carbonate ions using acid and limewater, illustrating CO₂ production and confirmatory precipitation in limewater. Includes the reaction equation, which exceeds minimal syllabus requirements but reinforces key chemistry concepts. Source

Testing for Carbonates:

Add a small volume of the sample to a clean test tube.

Introduce a few drops of dilute acid using a pipette.

Observe immediate changes such as fizzing or gas production.

If gas is produced, channel it using a delivery tube into limewater to confirm its identity.

Observations and Expected Results

Carbonate identification is based on two sequential observable features:

Primary Observation:

Effervescence occurs as carbon dioxide gas forms rapidly upon acid addition.

Solid carbonates may partially dissolve as the reaction proceeds.

The reaction is typically vigorous for more reactive metal carbonates such as those of Group 2 metals.

Confirmatory Observation:

When the gas is passed into limewater, the solution turns milky due to the formation of calcium carbonate.

This two-step process aligns with OCR expectations: observable gas evolution followed by a confirmatory test.

Chemistry of the Reaction

Understanding the chemical basis for observations strengthens conceptual recall and supports application in unknown-sample analysis.

Limewater: A saturated aqueous solution of calcium hydroxide, Ca(OH)₂(aq), used to test for carbon dioxide gas.

The reaction between carbonate ions and acid generates carbon dioxide, water, and a corresponding metal salt.

Acid–Carbonate Reaction (CO₃²⁻) = Acid + Metal Carbonate → Salt + Water + Carbon Dioxide

CO₃²⁻ = Carbonate ion; gaseous CO₂ forms the visible effervescence

A brief understanding of why limewater turns milky is also useful. Passing CO₂ through limewater leads to precipitation of insoluble calcium carbonate, creating the characteristic cloudy appearance.

Limewater Confirmation Explained

The limewater test is the universally accepted confirmatory method for carbon dioxide gas in school-level chemistry.

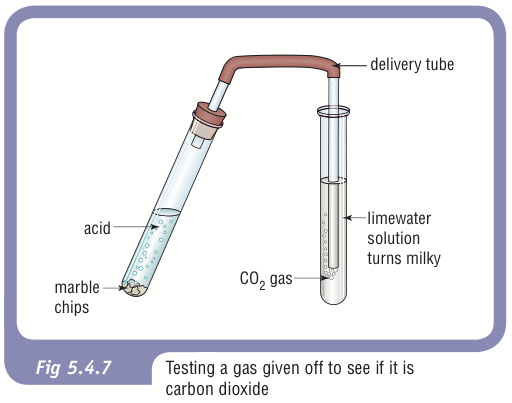

Diagram of CO₂ being bubbled through limewater, producing a milky suspension of calcium carbonate. The image includes surrounding context about acid–carbonate reactions not required by the specification, but the limewater test itself directly supports OCR learning outcomes. Source

Key points:

CO₂ reacts with aqueous Ca(OH)₂ to form a fine, white suspension of CaCO₃.

Continued bubbling eventually re-dissolves the precipitate as soluble calcium hydrogen carbonate forms.

Only the initial formation of the milky precipitate is used for confirmation in OCR qualitative analysis.

Practical Considerations and Limitations

The carbonate test is reliable, but correct technique is vital:

Do not confuse effervescence with reactions that produce other gases (e.g., H₂ from metals). Confirmation with limewater is essential.

Ensure acids used are not too concentrated, as vigorous reactions can cause splashing or loss of gas before testing.

Some hydrogencarbonates (HCO₃⁻) also produce CO₂ with acids; OCR expects students to recognise that the test does not distinguish between carbonates and hydrogencarbonates.

Samples containing mixtures of anions may require the carbonate test to be performed before sulfate or halide tests to avoid formation of insoluble precipitates that interfere with other analyses.

Typical Errors to Avoid

Students should be aware of common pitfalls:

Holding limewater too far from the reaction vessel, preventing sufficient gas transfer.

Misinterpreting weak effervescence in samples with low carbonate concentration.

Adding excessive solid sample, which may cause splashing when acid is introduced.

Good practice includes running a control test with a known carbonate to compare reaction vigour, although this is not required by the OCR specification.

Recording Observations

Accurate and unambiguous observations are essential for qualitative analysis:

Describe effervescence clearly (e.g., “rapid bubbling observed”).

Note the limewater change precisely (“limewater turned milky”).

Avoid speculative language and do not infer reaction equations in observation tables.

These practices support high-quality data recording expected in A-Level Chemistry practical work.

Understood — here are the corrected versions using proper bullet points (hyphens only), keeping everything else the same.

FAQ

Dilute acid is used to control the rate of carbon dioxide release. Concentrated acids can cause violent reactions, leading to gas loss and inaccurate observations.

Using dilute acid also prevents secondary side reactions or decomposition, ensuring the gas produced originates solely from the carbonate–acid reaction.

Some carbonates produce gases upon heating, which may be confused with carbon dioxide. To confirm the presence of CO2, the evolved gas should still be passed into limewater.

If limewater turns milky, the gas is confirmed as carbon dioxide, regardless of whether it originated from heat or acid.

Limewater provides a simple, rapid visual change due to the formation of insoluble calcium carbonate. This makes it reliable even at low CO2 concentrations.

Other reagents, such as pH indicators or metal hydroxide solutions, may react more slowly or require additional interpretation.

Several variables can reduce reliability:

Using old or contaminated limewater, which may already appear cloudy

Gas escaping before reaching the limewater

Excessive solid carbonate causing splashing when acid is added

Strong airflow or draughts dispersing the gas

Careful control of apparatus positioning improves accuracy.

Yes, but interpretations must be made cautiously. Mixtures containing carbonates will still release CO2 upon acid addition.

However, insoluble solids or substances that also react with acids may obscure observations, so confirmatory testing with limewater is essential.

Practice Questions

A student adds dilute hydrochloric acid to a solid sample suspected to contain carbonate ions.

(a) State the visible observation that would indicate the presence of carbonate ions.

(b) Describe a confirmatory test to prove that the gas produced is carbon dioxide.

(2 marks)

(a)

Effervescence / fizzing / bubbling observed – 1 mark

(b)

Bubble the gas through limewater – 1 mark

Limewater turns milky / cloudy, confirming carbon dioxide (credit as part of the same mark)

A mixture of two unknown white solids is tested to determine whether carbonate ions are present.

The student adds dilute nitric acid to the mixture and observes vigorous effervescence.

The gas produced is passed into limewater, which turns milky.

(a) Write the ionic equation for the reaction between carbonate ions and an acid.

(b) Explain why the limewater turns milky.

(c) Suggest why this test must be carried out before adding barium ions to test for sulfate ions.

(d) Hydrogencarbonate ions also produce carbon dioxide with acids. Explain why the acid test alone cannot distinguish between carbonate and hydrogencarbonate ions.

(5 marks)

(a)

CO3^2– + 2H+ → CO2 + H2O – 1 mark

(Allow correctly balanced full ionic or full balanced chemical equation.)

(b)

Formation of insoluble calcium carbonate when CO2 reacts with calcium hydroxide in limewater – 1 mark

(c)

Carbonate ions would form insoluble barium carbonate, producing a white precipitate that interferes with the sulfate test – 1 mark

(d)

Both carbonate and hydrogencarbonate ions release CO2 with acids, so they give identical observations – 1 mark

One additional mark for clear explanation phrasing or fully correct chemical reasoning in any part above, up to the maximum.