OCR Specification focus:

‘Describe techniques and procedures to observe qualitative shifts in equilibrium position when concentration or temperature is altered.’

Understanding how equilibria respond to changes in concentration and temperature is essential for interpreting chemical behaviour. Practical methods allow students to observe qualitative equilibrium shifts directly in laboratory settings.

Investigating Equilibrium Changes

Practical investigation of dynamic equilibrium focuses on observing visible or measurable changes when a system experiences external disruption. These procedures provide qualitative evidence for shifts in equilibrium position rather than calculating numerical values. Students must be confident in recognising changes produced by variation in concentration and temperature, as required by the OCR specification.

Dynamic Equilibrium Essentials

A dynamic equilibrium exists when the rates of the forward and reverse reactions are equal and concentrations remain constant. Although this subsubtopic does not introduce new principles, all practical methods used rely on detecting changes when this balance is disturbed.

Identifying Qualitative Shifts

A qualitative shift refers to observable changes—such as colour, precipitate formation, or intensity differences—that indicate the equilibrium composition has changed. These shifts do not quantify amounts but confirm directionality of change. Observations frequently arise from equilibria involving transition-metal complexes or systems where reactants and products have distinct physical properties.

Techniques for Investigating Concentration Changes

Changing concentration is one of the most accessible methods for exploring equilibrium shifts experimentally. Such changes alter the relative amounts of reactants or products, creating a temporary imbalance until the equilibrium re-establishes.

General Laboratory Approach

Students should recognise the following core methods used to investigate concentration effects:

Addition of reactants or products to disturb the equilibrium by increasing one side of the balanced system.

Dilution using distilled water when aqueous equilibria are present, influencing ion concentration and equilibrium position.

Selective removal of species, for example using precipitating agents, which decreases concentration of targeted ions.

Use of complexing agents to bind specific ions and shift equilibrium composition.

After these adjustments, the system responds with observable changes. These may include:

Colour deepening or fading.

Formation or dissolution of a precipitate.

Gas evolution or disappearance in equilibria involving gaseous species.

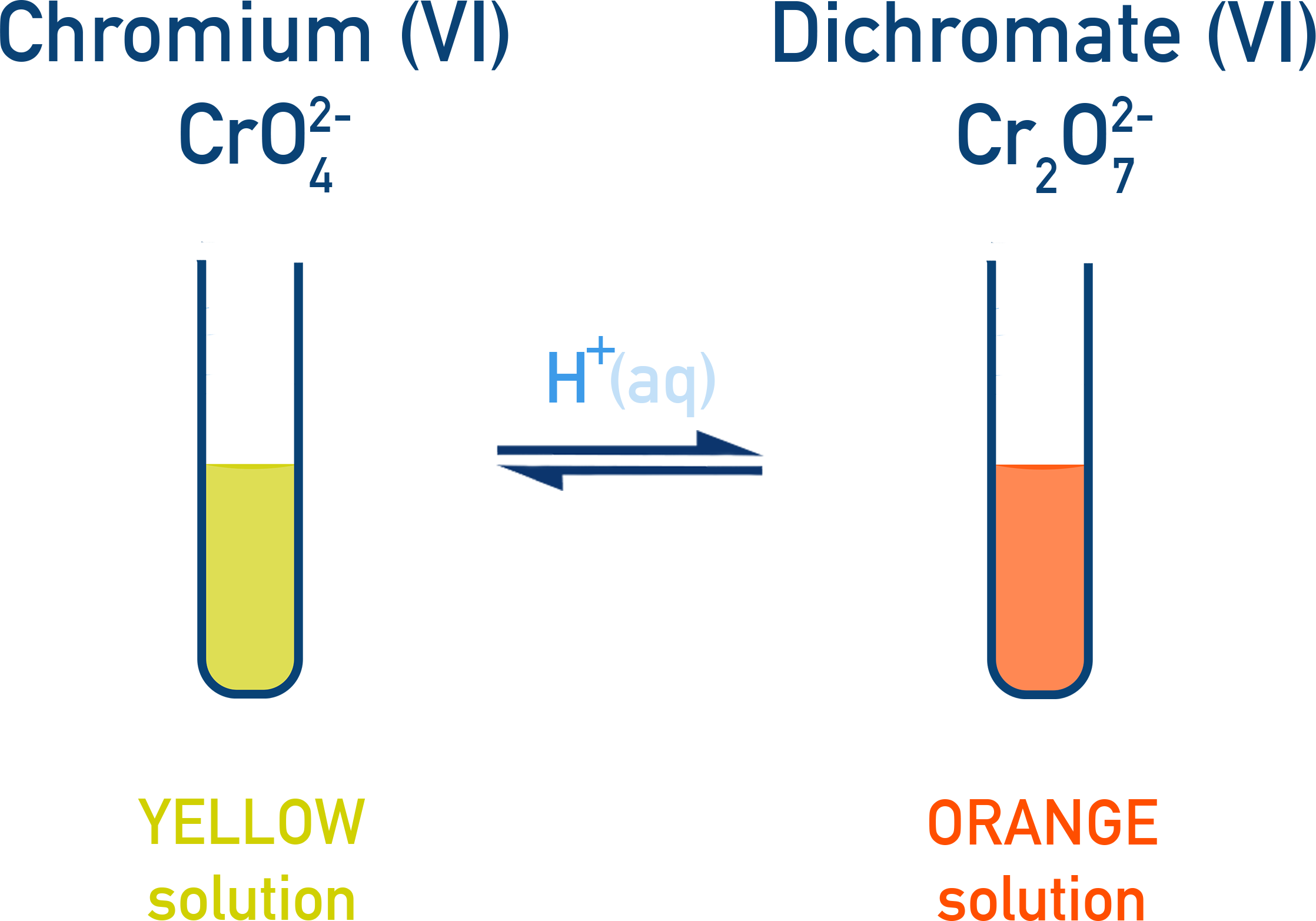

A classic concentration experiment uses the equilibrium between yellow chromate(VI) ions and orange dichromate(VI) ions, where adding acid or alkali produces an obvious colour change.

Chromate–dichromate equilibrium: yellow CrO4^2− converts to orange Cr2O7^2− when H+(aq) is added, illustrating a concentration-induced shift in equilibrium. The ion labels add minor extra detail but remain directly relevant to the equilibrium concept. Source

Key Experimental Considerations

Solutions should be mixed thoroughly to ensure uniform reaction conditions.

Observations must be recorded immediately because some equilibria re-establish rapidly.

Temperature must remain constant during concentration investigations unless intentionally varied.

Normal laboratory glassware such as test tubes, dropping pipettes, and volumetric equipment are sufficient for these procedures. Ensuring accurate reagent volumes improves clarity of qualitative outcomes.

Techniques for Investigating Temperature Changes

Temperature variation alters the equilibrium position by affecting relative favourability of endothermic and exothermic directions. Unlike concentration manipulation, which affects reaction quotients directly, temperature changes influence equilibrium constants and produce distinctive qualitative effects.

Determining Direction of Equilibrium Shift

When temperature is altered, students must interpret changes using observable features rather than calculations. The equilibrium shifts:

Towards the endothermic direction when temperature is increased.

Towards the exothermic direction when temperature is decreased.

These shifts are identified by:

Changes in colour intensity for equilibria involving coloured species.

Formation or dissolution of precipitates in temperature-dependent equilibria.

Changes in gas pressure or volume when gaseous equilibria are involved.

Temperature changes can be explored using the equilibrium between pink hexaaquacobalt(II) and its more blue or purple chloro complex, where heating drives the colour towards the product side.

Cobalt(II) equilibrium before and after heating: the pink solution becomes purple-blue upon warming, demonstrating a temperature-driven shift in equilibrium position. Labels indicate the heating step without adding concepts beyond those in the notes. Source

Practical Temperature Control

Common laboratory methods include:

Gentle warming using a water bath or warm water addition to avoid rapid or uneven heating.

Cooling using ice baths or cold-water immersion to reduce temperature steadily.

Avoiding direct flame heating, which creates localised hot spots and risks decomposition.

Temperature must be altered gradually, and mixtures should be allowed time to reach new thermal equilibrium before observations are made. Students should recognise that some systems show gradual, subtle colour transitions, requiring careful attention.

Recording Qualitative Observations

Accurate qualitative data are essential for interpreting equilibrium behaviour. Students should record:

Initial appearance of the equilibrium mixture.

Reagents added and temperature adjustments made.

Immediate changes upon disturbance.

Changes after the system has settled into a new equilibrium.

Observational language should be precise. Terms such as ‘darker blue’, ‘paler pink’, ‘precipitate formed’, ‘gas bubbles observed’, or ‘solution cleared’ help to describe shifts clearly.

Safety and Good Laboratory Practice

Although equilibrium investigations are usually low-hazard, correct handling enhances reliability and safety:

Wear appropriate eye protection and gloves where required.

When heating, ensure glassware is heatproof and avoid sudden temperature changes that may cause breakage.

Dispose of metal-ion solutions following school or institutional protocols.

Equilibrium Position: The relative amounts of reactants and products present at equilibrium, indicating whether the system lies to the left (reactants) or right (products).

Clear interpretation of equilibrium position is essential because qualitative investigations rely on recognising which side of the reaction becomes favoured after a disturbance.

Layered Example Observations (Non-numerical)

These patterns commonly arise in laboratory investigations and support conceptual understanding:

Increasing concentration of a coloured reactant often intensifies that colour until the opposing reaction reduces its effect.

Adding a product may suppress its characteristic properties, showing the reverse direction is favoured.

Heating a mixture may cause colour shifts associated with the endothermic pathway, while cooling produces the opposite trend.

Precipitates may dissolve when equilibrium shifts towards ions and re-form when it shifts back.

Analytical Reflection During Practical Work

Throughout these investigations, students should continually link observable shifts to underlying equilibrium principles. Noting how each manipulation affects reactant or product proportions reinforces conceptual mastery and prepares students for more advanced equilibrium analysis.

FAQ

Dilution decreases the concentration of all aqueous species, but a true equilibrium shift changes the relative proportions of reactants and products.

A reliable approach is to compare observations before and after allowing the system to settle. If the colour or appearance continues to move in a clear direction after mixing, the equilibrium has shifted rather than simply becoming lighter through dilution.

Transition-metal ions often form complexes with distinct colours, making shifts easy to see. Their equilibria also respond quickly to changes, allowing observations in real time.

Commonly studied systems include cobalt(II), chromium(VI), and iron(III) ions because they provide clear qualitative evidence of concentration or temperature changes without needing quantitative analysis.

Some equilibria involve colourless ions or species with very similar appearances, limiting observable differences.

Additional limiting factors include:

very small equilibrium constants

sluggish kinetics that delay observable changes

interference from side reactions or impurities

insufficient reagent concentration to produce noticeable contrast

Using consistent lighting and viewing through a white background reduces subjective interpretation of colour changes.

Students can also:

compare samples side-by-side

record changes immediately to avoid missing transient shifts

use descriptive terms such as “darker”, “paler”, “more orange”, or “less blue” rather than ambiguous wording

Temperature affects the equilibrium constant, but the resulting shift may be subtle if the enthalpy change is small. Visible differences can therefore be limited.

Some systems require time to reach thermal equilibrium, so colour changes may develop gradually. In addition, excessive heating can cause decomposition, preventing the expected shift from being observed.

Practice Questions

A pale yellow equilibrium mixture containing chromate(VI) ions is treated with a small volume of dilute hydrochloric acid.

State the observable change and explain why this change occurs in terms of equilibrium position.

(2 marks)

Yellow solution turns orange. (1)

Addition of acid increases concentration of H+ ions, shifting equilibrium towards dichromate(VI) ions. (1)

A cobalt(II) chloride solution appears pink at room temperature but becomes blue when warmed.

A student investigates this temperature-dependent equilibrium by heating and cooling separate samples of the mixture.

(a) State what the colour change on heating indicates about the relative enthalpy of the forward reaction.

(b) Suggest two procedural considerations the student should follow when changing the temperature of the equilibrium mixture.

(c) Explain why qualitative observations rather than quantitative measurements are sufficient for this equilibrium investigation.

(5 marks)

(a)

The reaction producing the blue species is endothermic because heating favours the forward direction. (1)

(b) Any two of the following:

Temperature should be changed gradually to avoid overshooting or decomposition. (1)

Use a water bath or controlled heating method rather than direct flame. (1)

Allow the mixture to reach thermal equilibrium before recording observations. (1)

(c)

The investigation relies on observable colour changes to identify the direction of equilibrium shift, so numerical data are not required. (1)

Only the qualitative position of equilibrium is needed, not values for equilibrium constants or concentrations. (1)