AP Syllabus focus:

‘Students interpret statements such as “the rate of change of a quantity is proportional to the quantity itself” by writing differential equations of the form dy/dt = ky to model exponential growth or decay.’

Exponential differential equations appear frequently in real-world modeling, linking changing quantities to growth or decay patterns. This subsubtopic develops the skill of translating contextual descriptions into differential equations.

Understanding Verbal Descriptions that Indicate Exponential Change

When interpreting verbal statements, AP Calculus AB students must recognize when a situation implies exponential growth or exponential decay. A typical description signals that a quantity changes at a rate tied directly to its current amount. This relationship reveals important structure in the underlying differential equation.

A common verbal cue is the phrase “rate of change is proportional to the quantity itself.” The word proportional indicates that the derivative is a constant multiple of the current value of the dependent variable. Because proportionality is central to exponential modeling, it is essential to articulate precisely what the phrase communicates mathematically.

Proportional relationship: A relationship in which one quantity is a constant multiple of another, written as , where is the constant of proportionality.

Such proportional descriptions appear across many contexts—population growth, radioactive decay, and other processes where change accelerates or slows depending on current levels.

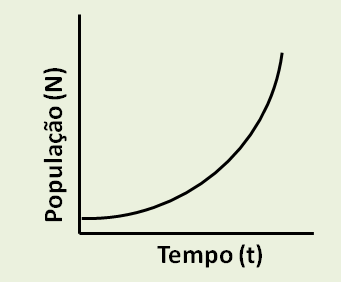

This graph shows an exponentially increasing population over time , illustrating the qualitative behavior associated with differential equations of the form when . As time passes, the curve steepens, reflecting how the rate of change increases when the quantity itself is larger. The axis labels are in Portuguese, but the mathematical behavior remains fully aligned with AP Calculus AB exponential growth models. Source.

Identifying Dependent and Independent Variables from Context

Before writing a differential equation, students must determine which quantity depends on another. In exponential models, the dependent variable typically represents the evolving quantity, while the independent variable generally represents time.

To interpret a verbal statement effectively, identify:

What quantity is changing.

What variable describes the passage of time or another driving factor.

How the rate of change relates to the current state of the quantity.

Once this structure is clear, the appropriate symbolic notation follows naturally. Students then express the derivative of the dependent variable with respect to the independent variable and match it to the described proportional behavior.

Translating Proportional Change into Derivative Notation

Verbal descriptions often use everyday language rather than mathematical terminology. To move from English sentences to mathematical form, students must recognize the equivalent symbolic expressions.

Key phrases that typically correspond to exponential differential equations include:

“Rate of change is proportional to the amount present.”

“Changes at a rate directly proportional to its size.”

“Decreases at a rate proportional to the current value.”

“Increases at a rate proportional to the quantity.”

Each of these statements implies that the derivative equals a constant multiplied by the function itself. The constant may represent a growth rate (positive) or decay rate (negative).

= Dependent variable representing the quantity modeled

= Independent variable, usually time

= Constant of proportionality (units depend on context)

This differential equation expresses the essential meaning of proportional change: the slope of the solution curve at any time depends on the value of the function at that moment. After forming this equation, the rest of the analysis—solving or interpreting—relies entirely on the model expressed.

A sentence such as “the amount of a substance decreases at a rate proportional to its mass” would therefore lead directly to the same differential equation form, although with . The sign of the constant determines whether the process represents growth or decay.

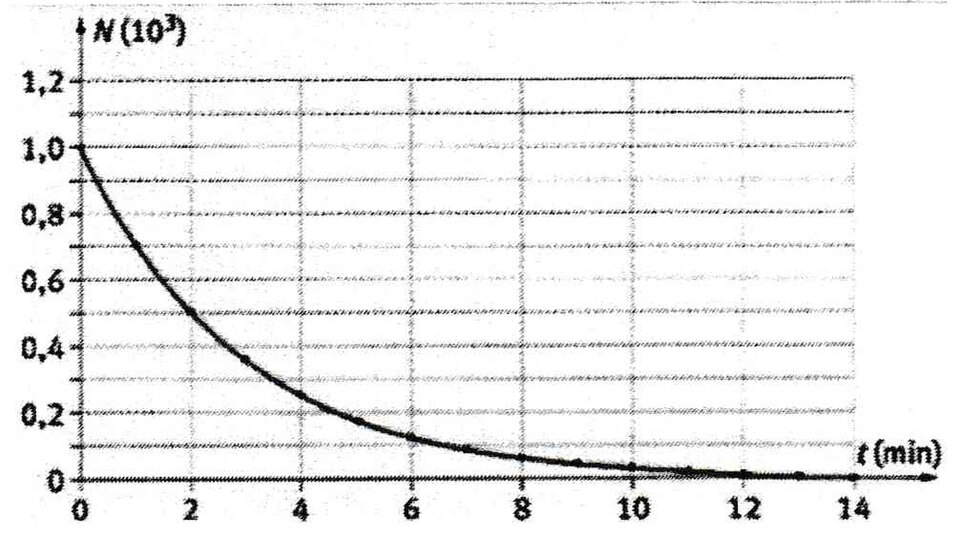

This figure displays an exponentially decreasing quantity over time, characteristic of a decay model such as with . The curve drops steeply at first and then gradually levels toward zero, highlighting that the magnitude of the rate of change is greatest when more material is present. The half-life markings offer extra detail beyond the AP syllabus, but remain consistent with the core idea of exponential decay in differential equation modeling. Source.

Distinguishing Growth and Decay from Verbal Indicators

The presence of the word increases or grows usually signals exponential growth, implying a positive proportionality constant. Conversely, wording such as decreases, decays, or diminishes typically indicates exponential decay, where the proportionality constant is negative.

Students should evaluate:

Whether the context implies continual increase.

Whether the context highlights gradual decline.

Whether the magnitude of change depends on current size.

These cues ensure accurate translation of the statement into mathematical form. Although the same symbolic structure appears, recognizing the correct sign of the proportionality constant is crucial for representing the intended behavior.

Interpreting the Meaning of the Exponential Differential Equation in Context

Once a differential equation of the form is written, students must understand what the expression communicates about the modeled phenomenon. This includes interpreting each component of the equation:

describes the instantaneous rate of change of the quantity.

represents the current state or amount.

encodes how strongly the rate responds to the current amount.

The model asserts that the system’s behavior is governed entirely by this dependence: the larger the quantity becomes, the faster it grows or decays (in magnitude). This relationship captures many natural and human processes in a concise mathematical expression.

Recognizing these features strengthens students’ ability to connect symbolic differential equations with real-world descriptions. The differential equation serves as a bridge between contextual language and the mathematical representation essential for further analysis.

FAQ

Look for phrases indicating that the rate of change depends directly on the current amount, even if the wording is subtle.

For example, statements such as “the quantity grows faster as it becomes larger” or “the decline slows as the amount decreases” often imply proportionality to the current value.

These descriptions highlight that the behaviour of the system is governed by the existing size of the quantity, which is the hallmark of exponential differential equations.

Yes. Percentage-based changes are inherently proportional, because a percentage is calculated from the current amount.

If a quantity increases by, for example, five per cent each hour, its rate of change is tied directly to its present size.

This allows the situation to be modelled using the same exponential differential equation structure.

Linear models assume the rate of change is constant, producing uniform increases or decreases.

Proportional models instead tie the rate to the current amount, so the quantity accelerates or decelerates over time.

Because the rate continually adjusts in response to the quantity itself, repeated compounding occurs, which is characteristic of exponential behaviour.

Only if the constant of proportionality changes sign during the process.

In traditional exponential models, the constant is fixed and therefore the behaviour remains consistently growth or decay.

However, if the context suggests that external factors may reverse the direction of change, the proportionality constant would need to be treated as time-dependent, which is beyond the simple exponential form used in this subsubtopic.

Avoid assuming that any mention of rapid increase implies exponential growth; the key feature is dependence on the current amount, not speed alone.

Also avoid interpreting “slowing down” or “speeding up” as necessarily non-exponential.

• A decrease can still be exponential if the rate is proportional to the current amount.

• Growth can be exponential even if it begins extremely slowly.

Focus on the structural relationship, not the magnitude of the changes described.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A population of insects is described verbally as follows:

“The rate of change of the insect population at time t is directly proportional to the size of the population.”

(a) Write a differential equation that models this situation.

(b) State whether the model represents exponential growth or exponential decay.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

(a) 2 marks

• 1 mark for correctly using derivative notation: dy/dt or an equivalent appropriate form.

• 1 mark for showing proportionality to the quantity: dy/dt = ky.

(b) 1 mark

• States that the model represents exponential growth because the rate is proportional to the population and no indication of decrease is given.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A chemical substance breaks down over time. A laboratory report states:

“The amount of substance decreases at a rate proportional to the amount present.”

(a) Identify the dependent and independent variables in this context.

(b) Write the differential equation that models the breakdown of the substance.

(c) The constant of proportionality is negative. Explain why this sign is appropriate for the situation.

(d) Describe in words how the amount of substance changes over time according to this model.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(a) 1 mark

• Dependent variable: amount of substance.

• Independent variable: time.

(b) 2 marks

• 1 mark for using correct derivative notation.

• 1 mark for writing the proportional relationship: dy/dt = ky.

(c) 1 mark

• Explains that the constant is negative because the amount is decreasing, so the rate of change must be negative for positive quantities.

(d) 1–2 marks

• 1 mark for stating that the amount decreases continuously over time.

• 1 additional mark for correctly stating that the rate of decrease becomes smaller in magnitude as the substance diminishes (i.e., the decrease slows down).