OCR Specification focus:

‘Use measurements of mass change, gas volume, or time to investigate reaction rates, with appropriate practical techniques and data handling.’

Measuring reaction rates experimentally allows chemists to monitor how quickly reactants are used or products form. Reliable methods require accurate measurements, controlled variables, and clear links between observable changes and reaction progress.

Measuring Rates: Core Principles

Understanding reaction rates involves tracking a measurable physical change that occurs as a reaction proceeds. Rate is typically determined by assessing how a chosen variable changes with time, enabling the construction of graphs or comparison of rates under different conditions.

A reaction rate is the change in concentration of a reactant or product per unit time.

Reaction Rate: The change in concentration of reactant or product per unit time.

Reliable measurement depends on selecting a suitable technique aligned with the reaction’s behaviour, ensuring the change can be recorded with sufficient precision and frequency.

Choosing Appropriate Techniques

Reactions must produce an observable change that correlates consistently with the progress of the reaction. Three key experimental approaches emphasised by the OCR specification are:

Measuring mass change

Measuring gas volume produced

Measuring time taken for a visible event

These are supported by appropriate procedural choices, careful data collection, and awareness of limitations.

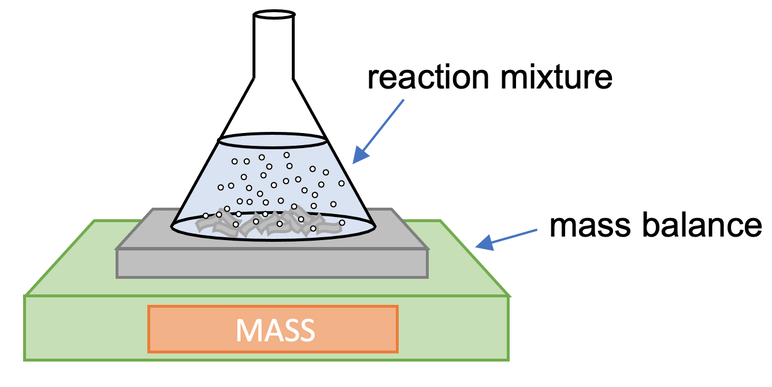

Mass Change Techniques

Monitoring Loss of Mass

This technique is especially valuable when gaseous products escape during the reaction. The reaction mixture is placed on a balance, and the mass is recorded at regular intervals.

Key considerations include:

Use of a top-pan balance with high precision

Ensuring the container allows gases to escape without significant evaporation of liquids

Minimising drafts and vibrations that destabilise readings

Recording mass at consistent time intervals to generate reliable rate curves

Mass loss is directly proportional to the quantity of gaseous product formed, assuming no other mass changes occur.

Diagram showing a conical flask on a digital balance, with gas bubbles forming and escaping as the reaction proceeds, allowing mass–time data to be used to determine reaction rate. Source

Suitable Reaction Types

Decomposition producing CO₂

Acid–carbonate reactions

Metal–acid reactions evolving H₂

These reactions generate data that can be plotted as mass vs time, where steeper gradients indicate faster rates.

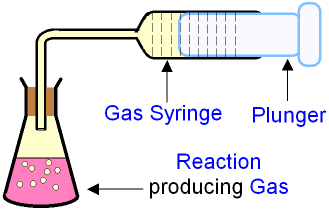

Gas Volume Techniques

Collecting Gas Volumes

Where gaseous products are produced, gas collection provides a clear and continuous measure of reaction progress. Common apparatus setups include a gas syringe or upturned measuring cylinder in a water trough.

Advantages of gas syringes:

High accuracy, typically ±0.5 cm³

Suitable for most gases unless highly soluble in water

Advantages of water trough collection:

Simple and inexpensive

Useful for insoluble gases such as hydrogen

Procedural Notes

Ensure airtight connections to prevent gas leakage

Use clamps to secure syringes or cylinders

Record gas volume frequently at the start when rate is highest

Maintain constant temperature to avoid gas expansion errors

Volume-time graphs can be used to estimate initial rates from early gradients.

Diagram showing a conical flask connected to a gas syringe used to collect gaseous product. The syringe scale allows volume measurements at timed intervals, supporting rate calculations. Source

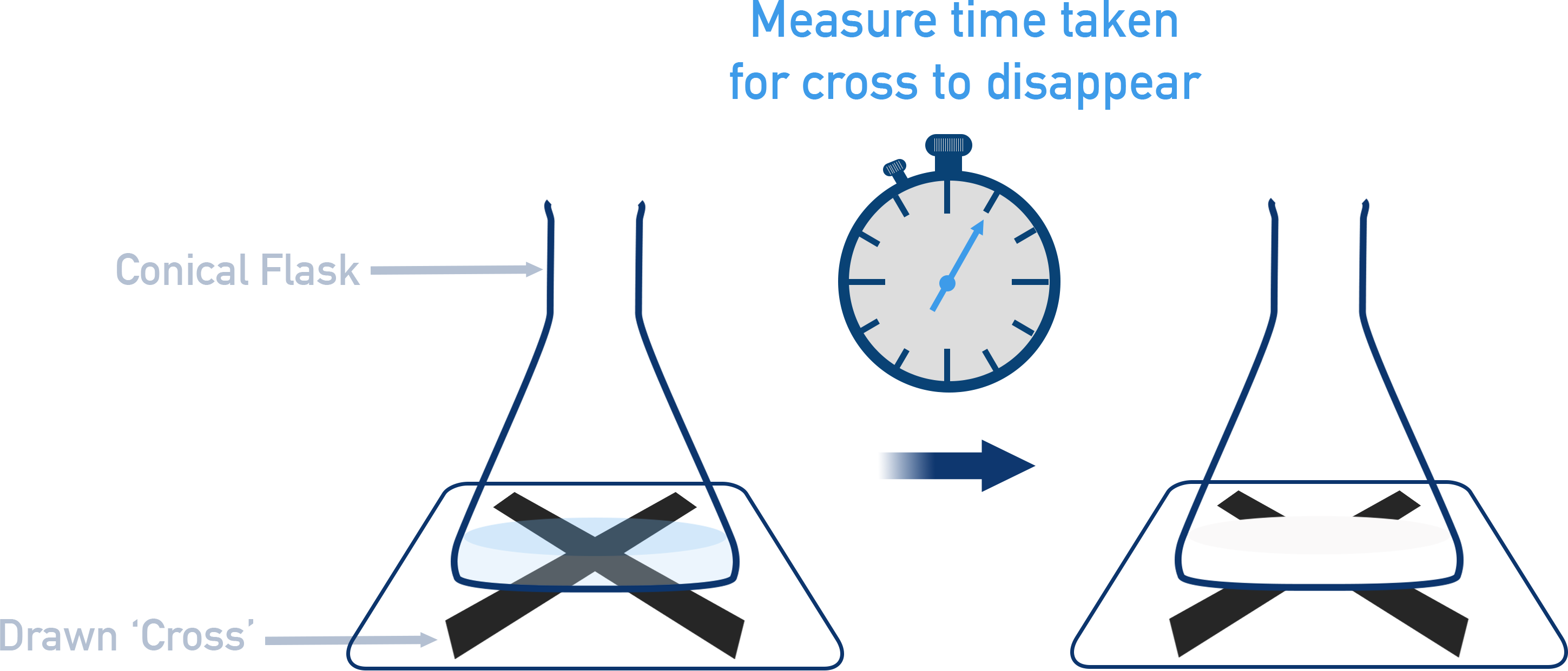

Time-Based Methods

Measuring Time for Visible Change

Some reactions produce a qualitative change that occurs at a reproducible point in the reaction. Monitoring time taken allows rate comparisons under different conditions.

Common examples include:

Appearance of a precipitate causing a cross beneath a flask to disappear

Colour changes due to reaction progress

Disappearance of a coloured reactant

These methods indirectly measure rate but offer practical value when other variables cannot be quantified easily.

Schematic of the disappearing cross experiment in which sulfur precipitate gradually obscures a cross, allowing the time for a visible change to be measured as an indicator of reaction rate. Source

Reliability Considerations

Human judgement introduces variability

Use consistent viewing angles

Ensure uniform lighting conditions

Repeat measurements and average times for improved accuracy

Such techniques allow comparison of how concentration, temperature or catalyst presence influences reaction speed.

Data Handling and Graphical Treatment

Quantitative techniques generate datasets that can be plotted to examine rate trends. For continuous measurements such as mass or gas volume, rate is obtained from the gradient of the curve at any chosen point.

Rate (of reaction) = Change in measured variable ÷ Time

Change in measured variable = Mass loss, gas volume, or alternative observable; expressed with appropriate units

Time = Duration of measurement; seconds or minutes

Between data collection and interpretation, good practice includes:

Tabulating raw data systematically

Recording uncertainties of apparatus

Using appropriate graph scales

Identifying anomalous results and repeating if necessary

Considering whether initial or mean rates are more appropriate

These actions support accuracy and help meet OCR’s expectation of appropriate practical techniques and data handling.

Practical Techniques: Ensuring Accuracy

Controlling Variables

To maintain reliability and allow valid comparisons, the following must be controlled:

Temperature, which significantly influences kinetic energy and rate

Concentration of reactants

Volume of solutions

Surface area of solids, particularly in heterogeneous reactions

Catalyst presence or absence

Changing only one variable at a time ensures the effect on rate can be meaningfully interpreted.

Recording Data Effectively

Well-designed recording strategies improve precision:

Use electronic timers for consistent time measurement

Pre-weigh reactants to minimise delays

Start timing immediately upon mixing

Use repeat trials to improve reliability and identify systematic deviations

Consider the need for stirring to maintain homogeneity

Each technique should be matched to the reaction’s features and the level of precision required.

Safety and Good Laboratory Practice

Although not directly measured as part of the rate experiment, safety underpins all practical work:

Wear goggles when handling acids or reactive metals

Consider pressure build-up when collecting gases

Avoid using sealed containers for gas-evolving reactions

Dispose of reactants according to school and regulatory guidelines

Safe practice ensures repeatability and reliability while supporting the development of competent experimental technique.

FAQ

The key is to identify a physical property that changes clearly and measurably as the reaction proceeds.

Choose a method based on:

Whether a gas is produced

Whether a visible change occurs

How fast the reaction is expected to take place

Slow reactions suit continuous measurements (mass or volume), while rapid or visually distinctive reactions may suit time-based endpoints.

Temperature directly affects particle kinetic energy, so even small fluctuations can significantly change reaction rate.

For comparable data, all measurements must be taken at a constant temperature using:

A thermostated water bath

Pre-equilibrated reactants

Insulated apparatus where necessary

Failing to control temperature introduces systematic error, making trends unreliable.

Sampling should reflect how quickly the reaction rate changes.

In fast reactions, readings must be taken every few seconds to capture steep early gradients.

In slower reactions, less frequent sampling prevents unnecessary disturbance without losing detail.

The aim is to generate a smooth curve that shows both the initial rate and later slowing stages.

Random error arises mainly from subjective judgement.

It can be reduced by:

Using the same observer for all trials

Keeping the reaction vessel at a fixed height and angle

Ensuring consistent lighting

Averaging multiple repeat times

These steps improve reproducibility even though the endpoint remains qualitative.

Any leak causes underestimation of gas volume, reducing accuracy.

Loose tubing, poorly fitted bungs, or cracked syringes allow gas to escape unnoticed.

Before data collection, students should:

Test airtightness by gently applying pressure and checking for movement

Ensure tubing fits securely

Replace worn or stiff syringe plungers

Good sealing ensures that all generated gas is measured and rate values remain valid.

Practice Questions

A student investigates the rate of reaction between magnesium and hydrochloric acid by measuring the volume of hydrogen gas produced over time.

Explain why a gas syringe is more suitable than an inverted measuring cylinder for collecting the gas.

(1–3 marks)

Award up to 3 marks for the following points:

Gas syringes provide more accurate volume measurements (1 mark)

Gas syringes prevent loss of gas because the system can be made airtight (1 mark)

Inverted measuring cylinders may allow gas to dissolve in water or escape during setup, reducing accuracy (1 mark)

A reaction between sodium thiosulfate and hydrochloric acid forms a precipitate of sulfur, causing a cross beneath the reaction flask to disappear from view.

A student uses this setup to compare rates at different temperatures.

Discuss the strengths and limitations of this method for determining reaction rate, and describe how the student should collect and process the data to obtain comparable rate values.

(4–6 marks)

Award marks for any valid points below, up to 6 marks total.

Strengths (maximum 2 marks):

Method gives a clear visual endpoint (1 mark)

Useful for comparing relative rates under different conditions (1 mark)

Limitations (maximum 2 marks):

Human judgement introduces uncertainty when deciding when the cross ‘disappears’ (1 mark)

Turbidity increases gradually, so the endpoint is subjective and may vary between repeats (1 mark)

Lighting or viewing angle can affect when the cross is judged to vanish (1 mark)

Data collection and processing (maximum 3 marks):

Student should measure the time taken for the cross to become obscured at each temperature (1 mark)

Keep all other variables constant: concentrations, volumes, and positioning of flask and cross (1 mark)

Rate should be compared using 1 ÷ time for disappearance to give values proportional to rate (1 mark)

Multiple repeats at each temperature should be taken and averaged to improve reliability (1 mark)

Accept any valid, clearly explained alternatives.