OCR Specification focus:

‘Increasing concentration or gas pressure raises collision frequency and reaction rate; rate from gradients of suitable time-dependent measurements.’

Understanding how particles collide and how often collisions occur is central to predicting reaction rates. Changes in concentration or pressure alter collision frequency, directly influencing reaction behaviour.

Collision Theory: Fundamental Ideas

Collision theory provides a conceptual framework for explaining why chemical reactions occur and how reaction conditions influence their rates. A reaction proceeds only when particles collide in a way that leads to a successful transformation of reactants into products.

Requirements for a Successful Collision

Two conditions must be satisfied for a collision to result in reaction:

Sufficient energy to overcome the activation barrier.

Correct orientation of reacting particles so the necessary bonds can be formed or broken.

Activation energy: The minimum energy required for particles to react upon collision.

The activation energy threshold explains why most collisions in a sample do not lead to reaction, even when particles are constantly moving and interacting. As a result, reaction rate depends on both the frequency and quality of collisions.

Collision Frequency and Reaction Rate

Collision frequency refers to the number of collisions occurring per unit time. Only a fraction of these collisions result in successful reactions, yet increasing the total number of collisions proportionally increases the number of successful events, provided that energy and orientation criteria are met.

A reaction rate can be measured experimentally using gradients of time-dependent data, such as concentration–time or volume–time graphs, allowing the change in reactants or products to be monitored throughout the reaction.

Reaction rate: The change in concentration of a reactant or product per unit time.

Because rate depends on both collision frequency and successful collision probability, any factor altering particle density or spacing can significantly influence how quickly a reaction proceeds.

Effect of Concentration on Reaction Rate

Increasing concentration in a solution increases the number of particles per unit volume. With particles more closely packed, collisions occur more frequently.

How Concentration Influences Collisions

When concentration rises:

The average distance between reactant particles decreases.

The collision frequency increases because particles encounter each other more often.

The rate of reaction increases, assuming the proportion of collisions meeting activation energy remains constant.

These effects are especially clear in homogeneous aqueous reactions, where reactants dissolve uniformly and particle spacing is directly tied to concentration.

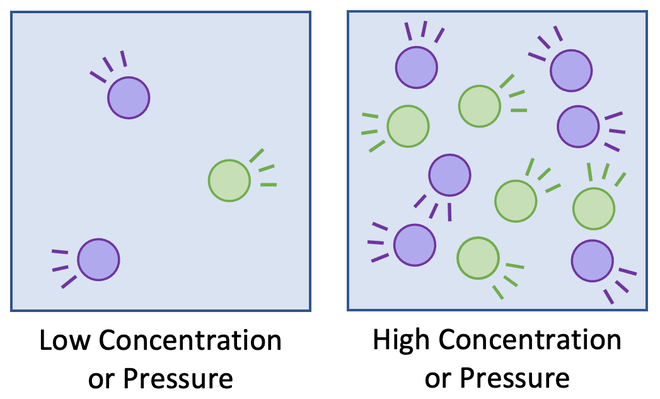

This diagram compares a system at low concentration/pressure with one at high concentration/pressure. More particles in the same volume increase collision frequency. This supports the collision‑theory explanation of why increasing concentration or gas pressure increases reaction rate. Source

Concentration: The amount of solute per unit volume of solution.

Between any two definition blocks, explanatory commentary should reinforce conceptual understanding. Increasing concentration does not alter activation energy; rather, it increases opportunities for successful collisions to occur.

Limitations of Concentration Changes

At very high concentrations, secondary factors may arise:

Increased solution viscosity can reduce particle mobility.

Heat changes during rapid reactions can influence measured rate values.

Side reactions or saturation effects may occur depending on the system.

Despite these considerations, the core idea remains central to OCR: more concentrated solutions yield higher collision frequencies and therefore higher reaction rates.

Effect of Pressure on Reaction Rate

For reactions involving gases, pressure plays a role equivalent to concentration in solutions. Gas particles move freely, spreading to fill their container; altering pressure changes how tightly packed the particles are.

Pressure and Particle Density

When pressure is increased at constant temperature:

Gas particles are forced into a smaller volume, increasing density.

Collision frequency rises because particles travel shorter distances between collisions.

Reaction rate increases, provided that temperature and activation energy conditions are unchanged.

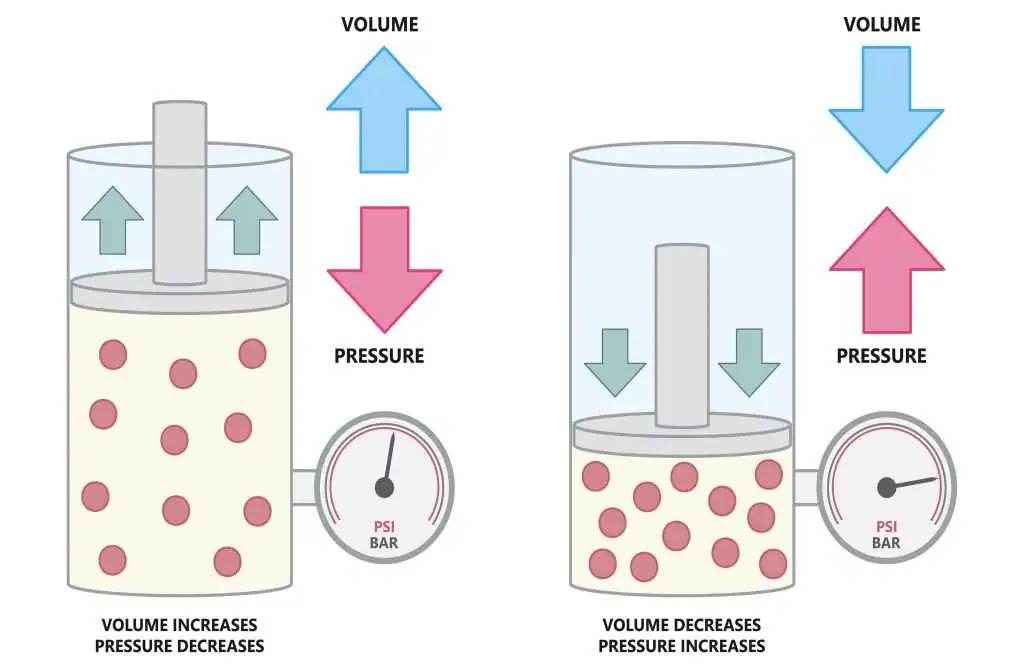

This figure compares a gas at high volume/low pressure with the same gas compressed to lower volume/higher pressure. Compression increases particle density and collision frequency. The labels illustrating the volume‑pressure relationship go slightly beyond the OCR requirement but remain consistent with collision theory. Source

Pressure: The force exerted per unit area by gas particles colliding with container walls.

A normal explanatory sentence reinforces that increased pressure affects only gas-phase reactions or heterogeneous reactions where a gaseous reactant is involved. Pressure has no effect on reactions occurring solely in the solid or liquid state.

Industrial and Practical Importance

Control of pressure is essential in large-scale gas-phase processes, such as ammonia synthesis or catalytic cracking, because adjusting pressure is an efficient way to modify collision frequency without changing temperature or catalyst conditions.

Measuring Reaction Rate: Gradient Methods

According to the OCR specification, reaction rate is determined from gradients of suitable time-dependent measurements. These may involve tracking changes that directly correlate with the progress of a reaction.

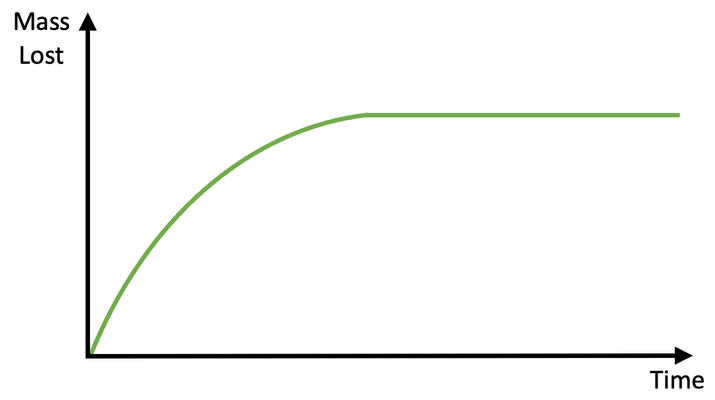

This time–volume graph shows how reaction rate is fastest initially and slows as reactants are used up. The gradient at any point represents reaction rate. Although this example uses gas volume, the same gradient method applies to all suitable time‑dependent measurements. Source

Common Time-Dependent Measurements

Mass change when a gaseous product escapes.

Gas volume collected over time.

Concentration changes monitored using titration, pH measurement or colorimetry.

Rate (change in concentration per unit time) = Δ[Reactant or Product] / Δt

Δ[Reactant or Product] = Change in concentration (mol dm⁻³)

Δt = Change in time (s)

A normal sentence is required before transitioning. The gradient of a concentration–time graph at any point represents the instantaneous rate, while gradients over longer intervals provide average rates.

Linking Collision Theory to Measured Rates

Time-dependent measurements reflect how quickly reactants are consumed or products formed. When concentration or pressure increases, steeper gradients appear because more successful collisions occur per unit time. Thus collision theory offers the conceptual basis that explains the empirical measurement of reaction rate.

Summary of Key Effects

Higher concentration → more particles per volume → increased collision frequency → higher reaction rate.

Higher pressure → more gas particles per volume → increased collision frequency → higher reaction rate.

Rate is determined experimentally using gradients of measured data, directly linking theory with observable behaviour in chemical systems.

FAQ

Particles must approach each other in a way that allows the correct bonds to break and form. Even when activation energy is met, most collisions fail because the reacting groups are not aligned.

Orientation requirements vary depending on molecular shape.

Linear molecules may require fewer specific orientations.

Complex or bulky molecules often have fewer effective collision angles, reducing reaction rate even at high concentrations or pressures.

Gas particles move freely and occupy the full container, so compressing them produces a large change in particle density.

In liquids, particles are already closely packed, meaning concentration changes alter spacing less dramatically.

Thus, gas-phase reactions typically show a more pronounced sensitivity to pressure adjustments.

At extremely high pressures:

Gas behaviour deviates from ideal-gas assumptions, altering predictions about collision frequency.

Increased intermolecular forces can reduce kinetic energy available for effective collisions.

Equipment limits and safety constraints prevent industrial processes from increasing pressure indefinitely.

Particles in a sample have a range of speeds due to thermal energy distribution. Faster particles collide more frequently and more effectively than slower ones.

At a constant concentration or pressure, raising temperature broadens and shifts this distribution, meaning a greater fraction of particles collide with sufficient energy.

Frequent collisions alone do not guarantee a fast reaction. Other limiting factors include:

Very high activation energy, meaning few collisions are successful.

Poor molecular orientation, especially in complex organic molecules.

The presence of strong bonds requiring significant input energy before any reaction can occur.

These factors reduce the proportion of successful collisions even in dense particle environments.

Practice Questions

Explain why increasing the concentration of a reactant in solution increases the rate of reaction, according to collision theory.

(2 marks)

1 mark – States that increasing concentration increases the number of particles per unit volume.

1 mark – States that this increases collision frequency or likelihood of successful collisions.

A reaction between two gases occurs in a sealed container. Using collision theory, explain how each of the following changes affects the rate of reaction:

a) Increasing the pressure of the gases.

b) Decreasing the temperature.

c) Adding a catalyst.

Your answer should refer to particle behaviour and successful collisions.

(5 marks)

a) Increasing pressure (up to 2 marks)

1 mark – Particles are forced into a smaller volume / increased particle density.

1 mark – Increased collision frequency leads to a higher rate of reaction.

b) Decreasing temperature (up to 2 marks)

1 mark – Particles have less kinetic energy.

1 mark – Fewer particles have energy equal to or greater than the activation energy, leading to fewer successful collisions.

c) Adding a catalyst (1 mark)

1 mark – Provides an alternative reaction pathway with lower activation energy, increasing the proportion of successful collisions.