OCR Specification focus:

‘Italy and the impact of the Vienna Settlement; unrest and nationalism’

The Vienna Settlement reshaped Italy after Napoleon’s fall. Its conservative framework suppressed reform, but unrest, secret societies, and nationalism continued to challenge the status quo.

The Vienna Settlement and Italy

Territorial Arrangements

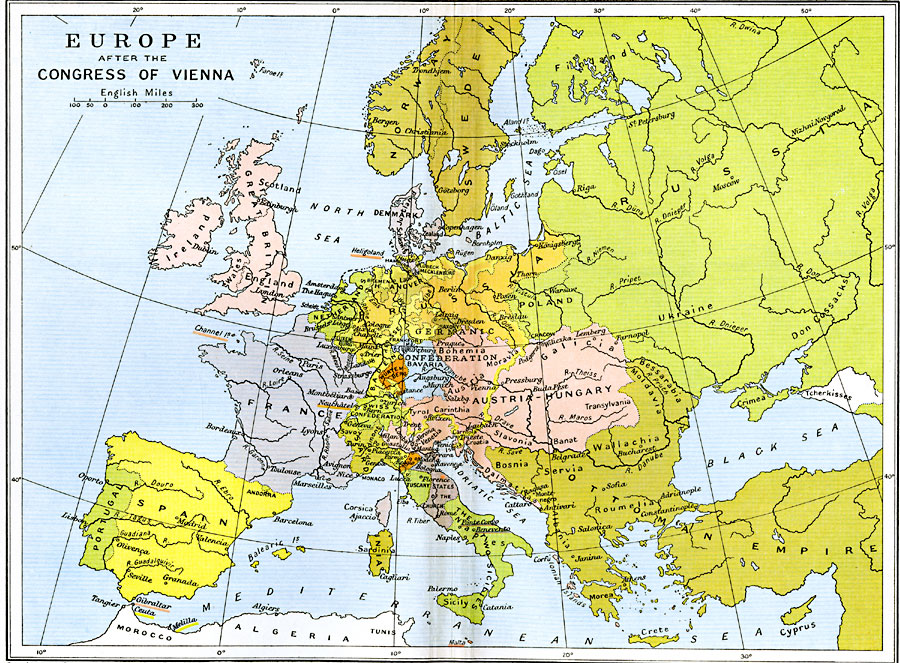

The Congress of Vienna (1814–1815) redrew the map of Europe after the Napoleonic Wars. For Italy, this meant the restoration of pre-revolutionary rulers and suppression of nationalist hopes.

Austria’s dominance: Austria gained direct control over Lombardy-Venetia, providing it with strong influence in northern Italy.

Restored monarchs: Former dynasties, such as the Bourbons in Naples and Sicily, were reinstated.

Papal States: The Pope regained control of central Italy.

Fragmentation: Italy was divided into multiple states, undermining the possibility of national unity.

Vienna Settlement: The diplomatic agreements of 1815 that restored monarchies, reinforced conservative rule, and established a balance of power to prevent revolution in Europe.

The Vienna Settlement deliberately opposed the principle of national self-determination, maintaining Italy as a patchwork of states under conservative rulers.

A labelled map of Italy after the Congress of Vienna (1815). Austrian-annexed territories in the north are highlighted, with restored states including the Papal States and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. Use it to trace fragmentation that hindered early nationalism. Source

Austrian Control and Conservatism

Austria sought to protect its security and political dominance:

Lombardy-Venetia became part of the Austrian Empire.

Austria exercised indirect influence over Tuscany, Parma, and Modena, where rulers were Habsburg relatives.

Austrian garrisons ensured the survival of reactionary regimes, providing military backing to suppress unrest.

Europe in 1815 showing the settlement reached at Vienna, including the Austrian Empire and the Italian states (Lombardy–Venetia, Papal States, Two Sicilies, Tuscany, Parma, Modena). Use this to situate Italian changes within the Concert of Europe. Source

The Rise of Unrest

Discontent with the Settlement

Many Italians resented Austrian control and foreign rule. Conservative policies, censorship, and the repression of liberal ideas caused frustration, particularly among the educated middle class.

Economic grievances: Heavy taxation and limited reforms worsened hardship.

Political repression: Liberal constitutions introduced under Napoleon were abolished.

Cultural resentment: The division of Italy undermined patriotic pride.

Secret Societies

With open political opposition impossible, Italians turned to clandestine groups.

The most significant was the Carbonari, a secret society promoting liberal and national ideals.

Their membership included students, professionals, and officers, especially in southern Italy.

Flag of the Carbonari (blue–red–black tricolour), associated with the clandestine movement active in the 1820s–1830s. It helps students link symbolic identity to the spread of liberal and national ideas. As a symbol, it adds no geographic detail and should be paired with textual explanation. Source

Carbonari: A network of secret revolutionary groups in Italy in the early 19th century, advocating constitutional government, freedom from foreign rule, and national independence.

Though often fragmented and loosely organised, secret societies spread discontent and laid early groundwork for nationalist resistance.

The Growth of Nationalism

Nationalist Sentiment

While nationalism remained weak compared to later decades, its seeds were sown after 1815:

Educated elites resented foreign control and the lack of Italian independence.

The memory of Napoleonic reforms, including legal equality and administrative efficiency, lingered as a contrast to restored monarchies.

Writers, poets, and intellectuals began to express the idea of an Italian identity, even if practical political unity seemed far away.

The Early Nationalist Vision

Nationalism in this period was diverse and inconsistent:

Some wanted constitutional monarchies within a looser Italian federation.

Others dreamed of republicanism and full independence from Austria.

Support was limited geographically and socially; peasants were largely indifferent, while middle-class liberals and some aristocrats drove the movement.

Forms of Resistance

Popular Unrest

Local uprisings occurred sporadically, often triggered by:

Economic hardship and food shortages.

Anger at taxation or unpopular rulers.

Inspiration from broader European liberal movements.

Influence of Secret Societies

The Carbonari and other groups channelled discontent into action:

Their networks helped organise conspiracies against rulers in Naples and Piedmont.

Despite repression, their ideas influenced future generations of revolutionaries, including Giuseppe Mazzini.

Austrian Response

Austria’s determination to maintain the conservative order meant swift intervention:

Revolts were crushed with military force.

Political police and censorship suppressed dissent.

Any hint of nationalist agitation was closely monitored.

The Balance Between Control and Resistance

Conservative Strengths

Austrian military power provided security for restored monarchies.

The Catholic Church supported conservative rulers, helping to legitimise their authority.

Limited support for nationalism meant uprisings rarely mobilised mass participation.

Weaknesses of the Settlement

The reliance on repression deepened resentment.

Italy’s division left it vulnerable to future revolutionary movements.

The inability to accommodate reform or liberal aspirations created instability.

The Significance of the Period 1815–1847

The years following the Vienna Settlement saw Italy trapped between conservative restoration and emerging nationalism. While Austrian dominance ensured temporary stability, it also fuelled resentment. Secret societies, unrest, and intellectual critiques of foreign rule signalled that the status quo would face continuing challenges. Although nationalism was not yet widespread or unified, this era laid the foundations for the more organised movements and revolutions that followed.

FAQ

Austria saw northern Italy as a buffer zone that protected its southern borders from French aggression. Control of Lombardy-Venetia gave access to key trade routes and fortified positions, strengthening Austria’s strategic position.

The Habsburgs also wanted to prevent the spread of revolutionary ideas from France into central Europe. Dominating Italy allowed them to contain liberal and nationalist movements that might undermine their empire.

The Settlement restored fragmented states with differing laws, currencies, and tariffs. This discouraged trade and slowed industrial development.

Austrian-controlled Lombardy-Venetia had potential for growth but was heavily taxed to benefit Vienna.

The south remained largely agricultural and underdeveloped, with little encouragement for reform.

Overall, the Settlement reinforced divisions and stagnation, limiting Italy’s economic modernisation.

The Papal States were restored under direct papal rule, giving the Church significant temporal power. The papacy reinforced conservative values and opposed liberal reform.

Church control over education and censorship of publications limited the spread of nationalist or liberal ideas. Many Italians, particularly in central Italy, resented the lack of modernisation caused by papal authority.

The Carbonari operated through small secret cells, which made them harder for authorities to infiltrate. Members swore loyalty oaths and used symbols, such as flags and rituals, to build solidarity.

They spread liberal and nationalist ideals through coded messages, pamphlets, and clandestine meetings. While they lacked unified leadership, their methods helped ideas circulate widely, especially in Naples and Piedmont.

Most peasants were more concerned with daily survival, harvests, and taxation than abstract political ideals. Nationalism appealed mainly to middle-class professionals, soldiers, and students.

Peasants often saw revolutionary activity as disruptive, especially if it brought repression or heavier burdens. Limited literacy also meant they were less exposed to nationalist writings or secret society propaganda.

For peasants, loyalty remained local—to village, landlord, or church—rather than to an Italian national identity.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Name two Italian states directly influenced or controlled by Austria following the Vienna Settlement (1815).

Mark Scheme

1 mark for each correct state named, up to a maximum of 2 marks.

Acceptable answers include:

Lombardy-Venetia (directly annexed by Austria)

Parma (Habsburg ruler installed)

Modena (Habsburg ruler installed)

Tuscany (Habsburg ruler installed)

Question 2 (6 marks)

Explain two reasons why many Italians were dissatisfied with the outcomes of the Vienna Settlement (1815).

Mark Scheme

Award up to 3 marks for each well-explained reason, maximum 6 marks.

Credit the following points:

Foreign domination (up to 3 marks)

Austria directly controlled Lombardy-Venetia and exerted influence over Parma, Modena, and Tuscany (1 mark).

This undermined Italian independence and fostered resentment against foreign rule (1 mark).

Students may develop with reference to Austrian garrisons or suppression of uprisings (1 mark).

Suppression of liberal and nationalist reforms (up to 3 marks)

Liberal constitutions and reforms introduced under Napoleon were abolished (1 mark).

Restoration of conservative monarchies and censorship limited freedoms (1 mark).

This frustrated the educated middle class and those who valued Napoleonic reforms (1 mark).

Other valid reasons may include: economic hardship due to taxation, cultural resentment over Italy’s fragmentation, or lack of national unity.

Marks should be awarded for clarity and development, not just identification.