AP Syllabus focus:

‘Students interpret logistic differential equations and initial conditions to describe how the modeled quantity changes over time, without necessarily finding an explicit solution formula.’

Logistic differential equations describe growth that slows as a quantity approaches a limiting value. Interpreting their solutions focuses on understanding behavior over time without solving explicitly.

Understanding Logistic Differential Equations in Context

A logistic differential equation models situations where the rate of change depends both on the current amount and how close it is to a maximum sustainable level. When first introduced, the term carrying capacity requires a formal description.

Carrying Capacity: The maximum value a modeled quantity can approach given limiting factors in the environment or system.

A logistic equation typically appears in the form , though exact symbols may vary. For AP Calculus AB, the emphasis is not on solving this equation but on interpreting what the structure reveals about a system’s behavior. The equation expresses that growth is proportional to both current size and remaining capacity, illustrating why growth slows as nears the upper limit.

Independent of any explicit solution formula, the logistic structure communicates qualitative features: increasing behavior when the dependent variable is small, decreasing slopes as it nears its ceiling, and an eventual leveling off toward the carrying capacity.

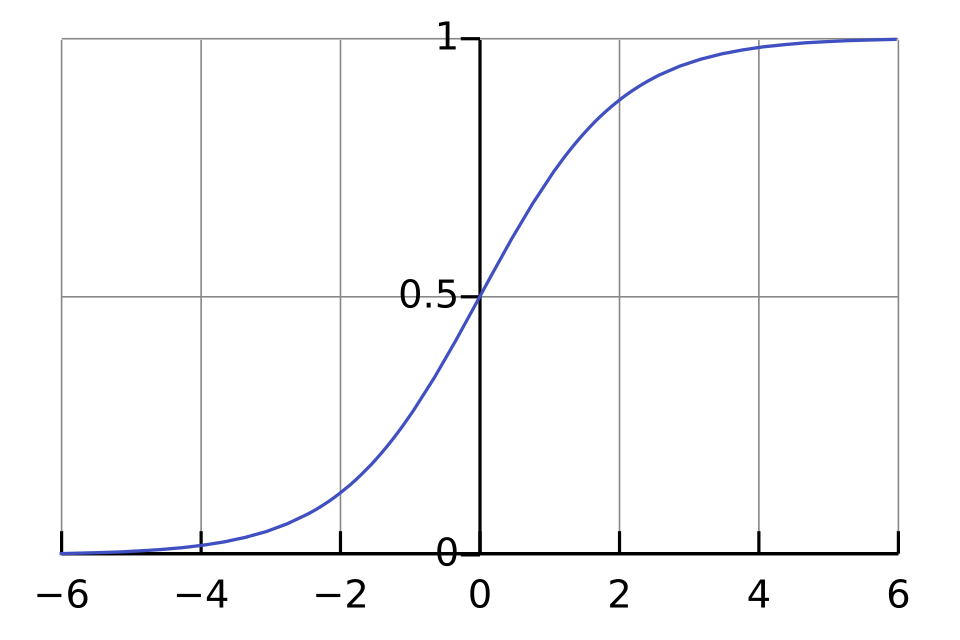

This S-shaped logistic curve illustrates slow initial growth, accelerated mid-range growth, and leveling off near a limiting value. It shows the qualitative behavior of logistic solutions without requiring an explicit formula. The normalized vertical scale adds generality beyond a specific applied context but remains consistent with the syllabus. Source.

Interpreting the Components of the Logistic Equation

The Role of Parameters and Structure

The parameter influences how quickly growth responds to current size, while sets the carrying capacity the quantity approaches over time. Logic about these parameters allows students to predict growth patterns without doing algebraic manipulation.

When interpreting logistic forms:

If is well below , then is large, so the rate of change is relatively high.

As increases, the difference shrinks, which reduces the rate of change.

When approaches , the rate of change becomes very small, suggesting flattening behavior.

These insights help describe the solution curve’s behavior qualitatively.

Using Initial Conditions to Understand Behavior

Why Initial Conditions Matter

A logistic model includes an initial condition, a given value of the dependent variable at a specific time, which determines which member of the logistic family is used. Although no explicit solving is required here, the initial condition tells us how the system begins and influences the entire trajectory of the solution curve.

Interpreting an initial condition requires understanding its conceptual role.

Initial Condition: A known value of the dependent variable at a specific value of the independent variable that identifies a particular solution from a family of possible solutions.

Between this definition and full interpretation lies the ability to reason qualitatively from context. Students use the logistic equation and initial value to describe how fast the quantity initially changes, whether it is growing or shrinking, and how it will behave in the long term.

Qualitative Features of Logistic Solutions

Rates of Change Without Explicit Solutions

A powerful aspect of logistic modeling is predicting how the solution behaves only by studying the differential equation and slope information.

Key qualitative observations include:

Growth is initially increasing when is small relative to the carrying capacity.

The rate of change reaches a peak when the modeled quantity is about halfway to the carrying capacity, because both growth factors are reasonably large.

The rate of change decreases after the midpoint, leading to slower growth as the quantity begins to saturate the environment or system.

Long-term behavior shows leveling off, approaching the carrying capacity asymptotically.

These statements allow complete descriptions of logistic behavior without computing explicitly.

Normal descriptive reasoning applies between equation and behavior, allowing students to link slope patterns with increasing, decreasing, or stabilizing trends.

Using Slope Behavior to Interpret Logistic Trajectories

What the Slope Indicates About Growth

The logistic differential equation gives immediate information about the slope , which describes the instantaneous rate of change. Although no equation box is required here, recognizing slope structure is essential.

Students interpret slope patterns by considering:

Sign of : Positive values indicate increasing behavior, which is typical for logistic models at all values below the carrying capacity.

Magnitude of : Larger magnitudes imply faster growth; logistic models show a rise and fall in slope magnitude as increases.

These slope ideas help students trace accurate qualitative behaviors, even when drawing or referencing slope fields.

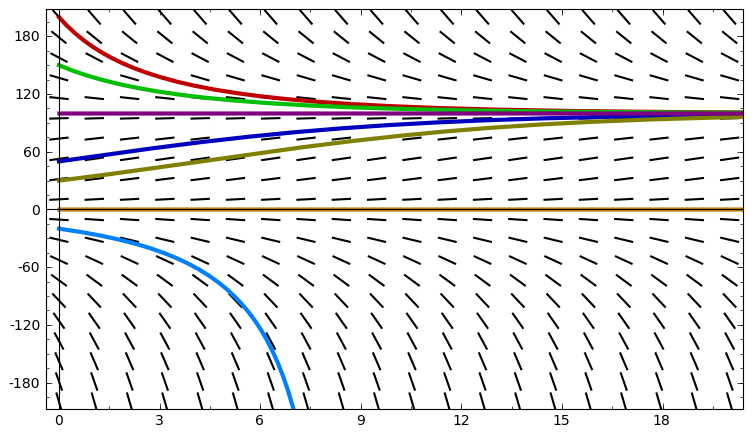

This slope field for a logistic differential equation shows how different initial conditions lead to solution curves that all approach the same carrying capacity. The heavy horizontal line represents the stable equilibrium, and the line segments show how local slopes guide each trajectory. The inclusion of negative -values and specific numerical scales extends beyond the AP syllabus but does not add conceptual difficulty. Source.

Connecting Logistic Differential Equations with Real-World Interpretation

Describing Situations Without Solving

Interpreting logistic solutions often involves explaining real-world implications. Students must articulate how the modeled quantity changes over time, including:

How initial population size affects early growth behavior.

Why growth slows as limiting factors become more significant.

What long-term behavior suggests about system stabilization or equilibrium.

In many contexts—population growth, spread of disease, resource-limited expansion—the logistic structure naturally captures diminishing growth due to constraints.

The emphasis in this subsubtopic is the ability to describe and reason qualitatively. Students interpret what the logistic equation and its initial condition communicate about the entire evolution of the modeled quantity without ever writing down an explicit solution formula.

FAQ

Logistic behaviour often appears in descriptions mentioning limited resources, slowing growth, or an upper limit that the quantity approaches over time.

Look for wording such as:

• growth that becomes harder as the population increases

• a maximum sustainable level

• diminishing rate of change despite continued growth

These linguistic cues suggest a logistic structure even when the mathematical form is not provided.

In a logistic model, the rate of increase falls to zero precisely as the quantity reaches the carrying capacity. The model assumes the system recognises limits continuously.

Because the rate cannot become positive beyond the capacity, the curve approaches the maximum without crossing, ensuring a smooth asymptotic approach rather than oscillation or overshoot.

A logistic equation can describe both increasing and decreasing trajectories depending on the initial condition.

• If the initial value is below the carrying capacity, the quantity increases.

• If the initial value is above the carrying capacity, the quantity decreases towards the capacity.

The model’s shape remains sigmoidal, but the direction of movement depends entirely on the starting point.

The midpoint, typically half the carrying capacity, is where the rate of change is highest. This marks the boundary between accelerating growth and decelerating growth.

Below the midpoint, both limiting factors work together to increase the rate of change. Above it, the diminishing availability of capacity outweighs the effect of size, producing a slowing rate.

Many real systems are too complex for clean algebraic solutions, yet their qualitative behaviour matters more than an explicit formula.

Interpreting without solving allows:

• rapid predictions about long-term trends

• understanding how initial conditions influence outcomes

• reasoning about constraints, saturation, and equilibrium

This makes the logistic framework valuable across biological, environmental, and social modelling scenarios.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A population P(t) grows according to a logistic differential equation. At time t = 0, the population is 10, and the carrying capacity is 80.

Without solving the differential equation, state whether the rate of change of the population is increasing or decreasing at t = 0, and explain why.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: States that the rate of change is increasing at t = 0.

• 1 mark: Explains that when the population is far below the carrying capacity, the expression (80 − P) is large.

• 1 mark: Concludes that the product P(80 − P) is relatively large at the start, giving a growing rate of change.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A quantity Q(t) satisfies the logistic differential equation dQ/dt = kQ(120 − Q), where k is a positive constant.

(a) Using only the structure of the differential equation, explain how the long-term behaviour of Q(t) can be determined without solving the equation.

(b) The initial condition is Q(0) = 20. Describe how this initial value affects the shape and early behaviour of the solution curve.

(c) Explain why the rate of change of Q(t) eventually decreases even though Q(t) is increasing.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(a)

• 1 mark: States that the long-term behaviour shows Q(t) approaching the carrying capacity 120.

• 1 mark: Explains that dQ/dt becomes small as Q approaches 120 because the factor (120 − Q) tends to zero.

(b)

• 1 mark: States that Q(0) = 20 determines which member of the logistic family is used.

• 1 mark: Explains that the solution begins with relatively slow growth when Q is small but not near zero.

(c)

• 1 mark: States that growth slows because (120 − Q) decreases as Q increases.

• 1 mark: Explains that the decreasing factor makes the product kQ(120 − Q) smaller, reducing the rate of change over time.