AP Syllabus focus:

‘If a continuous function has exactly one critical point on an interval and that point is a local maximum or minimum, then it is also the absolute extremum on that interval.’

When a continuous function has exactly one critical point on an interval, analyzing that point’s behavior allows us to determine whether it must serve as the absolute extremum.

Understanding the Role of a Single Critical Point

A central idea in analyzing extrema is the identification of points where the function’s derivative provides key structural information. When a function defined on an interval possesses exactly one critical point, and the function is continuous on that interval, the behavior of the function near that point becomes crucial in determining whether the extremum is absolute. This subsubtopic focuses on how continuity, differentiability, and local behavior combine to guarantee that this single interior point must also be the absolute maximum or absolute minimum on that interval.

Graph of on the closed interval , showing a single interior critical point where the graph has a local and absolute minimum. The endpoints lie above this minimum, illustrating how a unique critical point in a continuous function can determine an absolute extremum. This figure includes interval shading and labeled points consistent with standard calculus presentations. Source.

Critical Points and Their Significance

A critical point is a point in the domain where the derivative of a function is zero or undefined.

Critical Point: A point in the domain of where or does not exist.

This concept matters because extrema of differentiable functions occur only at critical points or endpoints.

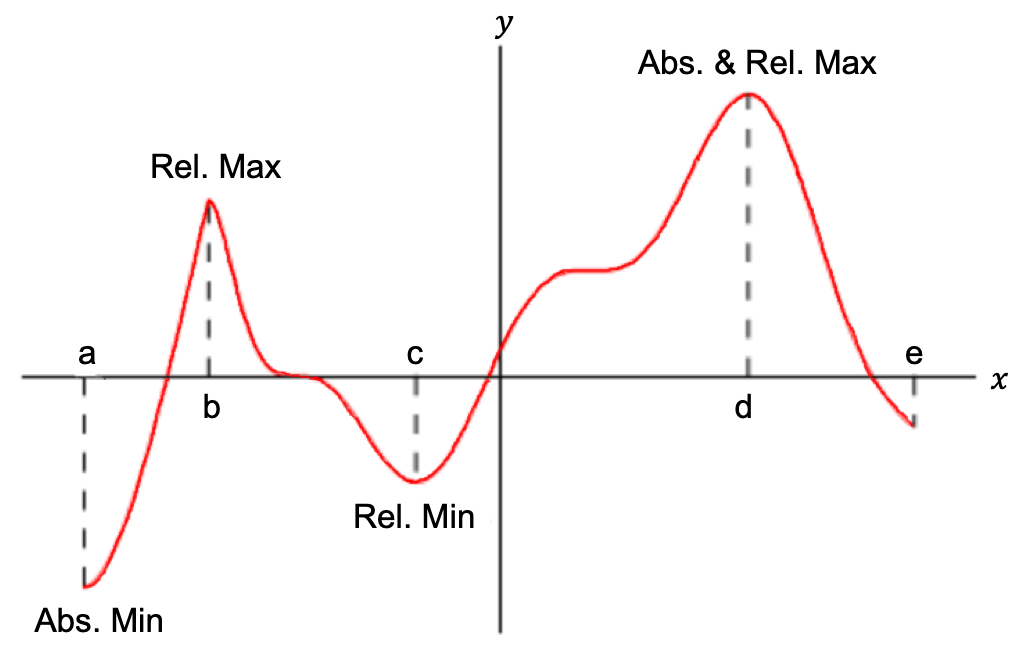

A continuous curve illustrates the distinction between local and global extrema, with labeled points indicating each type. This supports the idea that critical points can produce different categories of extrema. The diagram includes more extrema than required for the single-critical-point scenario but remains strictly relevant for understanding the hierarchy of extremal behavior. Source.

To ensure clarity in analysis, it is essential that the function be continuous over the interval of interest. Continuity prevents jumps, breaks, or asymptotes from disrupting the extremum structure, making it possible to compare function values reliably across the interval.

Why One Local Extremum Must Be Absolute

When a function has exactly one critical point within an interval, and the function’s continuity ensures smooth behavior with no missing values, a local extremum at that point cannot be merely relative. For instance, if the point is shown to be a local maximum, then around that point the function reaches a value greater than that of all sufficiently close nearby points. Because there are no other interior critical points where the function could reverse course, no other interior location can surpass it. The same reasoning applies to a single local minimum.

Using Derivative-Based Tests to Classify the Point

The identification of the single critical point is only the first step. The function’s behavior near that point must be classified using established derivative-based methods.

These tools include:

First Derivative Test, which examines sign changes in the derivative around the point.

Second Derivative Test, which uses curvature information to determine whether the point is a local minimum or maximum.

Local Extremum: A point where the function value is greater than or less than all nearby function values.

Once one of these tests confirms that the point is indeed a local extremum, the function’s continuity and the absence of other critical points allow us to extend this result to the entire interval.

A sentence or two explaining why this structure matters helps reinforce the conceptual connection between local and global behavior. Essentially, the lack of other turning points ensures that the function cannot rise above a local maximum or sink below a local minimum anywhere else in the interval.

Continuity and Its Guarantee of Absolute Behavior

Continuity over a closed interval is particularly valuable because it ensures the function attains both a greatest and least value somewhere in the interval.

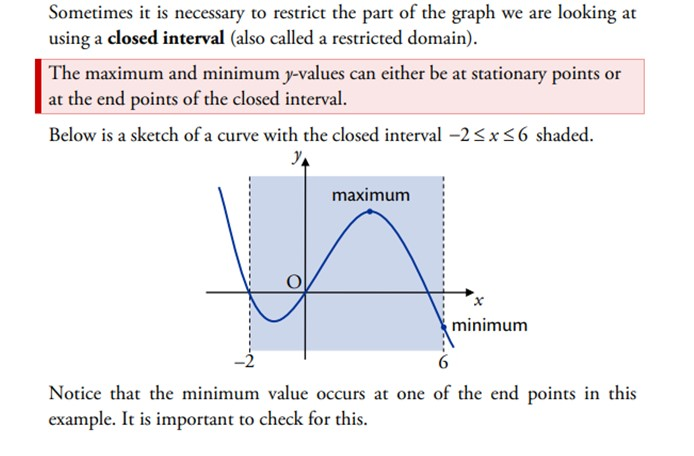

The graph shows a function defined on a shaded closed interval, with a maximum at an interior stationary point and a minimum at an endpoint. This visually reinforces the necessity of continuity on a closed interval for ensuring absolute extrema. The additional shading and endpoint markers provide helpful structural clarity consistent with standard calculus conventions. Source.

When there is exactly one critical point, the question becomes whether an endpoint could exceed a locally extreme value at that point. Because the function’s shape is constrained by having only that one place where the derivative changes direction or fails to exist, the endpoint values must remain on one side of the function’s behavior at the critical point.

If the point is a local maximum, the endpoints cannot exceed it without introducing an undiscovered critical point contradicting the assumption of uniqueness. If the point is a local minimum, then the endpoints likewise cannot fall below it for the same reason.

Situations Where This Principle Applies

The principle is especially useful when analyzing functions with smooth, predictable behavior, such as polynomials on closed intervals. It also applies to many rational and transcendental functions, provided the continuity and single critical point conditions are met. Students should note that discontinuities, sharp corners, or undefined intervals invalidate the reasoning, because they can introduce boundary behaviors or abrupt changes inconsistent with the assumption of smoothness.

Moreover, functions defined on open intervals require more careful handling. If an interval lacks endpoints or excludes its boundary values, an absolute extremum may fail to exist even when a local extremum is present. This distinction reinforces the necessity of checking interval type before drawing global conclusions.

Connecting Local Information to Global Conclusions

Understanding this subsubtopic reinforces the broader AP Calculus AB theme that local derivative information often controls global function behavior. A single, verified local extremum on a continuous interval becomes the definitive absolute extremum because the derivative structure prevents any further deviations in shape that would generate another candidate point.

This conceptual bridge between local analysis and global outcome is key to developing strong problem-solving intuition in calculus and highlights the power of the derivative as a tool for studying entire functions based on limited critical data.

FAQ

A fast way to identify this is to confirm two things: the function is continuous on a closed interval, and there is exactly one interior critical point.

If that critical point is known to be a local extremum, then no other competing turning point exists, so it must be absolute. Endpoints do not overturn this conclusion unless their function values contradict the local behaviour, which continuity prevents in this scenario.

No. On an open interval, the function might not achieve its greatest or least values at all, even if a local extremum exists.

An interior extremum may fail to be an absolute extremum because the endpoints are not included and could be approached with larger or smaller values.

Yes, but only if the unique critical point is not an extremum (for example, a point of inflection).

In that case, the function values at the endpoints may exceed or fall below the interior value. The key condition for the subsubtopic’s result is that the critical point is a local maximum or minimum.

The result still holds as long as the point is a genuine local extremum and the function remains continuous on the interval.

Such a point might come from a cusp or corner. If it is the sole location where the function changes direction, and continuity prevents other extremal behaviour, it becomes the absolute extremum.

Without continuity, jumps or breaks could introduce larger or smaller values away from the critical point, creating absolute extrema elsewhere.

Continuity ensures the function’s behaviour cannot ‘skip’ over values, meaning a verified local extremum cannot be undermined by an abrupt discontinuity.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A function f is continuous on the closed interval [1, 7]. Its derivative exists on (1, 7) and has exactly one zero at x = 4. The value f(4) is a local minimum.

Explain why f(4) must also be the absolute minimum of f on the interval [1, 7].

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: States that f(4) is the only interior critical point.

• 1 mark: States that the function is continuous on a closed interval, so it must attain absolute extrema.

• 1 mark: Concludes that because the only critical point is a local minimum, and no other turning points exist, f(4) must be the absolute minimum.

Total: 3 marks.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A function g is continuous on the closed interval [–3, 5] and differentiable on (–3, 5).

The derivative g' has exactly one critical point at x = 1, where g'(1) = 0. The Second Derivative Test shows that g''(1) is negative.

In addition, g(–3) = 9, g(1) = –2, and g(5) = 4.

(a) State what the sign of g''(1) indicates about the nature of g at x = 1.

(b) Using all the given information, determine the absolute maximum and the absolute minimum values of g on [–3, 5]. Justify your answer.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(a)

• 1 mark: States that g''(1) < 0 implies a local maximum at x = 1.

(b)

• 1 mark: Evaluates all candidates: the endpoints x = –3 and x = 5, and the critical point x = 1.

• 1 mark: Identifies the absolute maximum value as 9 at x = –3 (the largest function value).

• 1 mark: Identifies the absolute minimum value as –2 at x = 1 (the smallest function value).

• 1 mark: Provides correct justification linking the unique critical point and continuity on the closed interval to the existence and location of the absolute extremum.

Total: 6 marks.