AP Syllabus focus:

‘Students study logistic growth models in which the rate of change of a quantity depends both on the current amount and on how close it is to a limiting carrying capacity.’

Logistic growth models describe situations where a quantity increases rapidly at first but slows down as it approaches a limiting value, reflecting realistic constraints on long-term growth.

Logistic Growth in Differential Equations

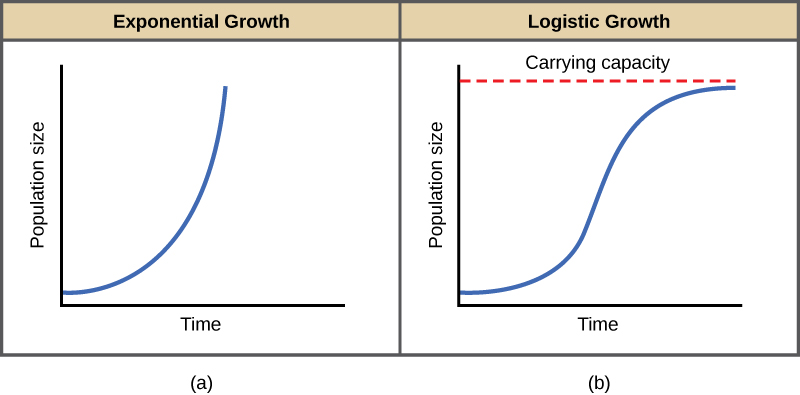

AP Calculus AB introduces logistic growth as a model for quantities whose rate of change depends on two simultaneous factors: how much of the quantity currently exists and how close it is to a limiting threshold. Logistic differential equations contrast with exponential equations, which assume unlimited resources and constant proportional growth. Logistic models incorporate restrictions found in real systems, such as limited space, energy, or resource-dependent processes, making them especially useful for describing biological, environmental, or resource-dependent processes.

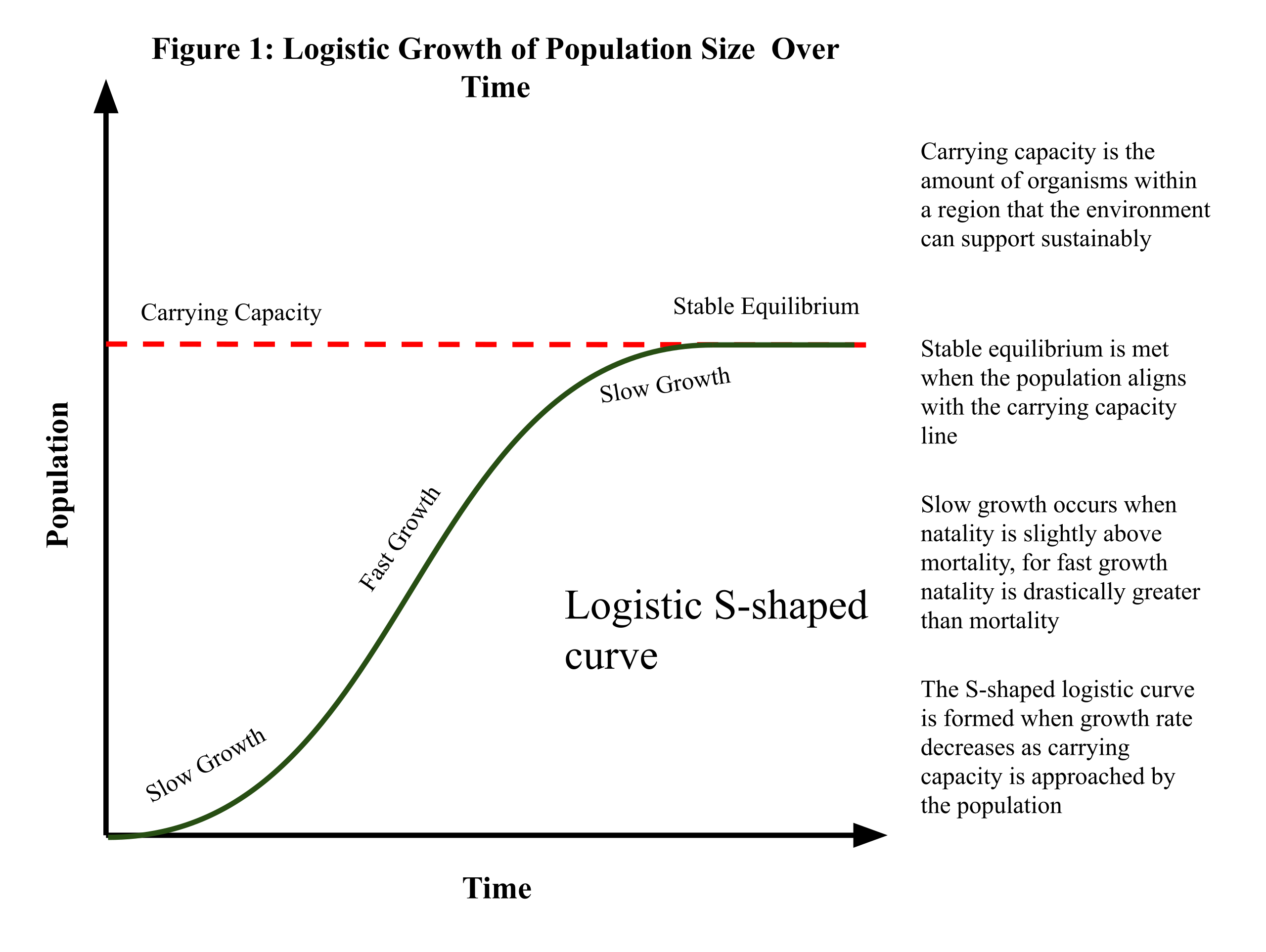

A logistic differential equation typically captures this idea through a structure where growth slows as the dependent variable approaches a maximum limit. This limit, called the carrying capacity, represents the largest value the quantity can sustain in the modeled system.

Understanding Carrying Capacity

The term carrying capacity refers to the maximum sustainable amount of a quantity in a given environment. It provides a natural upper bound on growth and is essential for interpreting logistic behavior.

Carrying capacity: The limiting value a growing quantity approaches in a logistic model, representing the maximum level supportable under given conditions.

As a population or quantity approaches the carrying capacity, the growth rate diminishes because fewer resources are available or constraints become more restrictive.

This S-shaped logistic curve shows growth that accelerates, slows, and levels off as it approaches the carrying capacity. The red dashed line marks the limiting value of the system. This diagram highlights how logistic models differ from exponential models by incorporating an upper bound. Source.

In logistic models, this diminishing growth is an inherent part of the differential equation, not an external adjustment.

The concept of carrying capacity contrasts with exponential growth, where no upper limit exists. Whenever a real-world process naturally slows due to competition, environmental limits, or saturation effects, logistic models serve as more realistic tools than exponential models.

Structure of a Logistic Differential Equation

While AP Calculus AB does not require memorizing or solving complex logistic equations, it does require recognizing their qualitative features. The logistic form expresses the rate of change as proportional both to the current amount and to the remaining “room” before reaching the carrying capacity.

= Dependent variable representing the quantity being modeled

= Independent variable, typically time

= Positive constant measuring growth responsiveness

= Carrying capacity, the limiting value approached as increases

This structure ensures that when the quantity is small, growth proceeds rapidly, and when it is close to the carrying capacity, growth slows significantly. The product form encodes both behaviors simultaneously.

The logistic model also implies that when or , growth stops, yielding equilibrium solutions. Although solving logistic equations is a BC-only topic, AP Calculus AB students interpret the relationship between the differential equation and the behavior of solutions.

Key Characteristics of Logistic Growth

Logistic growth curves exhibit distinctive and interpretable features based on the differential equation itself. Students should be able to describe these behaviors even without producing explicit solution formulas.

Early-Stage Behavior

At small values of the dependent variable, the expression is nearly equal to the carrying capacity, meaning the growth rate is dominated by the term . During this phase:

Growth resembles exponential behavior.

Resource limitations have minimal effect.

The slope of solution curves is positive and generally steep.

Mid-Stage Behavior

As the quantity increases toward half the carrying capacity, the factor begins to reduce overall growth:

Growth is still positive but slows progressively.

The interaction of current size and remaining capacity becomes more balanced.

The solution curve begins to bend, deviating from exponential growth.

Late-Stage Behavior

Near the carrying capacity, the term becomes very small:

Growth slows dramatically.

The curve levels off as it approaches the limiting value.

The carrying capacity acts as a horizontal asymptote for the solution.

These qualitative features allow students to infer long-term behavior directly from the logistic differential equation or from a slope field representing the equation.

Distinguishing Logistic Growth from Other Models

It is important for AP Calculus AB students to contrast logistic and exponential models since the syllabus emphasizes recognizing growth that slows as capacity limits are approached.

The left panel shows exponential growth, which increases without bound, while the right panel depicts logistic growth leveling off at its carrying capacity. The dashed line in the logistic graph highlights the limiting value that shapes long-term behavior. This comparison clarifies how logistic models incorporate realistic constraints absent in exponential models. Source.

Logistic growth is appropriate when:

A resource or environment limits continuation of exponential increase.

The growth rate depends simultaneously on the current level and remaining capacity.

The system stabilizes at a positive equilibrium rather than increasing without bound.

By reading the form of the logistic differential equation and interpreting its components, students can identify whether a scenario describes logistic growth and reason qualitatively about the behavior of its solution curves.

FAQ

The logistic equation incorporates both behaviours automatically through the interaction between the current population and the remaining capacity.

When the population is small, the remaining capacity is large, so growth occurs quickly.

As the population increases, the remaining capacity shrinks, reducing the rate of change until growth becomes negligible.

This dual behaviour follows from the structure of the logistic expression and does not require altering the values of the constants.

The equilibrium values occur where the rate of change is zero. One corresponds to a depleted population, and the other to the carrying capacity.

The lower equilibrium often represents extinction or zero initial presence, and it is typically unstable.

The upper equilibrium represents the maximum sustainable level of the quantity and is stable under logistic assumptions.

The steepness and timing of growth depend on the value of the proportionality constant.

A larger growth constant produces a steeper increase in the mid-growth phase.

A smaller constant results in slower adjustment toward the limiting value.

The carrying capacity controls the eventual level, but the growth constant influences how quickly it is approached.

Exponential growth assumes unlimited resources, whereas logistic growth embeds realistic constraints.

Real systems experience competition, resource scarcity, crowding effects, and environmental resistance.

These factors naturally reduce growth as a population expands, matching logistic assumptions.

Thus, logistic models reflect limits that arise in biological and ecological scenarios.

Slope fields illustrate the direction of growth visually without requiring algebraic manipulation.

Key features revealed by slope fields include:

• Steep positive slopes when the population is small

• Flattening slopes as values approach the carrying capacity

• Stabilisation near the upper equilibrium

This helps students reason qualitatively about logistic behaviour even without solving the differential equation.

Practice Questions

A population P is modelled by a logistic differential equation. Explain what happens to the rate of change of P as P approaches the carrying capacity.

1 mark: States that the rate of change decreases as the population approaches the carrying capacity.

1 mark: Explains that this is because the term representing remaining capacity becomes small or restrictive limits slow growth.

A population N grows according to the logistic differential equation dN/dt = kN(a − N), where k and a are positive constants.

(a) State the value of N for which the rate of change dN/dt is zero.

(b) Describe how the population changes when N is small compared with a.

(c) Explain why the population does not grow without bound, referring to the structure of the logistic equation.

(d) Sketch a possible graph of N against t, labelling the carrying capacity and the key features of logistic growth.

(a)

1 mark: Identifies N = 0 or N = a as values where the rate of change is zero.

(b)

1 mark: States that growth is approximately exponential or rapid when N is small.

1 mark: Explains that the factor (a − N) is close to a when N is small, giving large positive growth.

(c)

1 mark: Explains that as N approaches a, the factor (a − N) becomes small, reducing growth.

1 mark: States that this prevents the population from exceeding or growing beyond the carrying capacity.

(d)

1 mark: Sketch includes an S-shaped curve with slow initial growth, then rapid growth, then levelling off.

1 mark: Correctly labels the horizontal asymptote or upper limit as the carrying capacity.