AP Syllabus focus:

‘Specific applications of exponential differential equations include motion along a line and models of population growth or radioactive decay, where students determine and interpret general and particular solutions.’

Applying Exponential Models to Real-World Contexts

Exponential differential equations model quantities whose rate of change is proportional to their current value, allowing students to interpret growth or decay across diverse real-world situations.

Understanding Exponential Modeling in Context

Real-world systems often change at a rate dependent on their present amount, making exponential models central to interpreting natural, physical, and social processes. When a situation states that a quantity grows or decays proportionally to its size, it is modeled by a first-order differential equation of the form . This structure links the behavior of the dependent variable to the constant rate factor that governs growth or decay.

Exponential Model: A model in which the rate of change of a quantity is proportional to the quantity itself, typically represented by .

Because proportional change is common in nature, exponential models appear in multiple AP-required contexts, including population growth, radioactive decay, and motion along a line. Each context interprets the variables uniquely but relies on the same mathematical framework.

General Solutions in Real-World Modeling

Solving an exponential differential equation provides a family of functions representing all possible behaviors consistent with the model. For , the general solution takes the form , where is an arbitrary constant representing initial size.

= Quantity as a function of time

= Initial value constant

= Growth or decay constant

= Time

This general solution forms the basis for interpreting particular solutions once additional information is supplied. In applied settings, the meaning of each parameter must be tied directly to the scenario.

A sentence of normal text ensures conceptual continuity before introducing additional structured details.

For an exponential model satisfying , the general solution contains the arbitrary constant , representing all functions whose graphs have the same shape but may start at different values.

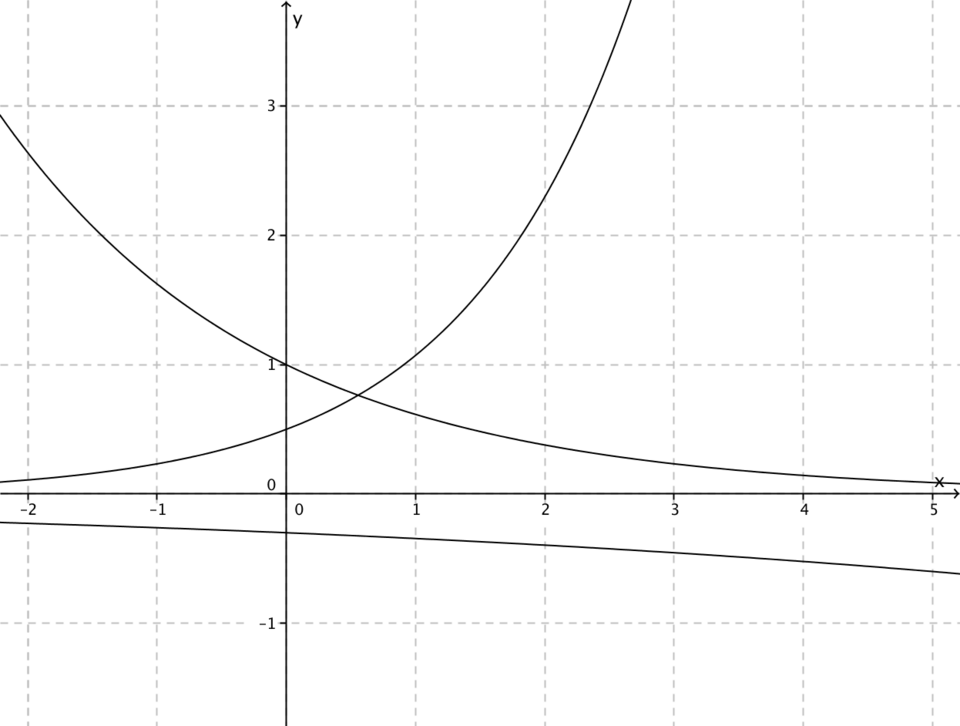

A set of exponential function graphs illustrating how changing parameters produces different growth curves. Each curve has the form , all passing through but increasing at different rates. The image includes specific functions beyond the AP syllabus but remains consistent with families of exponential solutions. Source.

Interpreting Particular Solutions in Context

A particular solution arises when the model includes enough information—usually an initial condition—to determine a unique function. In applications, interpreting the solution requires understanding:

what the dependent variable represents

what time measures

the meaning and units of and

whether the situation describes growth () or decay ()

Initial Condition: A specified value of the dependent variable at a particular time that determines a unique particular solution.

Interpreting these components helps translate the mathematical formula into statements about real-world behavior. A particular solution describes exactly how the modeled quantity evolves over time for the given scenario, rather than the full family of possible behaviors.

Population Growth as an Exponential Application

When modeling population growth, AP Calculus AB students examine situations where a population increases proportionally to its current size. This leads to equations of the form , where represents population and captures the relative growth rate. Key interpretive tasks include:

identifying as the dependent variable and time as the independent variable

connecting to the percentage growth rate

understanding that describes how the population evolves from the initial amount

Population problems typically involve growth, so students interpret increasing functions and accelerating change as time progresses.

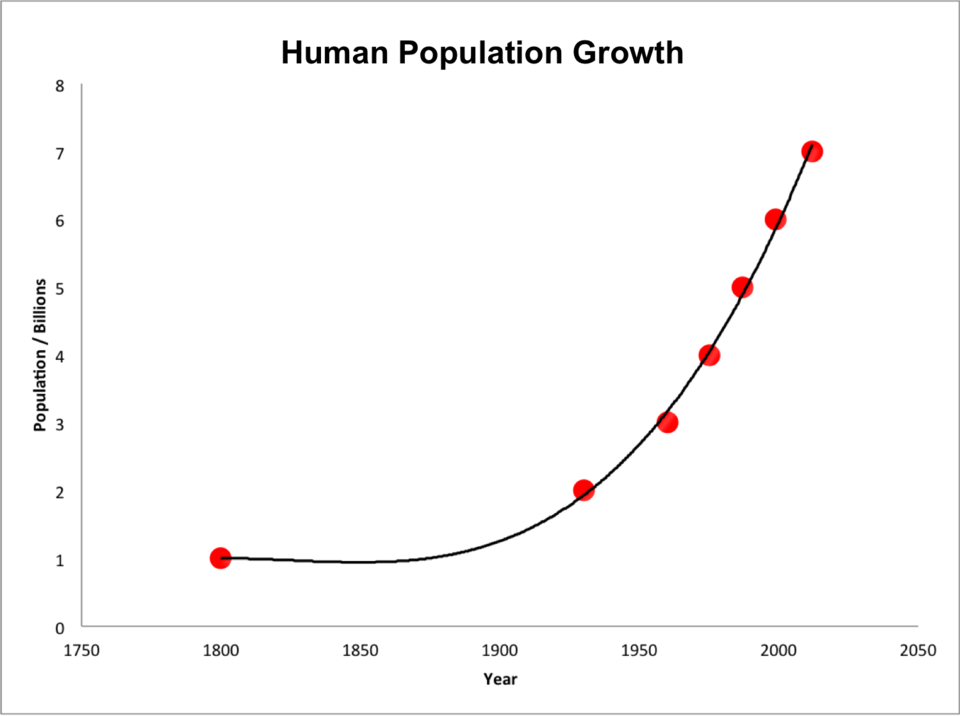

This graph shows estimated world population versus time, forming a curve that steepens dramatically in the twentieth century. Its shape is consistent with an exponential model , where the rate increases with population size. Although it includes detailed historical data, this added information supports the AP goal of interpreting population growth as an exponential process. Source.

Radioactive Decay as an Exponential Application

Radioactive decay provides a contrasting example involving exponential decay rather than growth. The quantity of a radioactive substance decreases at a rate proportional to the amount present, leading to with . Interpretive elements include:

recognizing that the negative constant produces a decreasing exponential

associating the model with physical behaviors such as half-life

interpreting as expressing how the amount declines over time

Students must articulate how the decay constant affects the steepness and long-term behavior of the curve, noting that the function approaches zero without ever becoming negative.

Motion Along a Line and Exponential Behavior

Some motion scenarios also rely on exponential differential equations, especially when a velocity or displacement changes proportionally to its current value. In these cases, students analyze:

what physical quantity corresponds to the dependent variable

how proportionality influences acceleration or velocity

the meaning of parameters once rewritten in exponential form

These interpretations help connect calculus concepts to physical reasoning about motion.

Interpreting the Meaning of Parameters

Across all real-world contexts, the parameters in an exponential solution carry specific meanings:

represents the initial state of the system.

determines long-term behavior; its sign indicates growth or decay, while its magnitude affects how rapidly change occurs.

is the independent variable marking the progression of the modeled process.

Students must clearly distinguish between mathematical structure and contextual meaning to draw correct conclusions.

Using Models to Understand Real-World Change

Applying exponential differential equations in real-world contexts requires students to articulate how the formula, constants, and derivative expression describe the behavior of the modeled quantity. Whether examining population expansion, radioactive decay, or motion along a line, the focus is on interpreting the general solution and explaining how a given particular solution fits the situation described by the initial information.

FAQ

Look for wording that describes the rate of change as proportional to the current amount. Phrases such as “increases by a constant percentage” or “decreases at a rate proportional to what remains” signal an exponential model.

Growth occurs when the quantity increases at a proportional rate, while decay occurs when a proportional rate reduces the amount over time.

Many systems change relative to their current size. This makes proportional change a natural assumption.

Common reasons include:

• feedback mechanisms, such as reproduction increasing population size

• decay processes where the chance of breakdown depends on the amount present

• financial or economic systems with compounding effects

The steepness of the curve indicates the magnitude of the constant. A larger positive value produces faster growth; a more negative value produces faster decay.

You can also examine doubling or halving behaviour. Short doubling times suggest larger growth constants, while short halving times suggest a stronger decay rate.

Time should match the units given in the context. For example, if data are collected per year, the model uses years as the time variable.

In most real-world applications, time represents how long the phenomenon has been occurring, starting from an initial reference point such as the beginning of an experiment or measurement period.

Exponential models assume unlimited proportional change, which rarely holds indefinitely.

Limitations include:

• resource shortages reducing growth

• physical or environmental constraints

• external influences such as policy changes or technology

• measurement errors or incomplete data

These factors can cause deviations from ideal exponential behaviour over long periods.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A population P(t) grows according to the differential equation dP/dt = 0.04P.

At time t = 0, the population is 500.

State a particular solution for P(t) and explain what the constant 0.04 represents in this context.

Question 1 (3 marks)

• 1 mark: States a correct particular solution, e.g. P(t) = 500e^(0.04t).

• 1 mark: Identifies that 0.04 represents the proportional growth rate or percentage rate of increase per unit time.

• 1 mark: States that this constant determines how rapidly the population increases.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A radioactive substance decays at a rate proportional to the amount present.

The mass M(t), in grams, satisfies the differential equation dM/dt = kM, where k is a negative constant.

At time t = 0, the substance has a mass of 120 g. After 10 years, the mass has decreased to 90 g.

(a) Write down the general solution for M(t).

(b) Use the information given to determine the value of k.

(c) Using your value of k, find the mass remaining after 25 years.

(d) Briefly explain how your solution reflects the long-term behaviour of the substance.

Question 2 (6 marks)

(a)

• 1 mark: States a correct general solution, e.g. M(t) = Ce^(kt).

(b)

• 1 mark: Substitutes initial condition to give C = 120.

• 1 mark: Uses M(10) = 90 to form the equation 90 = 120e^(10k).

• 1 mark: Solves for k correctly, e.g. k = (1/10) ln(90/120), a negative value.

(c)

• 1 mark: Substitutes t = 25 into M(t) = 120e^(kt) using their value of k.

• 1 mark: Correctly evaluates the mass (allow follow-through).

(d)

• 1 mark: States that the mass decreases towards zero but never becomes negative, reflecting exponential decay.