AP Syllabus focus:

‘Given initial values or additional data points, students solve for unknown constants in exponential solutions, using equations like y = y₀e^{kt} to fit a model to contextual information.’

This subsubtopic focuses on determining unknown parameters in exponential differential-equation models by interpreting contextual data, ensuring students can accurately connect observed values to the form of an exponential solution.

Using Data to Determine Parameters in Exponential Models

A differential equation of the form describes exponential behavior, meaning the rate of change of a quantity is proportional to its current amount. Solving this differential equation produces a general exponential model that allows AP Calculus AB students to use real-world data to determine unknown constants and fully specify the model for a given situation.

When working with exponential models, AP students must identify how numerical data—such as initial values or additional observed points—allow us to solve for the constants that define the solution curve. These constants typically include the initial amount and the growth or decay constant, both of which give the model its specific shape and behavior over time.

Understanding the Exponential Model Form

The standard exponential solution derived from is written as , where constants must be determined from contextual information.

= Quantity at time

= Initial value of the quantity (unit depends on context)

= Growth/decay constant (units of )

= Independent variable, typically time

This formula expresses how a quantity evolves exponentially and provides the structure needed to incorporate given data.

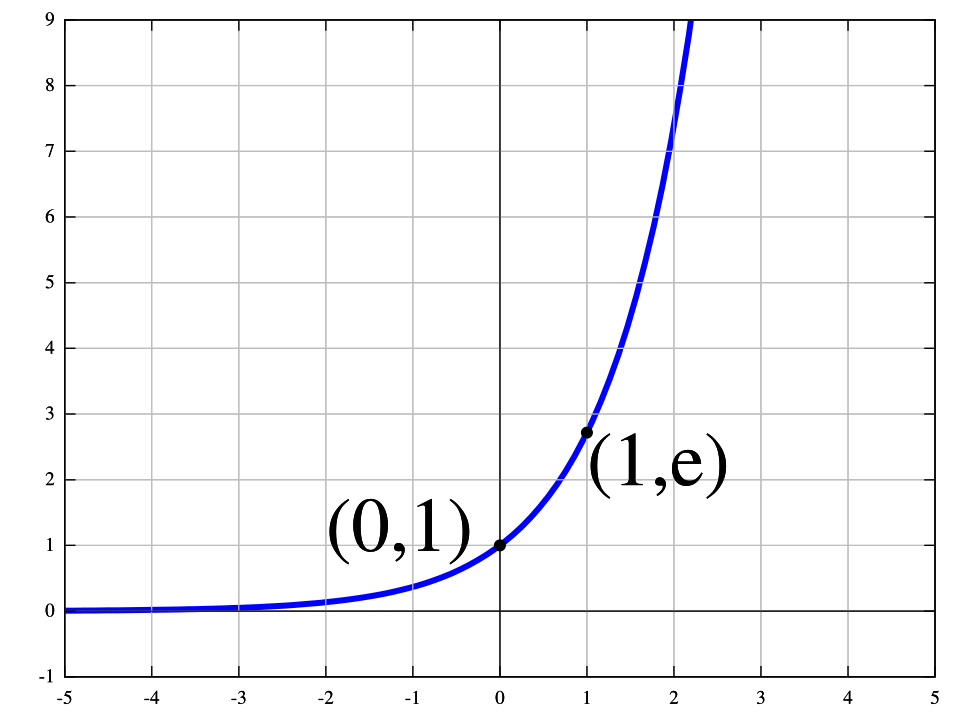

This graph shows the natural exponential function on the interval −5 to 5, illustrating the characteristic shape of exponential growth. It reinforces the structure of the model when . The image contains only core graph features relevant to AP Calculus AB. Source.

A sentence here to maintain spacing before any additional definitions.

Identifying Known and Unknown Parameters

Students often encounter exponential models where either , , or both are unknown. To determine these constants, the model must be paired with contextual data, such as:

An initial condition

A value of the quantity at a later time

Multiple measured data points

Descriptions indicating growth or decay behavior

When the initial condition is explicit, determining is straightforward. Additional data, such as another point on the function, then allow for determining .

Interpreting Initial Conditions

An initial condition is information that specifies the value of the function at a particular time. It is most commonly expressed as a statement like “when , the quantity is .”

Initial Condition: A given value of the dependent variable at a specified value of the independent variable that allows selection of a unique solution from a family of functions.

Initial conditions anchor the model at a specific point, ensuring the mathematical equation aligns with observed or given starting information.

A sentence here to separate definition and upcoming content.

Using Additional Data Points to Determine Constants

When only one condition such as is available, the parameter remains unknown. To find , students use an additional data point, meaning another pair of values from the situation. The exponential model must satisfy this second condition, allowing the unknown constant to be computed algebraically.

To determine parameters using data, students typically follow this process:

Identify all known quantities from the context.

Substitute known values into the exponential model.

Use an additional data point to produce an equation in the unknown parameter.

Solve algebraically for or as needed.

Rewrite the model with the determined constant(s) to produce a complete exponential solution.

These steps ensure that the model fits the provided measurements and reflects the real-world behavior described.

Connecting Parameter Values to Model Behavior

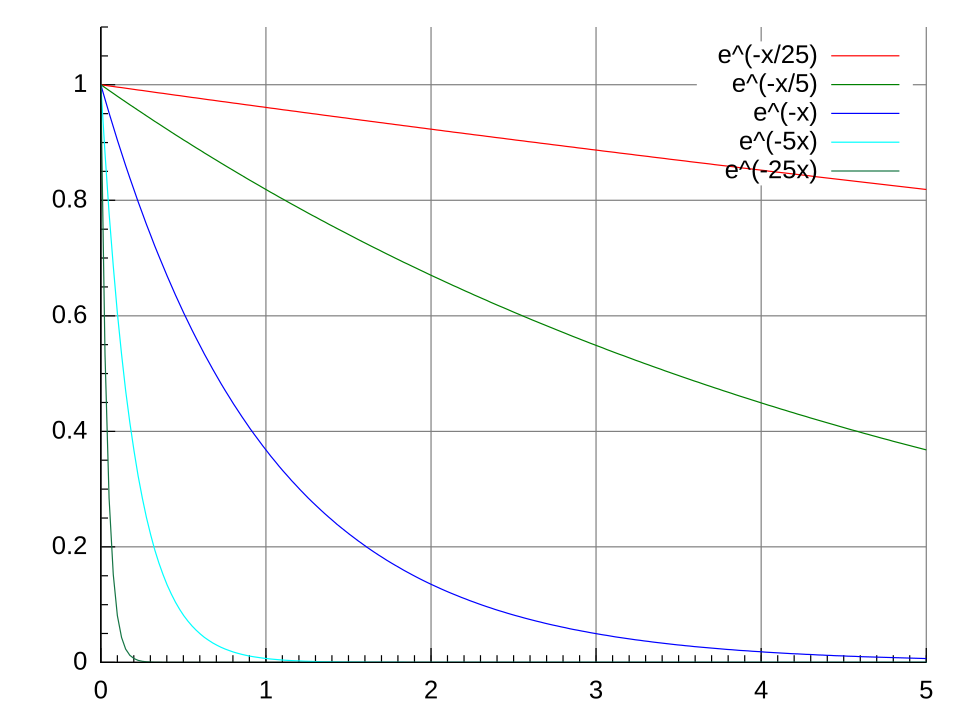

Once constants such as and are determined, students must understand how these values shape the solution curve. The constant determines where the graph begins, while governs the model’s growth or decay. Specifically:

If , the model represents exponential growth.

If , the model represents exponential decay.

The magnitude of influences how quickly the quantity increases or decreases.

This diagram shows multiple exponential decay functions, highlighting how different values of the constant affect the rate at which the quantity decreases. It illustrates that more negative values produce faster decay. The presence of multiple curves adds comparison detail but remains aligned with understanding parameter effects in exponential models. Source.

Knowing the effect of is essential because many contextual problems emphasize interpreting model behavior once parameters have been found.

Importance of Parameter Determination in Context

Determining parameters from data ensures that an exponential model accurately reflects the situation it describes. Students must not only compute constants but also interpret them meaningfully. For example, always represents the “starting value” of the quantity, and measures the rate at which the quantity grows or shrinks.

To find , students use an additional data point, meaning another pair of values from the situation.

This scatter plot illustrates how real-world data often appear as discrete points rather than a continuous curve. Such measured values at different times could be used to determine parameters like and in an exponential model. The image is generic and not tied to a specific exponential function, adding slight extra detail beyond the syllabus. Source.

This subsubtopic reinforces the connection between differential equations, exponential solution forms, and real-world modeling. By learning how to extract parameters from provided data points, students build the skill of aligning mathematical expressions with the behaviors they represent.

FAQ

A situation is usually appropriate for exponential modelling when the rate of change depends directly on the current value of the quantity.

This often appears in contexts involving proportional growth or decay.

Typical indicators include:

• Percent increases or decreases per unit time

• Constant relative growth rather than constant absolute growth

• Situations where doubling or halving times are meaningful

Data points that are spaced sufficiently far apart tend to give more stable estimates of k because small measurement errors have a reduced effect on the calculated growth rate.

It is also beneficial when:

• The data are measured under similar conditions

• The initial value is known precisely

• The quantity being measured changes noticeably over the interval

Units directly influence the interpretation of k, as it is always measured per unit of the independent variable.

If time is in hours, then k represents growth or decay per hour; if time is in years, k represents growth or decay per year.

Incorrect unit handling can produce misleading parameter values or an incorrectly shaped model.

The exponential model itself requires the quantity modelled to remain positive.

However, a negative time value (for example, t = -3) is acceptable because it merely refers to a point before the chosen starting time.

A negative value for the dependent variable is not valid, as exponential functions never output negative values.

If the context produces negative measurements, a different model should be used.

Simple checks can confirm that the model behaves as expected:

• Substitute both data points back into the completed model to ensure they are satisfied.

• Check whether the sign of k matches the narrative: growth should give k positive, decay k negative.

• Examine whether the predicted values align reasonably with known trends or limits from the context.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A quantity Q(t) grows exponentially and satisfies the model Q(t) = Q0 e^(kt).

Given that Q(0) = 120 and Q(3) = 180, determine the value of the constant k.

Give your answer correct to three decimal places.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: Substitutes values into the model to form the equation 180 = 120 e^(3k).

• 1 mark: Rearranges to obtain e^(3k) = 3/2 and solves for k.

• 1 mark: Correct final value k ≈ 0.135 (accept answers between 0.134 and 0.136).

Total: 3 marks.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A population P(t) is modelled by the differential equation dP/dt = kP, where k is a constant.

It is known that P(0) = 50.

After 10 years, the population has increased to 80.

(a) Use the given information to determine the values of P0 and k in the exponential model P(t) = P0 e^(kt).

(b) Hence write down the particular solution for P(t).

(c) Using your model, find the time at which the population first reaches 120.

Give your answer to the nearest year.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(a)

• 1 mark: Identifies P0 = 50 from the initial condition P(0) = 50.

• 1 mark: Substitutes P(10) = 80 into the model to form 80 = 50 e^(10k).

• 1 mark: Solves correctly for k to obtain k ≈ 0.047 (accept 0.046–0.048).

(b)

• 1 mark: States the correct particular solution P(t) = 50 e^(0.047t).

(c)

• 1 mark: Sets up 120 = 50 e^(0.047t).

• 1 mark: Solves for t to obtain t ≈ 18 (accept 17–19).

Total: 6 marks.