AP Syllabus focus:

‘Given information about a function’s behavior, decide whether a left, right, midpoint, or trapezoidal approximation gives an underestimate or overestimate of the integral.’

These notes explain how function behavior determines whether common numerical integration methods produce overestimates or underestimates when approximating definite integrals over fixed intervals graphically interpreted.

Understanding Overestimates and Underestimates

When approximating the value of a definite integral, numerical methods replace the exact area under a curve with simpler geometric shapes. Depending on how these shapes compare to the actual curve, the approximation may be larger or smaller than the true integral value. Identifying whether an approximation is an overestimate or underestimate relies on understanding the behavior of the function over the interval.

Overestimate: An approximation whose numerical value is greater than the exact value of the definite integral.

A normal sentence must separate definition blocks, and this sentence emphasizes that the comparison is always made relative to the true accumulated area.

Underestimate: An approximation whose numerical value is less than the exact value of the definite integral.

The key idea for this subtopic is qualitative reasoning: students use graphical and behavioral information, not computation, to determine the direction of error.

Role of Function Behavior

The accuracy direction of Riemann sum and trapezoidal approximations depends on two major characteristics of the function on the interval:

Increasing or decreasing behavior

Concavity (concave up or concave down)

Increasing function: A function whose values rise as the input increases over an interval.

Always consider whether the function’s graph lies mostly above or below the rectangles or trapezoids used in the approximation. Visual reasoning is essential.

Monotonic Behavior and Left/Right Riemann Sums

For left and right Riemann sums, the determining factor is whether the function is increasing or decreasing.

For an increasing function:

A left Riemann sum uses smaller function values on each subinterval.

A right Riemann sum uses larger function values on each subinterval.

As a result:

Left Riemann sums give an underestimate.

Right Riemann sums give an overestimate.

For a decreasing function, this relationship reverses:

Left Riemann sums give an overestimate.

Right Riemann sums give an underestimate.

This reasoning follows directly from comparing rectangle heights to the curve on each subinterval.

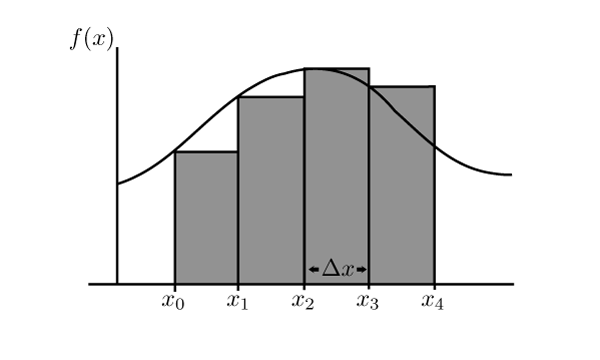

Left-hand Riemann sums approximate a definite integral by using rectangle heights determined at the left endpoints of each subinterval. For an increasing function, these rectangles lie below the graph, so the total area is an underestimate of the true integral. The image focuses only on left sums for a positive function and does not include midpoint, right, or trapezoidal approximations. Source.

Midpoint Rule and Function Shape

The midpoint Riemann sum uses the function value at the center of each subinterval. Whether this method overestimates or underestimates depends on the function’s concavity, not whether it is increasing or decreasing.

Concave up: A function whose graph curves upward, with tangent lines lying below the graph.

If a function is concave up over an interval:

The midpoint rectangles tend to lie below the curve.

The midpoint approximation is an underestimate.

If a function is concave down:

The midpoint rectangles tend to lie above the curve.

The midpoint approximation is an overestimate.

This happens because midpoint values reflect the curvature of the graph rather than its endpoint behavior.

Trapezoidal Rule and Concavity

The trapezoidal rule approximates area using trapezoids formed by connecting endpoints of the graph over each subinterval. The direction of error depends entirely on concavity.

For a concave up function:

Trapezoids lie mostly above the curve.

The approximation is an overestimate.

For a concave down function:

Trapezoids lie mostly below the curve.

The approximation is an underestimate.

This relationship contrasts directly with the midpoint rule, making concavity especially important when comparing methods.

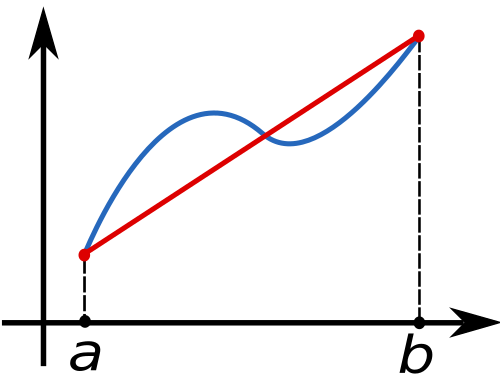

This diagram illustrates the trapezoidal rule, where each subinterval under the curve is replaced by a trapezoid whose nonparallel sides follow the function. The collection of shaded trapezoids approximates the total area under the curve and thus the definite integral. The image shows only the geometric setup without presenting any additional numerical methods. Source.

Comparing Approximation Methods Conceptually

All numerical approximations aim to estimate the same quantity: the value of a definite integral.

= Exact accumulated change

= Rate or function value at input

= Interval endpoints

However, different methods construct different geometric approximations:

Left and right sums depend on endpoint values.

Midpoint sums depend on central values.

Trapezoidal sums depend on linear interpolation between endpoints.

Understanding the function’s graph allows students to determine whether these shapes lie above or below the curve without calculation.

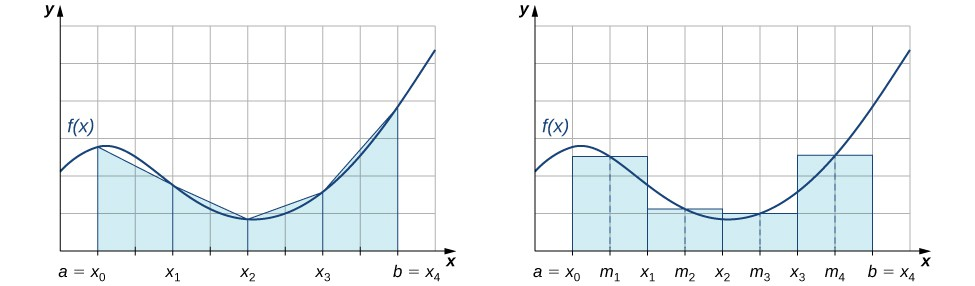

The left graph shows trapezoids under a nonnegative function, while the right graph shows midpoint rectangles for the same partition. Together they highlight how using endpoints versus midpoints changes the positions of approximating shapes relative to the curve, explaining systematic overestimates and underestimates. The image comes from a broader numerical integration discussion but focuses specifically on midpoint and trapezoidal approximations relevant to this subsubtopic. Source.

Key Reasoning Strategies for AP Calculus AB

When deciding whether an approximation is an overestimate or underestimate, follow these steps:

Identify whether the function is increasing or decreasing.

Identify whether the function is concave up or concave down.

Match the function behavior to the approximation method used.

Compare the position of the approximation shapes relative to the curve.

This reasoning-based approach aligns directly with AP Calculus AB expectations and emphasizes conceptual understanding over numerical computation.

FAQ

Changing the width of subintervals does not change the direction of error; it only changes the magnitude of the error. If a method gives an overestimate for a particular function behaviour, it will continue to do so regardless of subinterval width.

However, smaller subintervals reduce the overall error because the approximation follows the curve more closely. Wider subintervals amplify the difference between the approximating shapes and the actual curve.

Yes, but only if the function’s concavity changes somewhere in the interval. The midpoint rule’s direction of error depends entirely on concavity.

If the function is concave up on part of the interval and concave down on another, the midpoint rectangles may lie partly above and partly below the curve. The net error could therefore be smaller or unpredictable without analysing concavity piecewise.

Left and right sums rely solely on function values at interval endpoints, so only increasing or decreasing behaviour impacts the relative height of rectangles.

The trapezoidal rule, however, uses a straight line between endpoints. This line:

Cuts above the graph when the curve is concave up

Falls below the graph when the curve is concave down

Thus, curvature determines its direction of error.

Yes, but the interpretation changes relative to the signed area. The shapes used in the approximation (rectangles or trapezoids) are compared to the curve’s position below the x-axis.

For example, if the function is negative and increasing, a left sum may overestimate the integral because the rectangles lie above the curve toward zero, making the numerical value less negative than the true integral.

Graphical reasoning focuses on geometric placement of rectangles or trapezoids relative to the curve. To decide quickly:

Identify whether the function is increasing or decreasing.

Observe the curve’s concavity.

Visualise the shapes: Do they sit above or below the curve?

This method allows students to judge overestimates or underestimates purely by examining the graph’s shape and behaviour.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A function f is increasing and positive on the interval [2, 6]. A student uses a left Riemann sum with four equal subintervals to approximate the value of the integral of f over this interval.

(a) State whether the student’s approximation is an overestimate or an underestimate.

(b) Give a brief reason for your answer.

Question 1

(a) 1 mark: States that the left Riemann sum is an underestimate.

(b) 1–2 marks: Explains that for an increasing function, the left endpoint values are smaller than the actual function values across each subinterval, so the rectangles lie below the graph.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A function g is decreasing and concave up on the interval [1, 5]. A right Riemann sum with five equal subintervals and a trapezoidal approximation are both used to estimate the integral of g over this interval.

(a) Determine whether the right Riemann sum gives an overestimate or an underestimate.

(b) Determine whether the trapezoidal approximation gives an overestimate or an underestimate.

(c) Explain, with reference to the behaviour of g, why the direction of error differs between these two numerical methods.

Question 2

(a) 1–2 marks: States that the right Riemann sum is an underestimate. For a decreasing function, the right endpoint values are smaller than the left endpoint values and lie below the curve.

(b) 1–2 marks: States that the trapezoidal approximation is an overestimate. For a concave up function, the line segments connecting the endpoints lie above the graph.

(c) 1–2 marks: Clearly explains that monotonic behaviour (decreasing) affects the accuracy of right sums, while concavity (concave up) determines whether the trapezoidal method produces an overestimate, causing the two methods to differ in their direction of error.