AP Syllabus focus:

‘Define the derivative of a function f as another function f′(x), where f′(x) = lim₍h→0₎ [f(x + h) − f(x)] / h whenever this limit exists for that x.’

The derivative function formalizes how a quantity changes at every input value, using limits to capture instantaneous change and produce a new function describing local behavior.

Defining the Derivative Function

The derivative function describes how a function’s output changes with respect to its input at each point where the limit-based definition exists.

Derivative Function: The function defined by the limit whenever this limit exists.

The derivative function is foundational in calculus because it allows us to analyze variation across an entire domain rather than at a single point. When the limit exists for each relevant , the result is a new function that encodes instantaneous rates of change.

Understanding the Limit Structure

The expression inside the derivative’s definition is called a difference quotient, and it measures how much the function changes over an interval of length .

Difference Quotient: An expression of the form measuring the average rate of change over a small interval.

By shrinking the interval length toward zero, the difference quotient converges—when the limit exists—to a precise instantaneous rate.

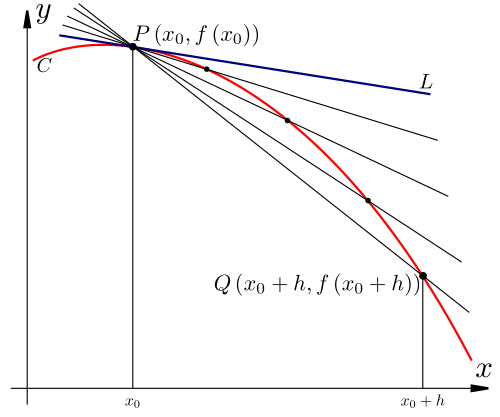

A curve C is shown with a secant line joining the points at x and x+h. As h becomes smaller, the secant line rotates toward the tangent line L, illustrating the limit process that defines the derivative. This visual emphasizes that is obtained as the limiting slope of secant lines as the two points on the graph merge into one. Source.

This limit-based viewpoint is essential because many real-world and mathematical processes rely on changes occurring over infinitesimally small intervals.

Equation Form of the Derivative Function

Students benefit from seeing the derivative written in standard symbolic form, which reinforces its structure and purpose.

= instantaneous rate of change of with respect to

= original function value at

= increment approaching zero

This expression highlights the relationship between the original function and its derivative: the derivative evaluates how changes, while itself provides the base values from which those changes are measured.

Interpreting as a New Function

Once defined, the derivative is treated as a standard function that can be graphed, tabulated, or analyzed algebraically. Key interpretation points include:

Domain considerations: is defined only where the limit exists.

Continuity implications: Differentiability requires continuity, though continuity alone does not guarantee differentiability.

Behavioral insights: The sign and magnitude of reveal whether is increasing or decreasing and how rapidly.

A derivative function often provides a more revealing view of behavior than the original function, especially when analyzing trends, turning points, and local linear approximations.

The Derivative as a Function of Local Behavior

The derivative represents the instantaneous rate of change, a concept that generalizes to multiple contexts such as velocity, growth rate, and sensitivity analysis. Even in abstract settings, the derivative quantifies how outputs respond to infinitesimal input changes.

Instantaneous Rate of Change: The limit of average rates of change as the interval shrinks to zero, equal to the derivative when the limit exists.

This understanding reinforces why limits are essential: instantaneous behavior cannot be captured without letting interval lengths approach zero.

Connecting the Derivative to Graphs

Graphically, the derivative function describes the slope of the tangent line to the graph of at each point where the derivative exists.

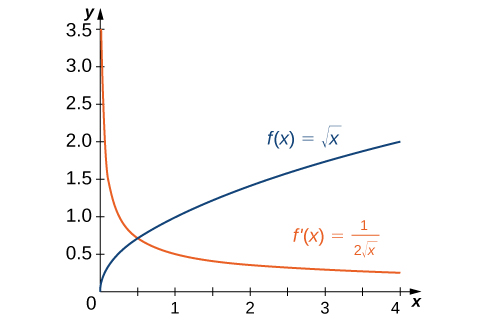

The graph of is plotted together with its derivative . For each x in the domain, the value of gives the slope of the tangent line to the graph of f at that point. The steep tangent near x=0 corresponds to very large values of there, indicating a vertical tangent in the original graph. Source.

A tangent line provides the best linear approximation to the function near that point.

Students should note the following conceptual connections:

The derivative reflects the steepness and direction of the function’s graph.

Sharp corners or cusps may prevent the derivative from existing because the slope changes abruptly.

Smoothness in the graph typically corresponds to a well-defined derivative.

These connections help students appreciate the derivative as both an algebraic and geometric idea.

Viewing the Derivative as a Limit-Generated Rule

Although later techniques allow differentiation without computing limits every time, it is crucial to recognize that all derivative rules stem from the limit definition. The limit form ensures consistency across functions and validates shortcuts like the power rule.

Important ideas include:

Every derivative rule must agree with .

Limit-based reasoning ensures derivative formulas remain accurate for complex expressions.

Understanding the definition supports troubleshooting when functions behave unexpectedly.

This grounding in limits strengthens conceptual mastery and prepares students for more advanced derivative applications.

Structural Overview of Across a Domain

The derivative function often reveals patterns that are less apparent in itself.

Key observations:

If , the function is locally increasing.

If , the function is locally decreasing.

If , the function may have a local extremum or a point of inflection, depending on broader behavior.

These interpretations rely on the derivative being defined through limits, which guarantee precision in describing local variation.

The Central Role of Limits in Defining Derivatives

Limits ensure that the derivative function is not based on approximations but on exact instantaneous behavior. Without limits, one could only compute average changes, not instantaneous ones. By defining through the limit of a difference quotient, calculus establishes a rigorous, universally applicable framework for analyzing change.

FAQ

The slope between two points gives an average rate of change over an interval, not the behaviour at a specific point.

The limit definition forces the interval to shrink until the two points effectively coincide, capturing the function’s behaviour at an instant rather than across a stretch.

This ensures precision even when the graph is curved, where average slopes vary significantly with interval length.

For the derivative at a point to exist, the left-hand and right-hand difference quotients must approach the same value.

If they do not, the slope of the tangent line would depend on the direction of approach, which means no single tangent slope can be assigned.

This criterion distinguishes sharp changes, corners, or non-smooth points from smooth, differentiable behaviour.

Yes. When the tangent line is vertical, the difference quotient grows without bound as the interval shrinks.

If the limit tends to infinity, the derivative does not exist as a finite number.

This signals vertical tangency even when the function is continuous and smooth in appearance.

Direct substitution often gives indeterminate forms. Carefully rewriting expressions can reveal cancellations that allow the limit to be evaluated.

Typical strategies include:

• Rationalising expressions

• Factoring out common terms

• Rewriting piecewise definitions around the point of interest

These steps do not alter the function but make its local behaviour easier to analyse.

If a function is differentiable at a point, then at sufficiently small scales the graph appears almost straight.

The derivative value is the slope of this local linear approximation.

The limit definition formalises this by ensuring that the ratio of output change to input change stabilises as the interval shrinks, confirming that the function behaves linearly at that tiny scale.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A function f is defined for all real x. The derivative of f at x = 2 is defined using the limit of the difference quotient.

(a) Write the expression that defines f'(2) using the limit definition of the derivative.

(b) Briefly explain what this limit represents in terms of the graph of f.

Question 1

(a) 1 mark

• Correct limit expression: f'(2) = lim as h approaches 0 of [f(2 + h) − f(2)] / h.

(Any correct equivalent limit definition earns the mark.)

(b) 1–2 marks

• 1 mark: States that the limit represents the slope of the tangent line to the graph at x = 2.

• 1 mark: States that it represents the instantaneous rate of change of the function at x = 2.

(Maximum 2 marks for part (b).)

Total: 2–3 marks.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Let g be a differentiable function. The table below gives selected values of g(x).

x: 1, 1.1, 1.2

g(x): 3.2, 3.41, 3.65

(a) Using the limit definition of the derivative, estimate g'(1) by forming a suitable difference quotient.

(b) Explain why the estimate you obtained corresponds to the instantaneous rate of change of g at x = 1.

(c) State one reason why the true value of g'(1) might differ slightly from your estimate.

Question 2

(a) 2 marks

• 1 mark: Forms a correct difference quotient, for example (g(1.1) − g(1)) / 0.1 or (g(1.2) − g(1)) / 0.2.

• 1 mark: Computes an appropriate numerical estimate.

For instance: (3.41 − 3.2) / 0.1 = 2.1, or (3.65 − 3.2) / 0.2 = 2.25.

(Any reasonable estimate earns full credit.)

(b) 1–2 marks

• 1 mark: States that as the interval length becomes very small, the average rate of change approaches the instantaneous rate.

• 1 mark: Connects this idea to the definition of the derivative as a limit of difference quotients.

(c) 1–2 marks

• 1 mark: Identifies a valid reason (e.g., interval not small enough, rounding errors, table values only approximate).

• 1 mark: Provides a brief explanation of why this affects accuracy.

Total: 4–6 marks.