AP Syllabus focus:

‘Describe how lipids are typically nonpolar, hydrophobic molecules whose structure and function depend on how their subcomponents are assembled.’Lipids are a diverse group of biological molecules linked by shared chemistry: lots of nonpolar carbon–hydrogen bonds. Their relative insolubility in water and their roles in cells depend strongly on how lipid subunits are connected.

What Makes Lipids “Lipids”

Lipids are grouped by properties more than by a single common polymer structure. Most lipids contain extensive hydrocarbon regions (chains or rings), which largely determine their interactions with water.

Lipid: A biological molecule that is largely nonpolar and water-insoluble, often composed of hydrocarbon chains and/or rings; lipid structure and function vary with how subcomponents are assembled.

Many lipids have few polar functional groups compared with carbohydrates or proteins, so they cannot form enough hydrogen bonds with water to dissolve well.

Nonpolarity and Hydrophobicity

Water is polar, so it interacts best with polar or charged substances. In contrast, most lipid regions are dominated by C–H and C–C bonds, which are nonpolar because electrons are shared relatively evenly. As a result, water does not strongly attract lipid surfaces.

Hydrophobic: Describes substances that do not mix well with water; hydrophobic molecules are typically nonpolar and tend to cluster together in aqueous environments.

Hydrophobic substances are not “repelled” by water in a literal force-like way; instead, water molecules preferentially hydrogen-bond with each other, limiting contact with nonpolar surfaces. This drives lipid molecules to aggregate, reducing the nonpolar surface area exposed to water.

Key Chemical Patterns to Recognise

Long hydrocarbon chains (many C–H bonds) → strongly hydrophobic

Few electronegative atoms (like O or N) → limited polarity

Small polar regions (like –OH or phosphate-containing groups) can increase interaction with water, but often do not outweigh large nonpolar regions

How Assembly of Subcomponents Changes Lipid Function

The syllabus emphasis is that lipid structure and function depend on how their subcomponents are assembled. Common subcomponents include fatty acids (hydrocarbon tails with a polar carboxyl end), glycerol, phosphate-containing groups, and hydrocarbon ring structures.

Triacylglycerols (Fats and Oils) as an Assembly Outcome

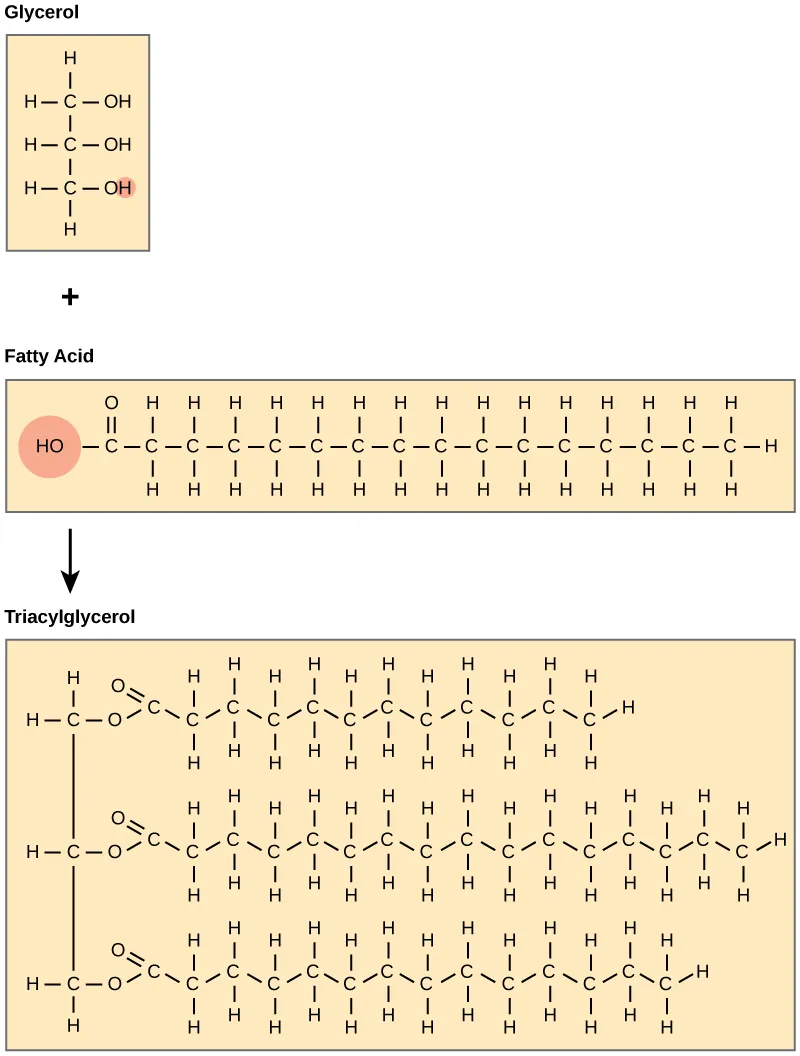

When glycerol is linked to three fatty acids, the result is a molecule with a small polar region and three large nonpolar tails.

Triacylglycerol formation is shown by attaching three fatty acids to a glycerol backbone via dehydration (ester bond) reactions. The figure highlights how a relatively small polar glycerol/carboxyl region contrasts with three long hydrocarbon chains, explaining why the assembled molecule is strongly hydrophobic overall. Source

This assembly creates a molecule that is:

Highly hydrophobic overall

Poorly soluble in cytosol

Prone to forming large lipid droplets rather than dispersing in water

Because the nonpolar region dominates, triacylglycerols minimize contact with water by clustering, which is a direct consequence of their assembled subunits.

Amphipathic Lipids: Mixed Polarity from Mixed Subunits

Some lipids contain both substantial nonpolar regions and a clearly polar “end” due to the way subcomponents are combined.

Amphipathic: Having both hydrophobic (nonpolar) and hydrophilic (polar or charged) regions within the same molecule.

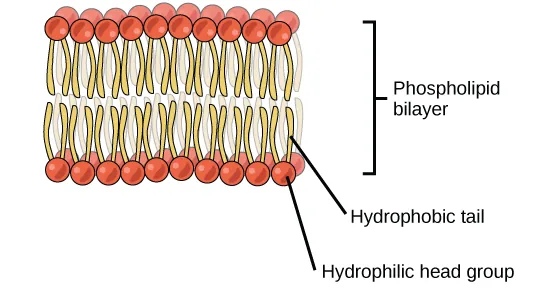

An amphipathic lipid’s behavior in water follows from its assembly:

The hydrophobic portion avoids water

The hydrophilic portion interacts with water

The molecule tends to arrange so that polar parts face water while nonpolar parts are shielded

A phospholipid bilayer is illustrated with hydrophilic (polar) head groups oriented toward the aqueous environments and hydrophobic fatty-acid tails packed in the interior. This arrangement demonstrates how amphipathic lipid structure drives spontaneous self-assembly into membranes in water. Source

This property emerges specifically from joining a polar subcomponent (head group) to nonpolar hydrocarbon regions (tails).

Ring-Based Lipids

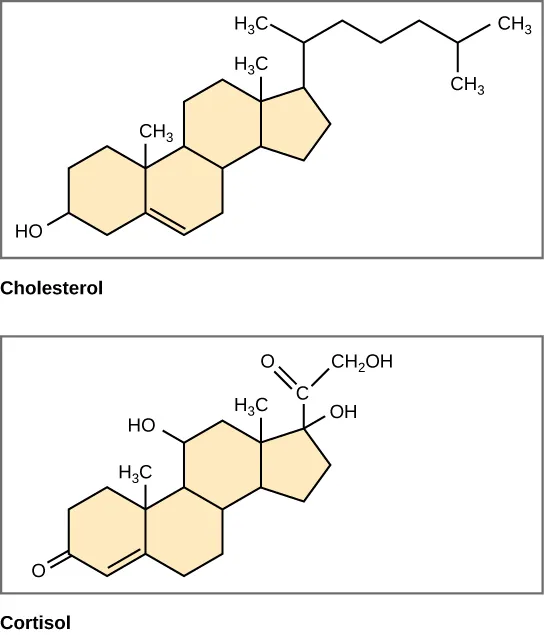

Some lipids are built primarily from fused hydrocarbon rings rather than long chains.

Steroid structures (e.g., cholesterol and cortisol) are shown as four fused hydrocarbon rings with a small number of polar functional groups (such as an –OH). The diagram emphasizes that large ring-based hydrocarbon regions remain mostly nonpolar, so these lipids are generally hydrophobic unless modified by additional polar groups. Source

Even without long tails, extensive ring hydrocarbons still create large nonpolar surfaces, so these molecules remain mostly hydrophobic unless they contain specific polar functional groups.

Biological Implications of Hydrophobicity (Without Leaving the Topic)

Hydrophobicity influences where lipids are found and how cells handle them:

Compartmentalisation: hydrophobic molecules tend to separate from water-based cytosol into distinct droplets or phases

Interactions with proteins: proteins may bind lipids via hydrophobic pockets, helping position or transport lipids in aqueous environments

Functional versatility: by changing which subcomponents are attached (and how many polar groups are included), cells produce lipids suited for different tasks while keeping the core hydrophobic chemistry

What to do With Unfamiliar Lipid Structures

When shown a lipid diagram, predict properties from subunits:

More hydrocarbon and fewer polar groups → more nonpolar and hydrophobic

A clear polar/charged “head” plus hydrocarbon “tail(s)” → likely amphipathic

Function often follows from this chemistry: where it can exist in a cell and how it associates with water

FAQ

Few biological lipids are perfectly nonpolar; many contain at least one polar functional group (for example, a hydroxyl). Whether they behave as “hydrophobic” depends on the balance between polar groups and hydrocarbon surface area.

Detergents are amphipathic, so they can surround lipid/grease with their hydrophobic parts while presenting hydrophilic parts to water. This forms small suspended particles that can be rinsed away.

Clustering reduces the nonpolar surface area exposed to water. Water can then maintain more hydrogen bonding with itself, which is energetically favourable compared with organising around many separate nonpolar surfaces.

Lipids typically show long stretches of C–C/C–H bonds and relatively few oxygens. Carbohydrates usually have many oxygen-containing groups (like multiple –OH) distributed throughout the molecule.

Cells often sequester lipids into droplets or associate them with proteins that provide hydrophobic binding sites. This shields nonpolar regions from water while allowing controlled movement and localisation.

Practice Questions

Explain why most lipids are insoluble in water. (2 marks)

States lipids are largely nonpolar / have many C–H bonds (1)

Links nonpolarity to inability to form sufficient hydrogen bonds with water, so they do not dissolve (1)

A student compares a triacylglycerol with an amphipathic lipid. Describe how differences in subunit assembly affect their overall polarity and behaviour in water. (5 marks)

Triacylglycerol described as glycerol + three fatty acids (1)

Explains triacylglycerol is mostly nonpolar/hydrophobic due to extensive hydrocarbon regions (1)

States amphipathic lipid has both a polar region and nonpolar hydrocarbon region because of its assembled subunits (1)

Predicts amphipathic lipids orient with polar part towards water and nonpolar part away from water (1)

Predicts triacylglycerols aggregate into droplets/clumps in water rather than dispersing (1)