AP Syllabus focus:

‘Regions are defined by one or more unifying characteristics or by patterns of activity that link places together.’

Regions help geographers interpret Earth’s complexity by grouping places that share meaningful characteristics or connections, allowing patterns, interactions, and spatial organization to be analyzed more effectively.

Understanding What Makes a Region

A region is a spatial unit distinguished by selected characteristics, processes, or connections that allow geographers to categorize space and analyze patterns more systematically. Because the Earth’s surface is diverse, grouping places into regions helps simplify complexity for clearer geographic interpretation.

Region: A spatial area defined by one or more unifying characteristics or by patterns of activity that create meaningful connections among places.

Regions vary widely in scale and purpose, ranging from small neighborhoods to entire continents. Geographers identify them to understand how and why places function together, what they share, and how their relationships shape larger spatial patterns. Regions can be based on natural or human-made properties, and the decision to recognize a region reflects analytical goals rather than strict, universally agreed boundaries.

Criteria for Defining a Region

Geographers define regions by selecting specific unifying characteristics or patterns of activity. These criteria depend on what spatial patterns need explanation or comparison.

Shared Physical or Human Characteristics

A region may form when multiple places exhibit consistent traits, either environmental or cultural. These shared features usually create a sense of similarity across the region.

Physical characteristics

Climate patterns, such as tropical rainforest distribution

Landforms, including mountain ranges or plains

Ecosystems, like tundra or desert biomes

Human characteristics

Language distributions

Political systems

Economic activity, such as manufacturing or agriculture

Cultural norms or historical experiences

Unifying Characteristic: A physical or human trait shared across multiple places that provides a basis for grouping them into a common region.

While these traits help delineate regions, geographers must decide which characteristics matter most for a given inquiry. Thus, regional definitions are analytical choices, not absolute classifications.

Functional Connections and Activity Patterns

Beyond shared traits, regions also emerge from patterns of activity that link places together. These connections emphasize movement, networks, and interactions.

Types of Functional Linkages

Geographers may identify a region based on connections such as:

Transportation corridors that move people and goods

Economic flows, including trade networks or labor markets

Communication systems linking urban centers

Service areas around a focal point, such as a metropolitan commuting zone

Functional Connection: A pattern of interaction—such as movement, economic exchange, or communication—that links multiple places into an interconnected spatial region.

Functional regions quantify how places work together through flows and interactions. Because such flows may shift over time, the boundaries and significance of these regions often evolve.

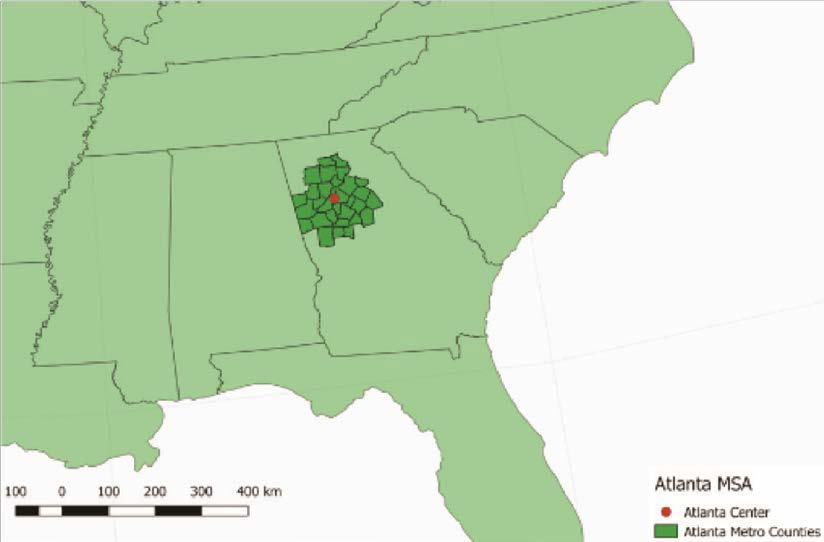

This map shows the Atlanta Metropolitan Statistical Area, a functional region defined by commuting patterns and economic linkages to a central urban core. Counties that are integrated with Atlanta through daily flows of people and jobs are grouped into a single region. Specific details of the MSA boundaries extend beyond the AP syllabus but clearly illustrate how functional regions operate in practice. Source.

Perception and Cultural Meaning

Regions do not always depend on observable traits or measurable interactions. Many regions exist because people perceive them as distinctive based on shared identity, cultural symbolism, or historical narratives.

Cultural and Perceptual Dimensions

People may define regions using meanings that arise from lived experiences or collective imagination. These regions reflect identity and belonging rather than strict physical or functional criteria.

Examples include:

“The Midwest” as understood by American residents

“The Middle East” shaped by cultural, historical, and political ideas

Neighborhoods identified by local reputation rather than precise boundaries

Perceptual Region: A spatial area defined by people’s shared feelings, attitudes, and cultural identities rather than by formal or functional criteria.

Such regions illustrate how human experience shapes geography, influencing how people navigate, describe, and understand the world.

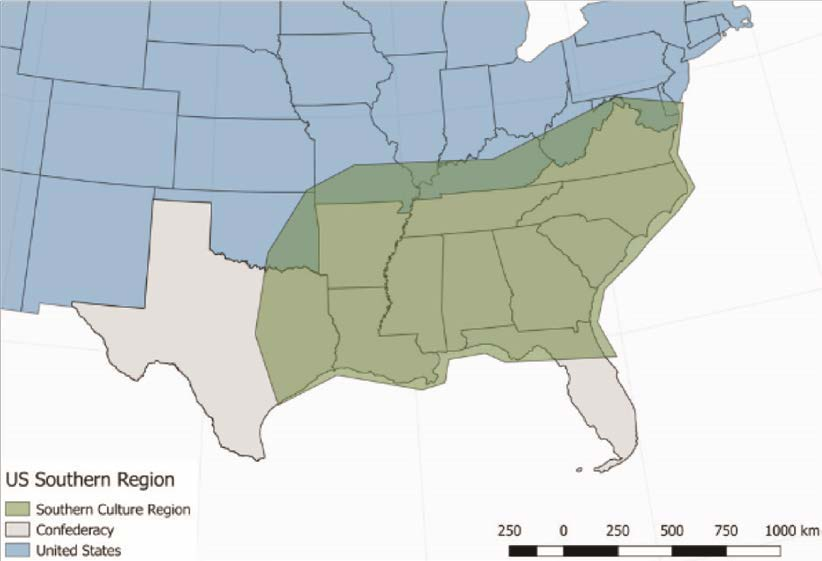

This map illustrates the American South as a perceptual region with fuzzy, overlapping boundaries rather than a single, universally accepted border. Different shades reflect varying interpretations of where “the South” begins and ends. Although the specific cultural and historical criteria exceed AP requirements, the image clearly demonstrates how perceptions define vernacular regions. Source.

Scale and Flexibility in Regional Definitions

Regions exist at multiple scales, and their characteristics may change depending on the scale of analysis. A region defined at a national scale may look very different when analyzed at a local scale, even if the same unifying characteristic is used.

Multiscalar Nature of Regions

Global scale: Broad climate zones or cultural realms

Regional scale: Economic trade blocs or political alliances

National scale: Administrative divisions or cultural regions within a country

Local scale: Neighborhoods, school districts, or municipal zones

Because regions are conceptual tools, geographers can redefine them to suit different analytical purposes.

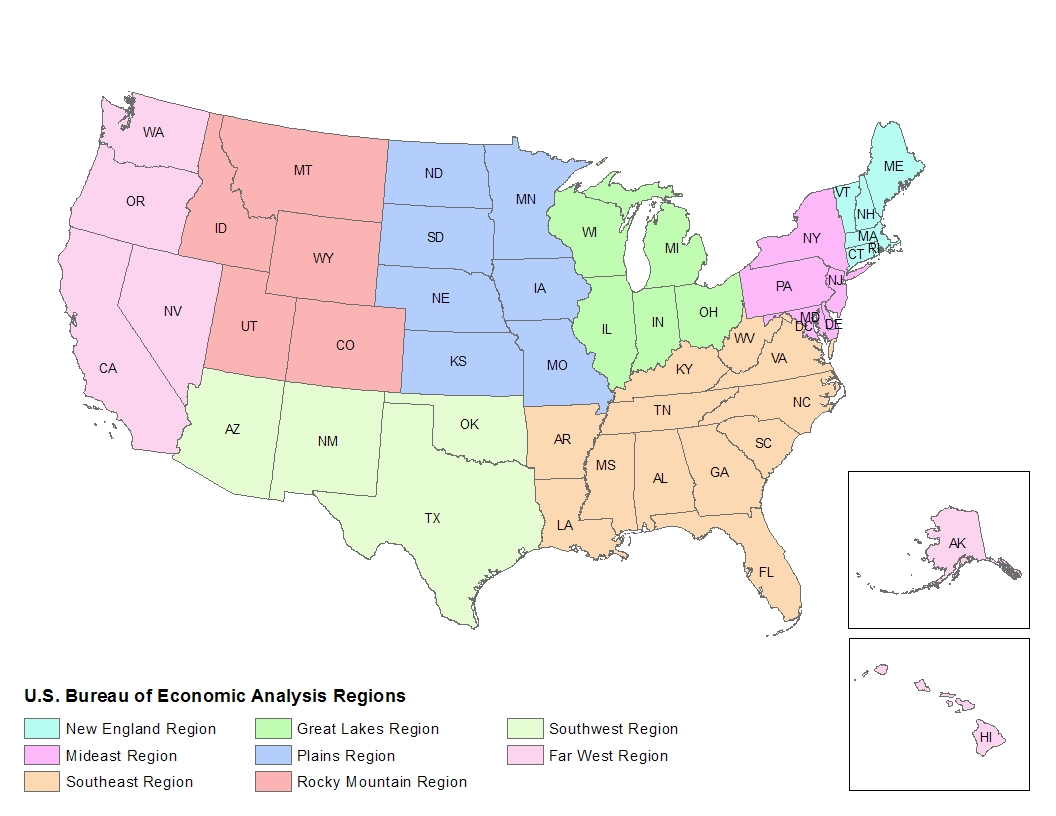

This map illustrates formal regions of the United States as defined by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. States are grouped according to measurable economic characteristics, demonstrating how geographers and institutions create regions for specific analytical purposes. The detailed BEA regional scheme extends beyond AP expectations but clearly reinforces the concept of formal regions defined by shared traits. Source.

A region created for climate research might differ significantly from one created to study migration or economic development.

Boundaries and Their Variability

Regional boundaries are rarely sharp or universally agreed upon. Instead, they often shift gradually, overlap with other regions, or appear contested.

Factors affecting boundary definition:

Changing demographics

New economic linkages

Evolving cultural identities

Environmental transitions, such as ecotones between biomes

Regions remain essential to geographic inquiry because they allow geographers to classify space in logical, purposeful ways. By identifying shared characteristics or functional connections, geographers can interpret patterns, compare places, and make sense of complex spatial relationships across the Earth’s surface.

FAQ

Geographers choose characteristics based on the research question or spatial pattern they want to analyse. The selection is purposeful, not random.

They typically prioritise traits that are:

Measurable or observable

Relevant to the geographic issue being studied

Consistent enough across space to justify grouping areas together

In many cases, the choice also depends on available data, meaning regions may be defined differently by different researchers.

Regions endure because they serve important cultural, political, or historical functions that reinforce their use, even if precision is lacking.

Shared identity, stories, or social meaning often sustain a region’s existence.

Over time, widespread usage by media, institutions, and residents helps normalise these regions, regardless of where their boundaries lie.

Digital mapping and geospatial tools allow geographers to detect patterns and flows that were previously invisible or hard to quantify.

Technology supports:

Real-time mapping of movement (e.g., phone-based mobility data)

More precise boundary adjustments using high-resolution satellite data

Identification of emerging functional regions through traffic, communication, or economic networks

As a result, regional definitions can now be more dynamic and data-driven.

Yes. Places frequently fall into several regional classifications depending on context, scale, or purpose.

For example, a city may simultaneously be part of:

A cultural region with shared traditions

An economic region defined by industry or commuting

A climate region determined by physical geography

Overlapping membership reflects the complexity of spatial relationships and the flexibility of regional frameworks.

Regional boundaries can influence how resources are allocated, how policies are designed, and how services are delivered.

Examples include:

Funding formulas tied to economic or demographic regions

Public transport planning based on functional metropolitan areas

Environmental management shaped by physical regions such as watersheds

Accurate regional definitions help ensure that decisions reflect actual patterns of activity and need.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Define the term region in geography and briefly explain one way in which regions help geographers interpret spatial patterns.

Question 1

1 mark for a correct definition of region (e.g., an area defined by one or more unifying characteristics or patterns of activity).

1 mark for explaining how regions simplify or organise spatial information.

1 mark for linking regions to the interpretation of patterns, relationships, or similarities across places.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using examples, explain how geographers use both unifying characteristics and functional connections to define regions. Discuss why the boundaries of such regions may vary depending on scale or perception.

Question 2

1 mark for explaining regions defined by unifying physical or human characteristics (e.g., climate, language, economic activity).

1 mark for providing an example of a formal region based on shared characteristics.

1 mark for explaining regions defined by functional connections (e.g., commuting flows, trade networks).

1 mark for providing an example of a functional region.

1 mark for explaining how boundaries can vary by scale (global, national, local) or over time.

1 mark for discussing perceptual or vernacular variation in regional boundaries due to cultural or subjective interpretations.