AP Syllabus focus:

‘Interpret second and higher derivatives as describing how earlier derivatives change, connecting them to concavity, motion, and other real-world applications.’

Higher-order derivatives reveal how earlier derivatives behave and change, providing insights into shape, motion, and real-world variability essential for deeper interpretation in calculus.

Interpreting Higher-Order Derivatives

Higher-order derivatives extend the idea of change beyond the first derivative, allowing us to analyze how rates themselves vary over time or with respect to another variable. Understanding these interpretations is central to modeling and explaining physical, geometric, and applied phenomena.

The Role of the First and Second Derivatives

The first derivative represents the instantaneous rate of change of a function. In many contexts, it measures velocity, growth rate, or slope. The second derivative captures how the first derivative changes, providing information about curvature, acceleration, and the function’s overall shape.

Second Derivative: The derivative of the first derivative, describing how the rate of change itself varies.

Because the second derivative influences the behavior of the graph of a function, it is closely tied to concavity, a concept describing how the curve bends and how slopes evolve.

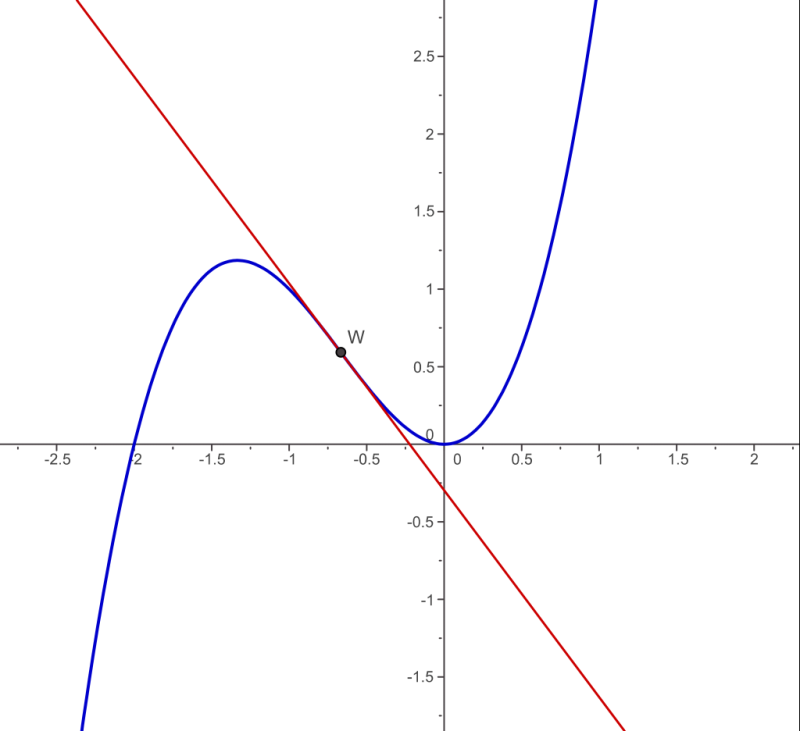

Graph of showing an inflection point where concavity changes. The bending of the curve illustrates the role of in shaping a function. Extra detail: this specific function is not required by the syllabus but helps visualize an inflection point. Source.

Concavity and Changing Rates

Concavity determines whether a graph bends upward or downward and thus whether the first derivative is increasing or decreasing.

A function with positive second derivative is concave up, meaning its slope becomes more positive as x increases.

A function with negative second derivative is concave down, meaning its slope becomes more negative as x increases.

Points where the second derivative changes sign may correspond to inflection points, locations where the curve changes its bending behavior.

These interpretations allow students to understand not only what a function is doing at a moment but also how that behavior is evolving.

Higher-Order Derivatives Beyond the Second

While the AP Calculus AB course rarely requires computing very high-order derivatives of complex functions, students must be able to interpret what these derivatives represent conceptually.

Higher-Order Derivative: Any derivative of order three or greater, obtained by repeatedly differentiating a function.

Higher-order derivatives refine the analysis of change:

The third derivative describes how the second derivative changes, connecting to how concavity itself evolves.

The fourth derivative and beyond can reveal deeper layers of variability, though their interpretations depend heavily on context.

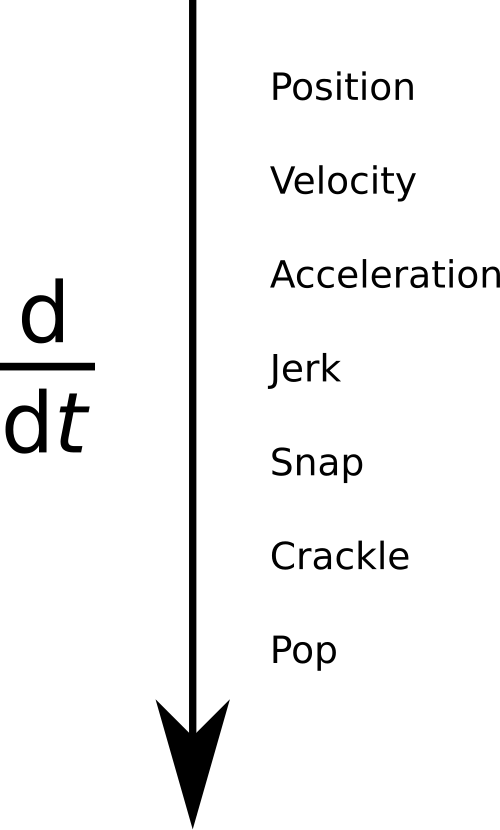

Interpreting Higher-Order Derivatives in Motion

Motion provides a natural setting for interpreting derivatives:

The position function describes location.

The first derivative gives velocity, explaining how position changes over time.

The second derivative gives acceleration, describing how velocity changes.

The third derivative, sometimes called jerk, describes how acceleration changes.

= velocity, the rate of change of position

= position function

A single sentence must occur here before any additional block appears.

= acceleration, the rate of change of velocity

= velocity

The third derivative, sometimes called jerk, describes how acceleration changes.

Diagram illustrating successive time derivatives from position through acceleration to jerk and beyond. Each level corresponds to differentiating once more with respect to time. Extra detail: derivatives beyond jerk appear for completeness but exceed AP Calculus AB requirements. Source.

These relationships highlight how each derivative adds a new layer of interpretation. Students should understand that motion is only one example; the same structure appears in economics, biology, and other fields.

Higher-Order Derivatives and Graphical Behavior

Higher-order derivatives connect deeply to graphical features:

The first derivative relates to slope and increasing or decreasing behavior.

The second derivative determines concavity and helps identify inflection points.

The third derivative can indicate how quickly concavity changes, providing insight into transitions between curvature behaviors.

Higher orders may refine understanding of how sharply or smoothly the graph changes shape.

These interpretations are essential for analyzing complex functions where direct visual inspection is insufficient. Higher-order derivatives thus serve as diagnostic tools for describing subtle behavior in a graph.

Higher-Order Derivatives in Real-World Modeling

Many real-world systems involve quantities that change in layered ways. Higher-order derivatives become meaningful in contexts such as:

Physics, where jerk and snap influence engineering design for vehicles or robotics.

Economics, where the second derivative can describe marginal acceleration of growth or decline.

Biology, where changing rates of population growth reflect environmental conditions or resource availability.

In these applications, higher-order derivatives clarify how responsive or stable a system is. A rapidly changing second derivative, for example, may signal instability or sharp transitions in the system’s behavior.

Recognizing the Importance of Interpretation

Interpreting higher-order derivatives requires more than computation. Students must connect mathematical expressions to meaningful descriptions:

Identify what each derivative represents in context.

Determine how changes in one derivative influence earlier ones.

Use the behavior of derivatives to justify conclusions about shape, motion, or application-specific outcomes.

Higher-order derivatives ultimately provide a structured way to describe increasingly refined layers of change, aligning directly with the AP focus on interpreting how earlier derivatives evolve across mathematical and applied settings.

FAQ

Higher-order derivatives describe how each preceding derivative is changing, allowing you to compare functions whose first and second derivatives show similar behaviour.

For example, if two functions share the same concavity, examining the third derivative can reveal differences in how rapidly that concavity changes.

This provides insight into the smoothness of transitions, the sharpness of bends, or the rate at which curvature evolves.

Some turning points occur where the first derivative is zero and the second derivative is close to zero or inconclusive.

In such cases, the third derivative can show whether the concavity is shifting rapidly enough to clarify the nature of the turning point.

It helps detect nuanced features such as flattening before a sharp rise or fall.

Higher-order derivatives reveal how quickly key rates are changing, letting you gauge whether a system is settling, oscillating, or destabilising.

A system is often considered more stable when:

• rates change smoothly

• acceleration and its higher derivatives do not fluctuate sharply

• changes diminish rather than amplify over time

Smooth curves typically have higher-order derivatives that remain continuous or change gradually.

Piecewise-defined or abruptly changing functions often show jumps, undefined values, or rapid oscillations in higher-order derivatives.

Examining these derivatives offers a structured way to identify hidden discontinuities or sharp transitions not immediately obvious in the graph.

They help determine whether acceleration trends will continue, level off, or reverse, influencing predictions about future movement.

For example:

• decreasing acceleration suggests velocity will approach a limiting value

• rapidly changing jerk can indicate discomfort or mechanical strain in engineered systems

• sustained negative higher derivatives may signal eventual slowing or stabilisation

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

A function f has a derivative f' that is increasing on the interval 0 < x < 5.

What does this indicate about the concavity of f on this interval, and what does it imply about the behaviour of f''?

(1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: States that f is concave up on the interval.

• 1 mark: States that f' increasing implies f'' is positive.

• 1 mark: Provides a correct interpretation, such as slopes of f becoming steeper or increasing.

(4–6 marks)

A particle moves along a line with position function s(t). The table below gives selected values of its acceleration a(t) and jerk j(t).

t: 1, 2, 3

a(t): 4, 3, 1

j(t): -1, -2, -3

(a) Describe how the velocity of the particle is changing on the interval 1 < t < 3.

(b) Explain how the sign of j(t) affects the acceleration, and what this means for the motion of the particle.

(c) State one real-world implication of a continually decreasing acceleration for the particle’s movement.

(4–6 marks)

(a)

• 1 mark: Identifies that acceleration is decreasing over the interval.

• 1 mark: Concludes that velocity is increasing but at a decreasing rate.

(b)

• 1 mark: States that negative jerk means acceleration is decreasing.

• 1 mark: Correctly explains that this decreasing acceleration slows the rate at which velocity increases.

(c)

• 1 mark: Gives a valid real-world implication, such as the particle gradually approaching a constant speed or experiencing reduced effectiveness of propulsion.