AP Syllabus focus:

‘Regional boundaries are often transitional, contested, and overlapping; geographers apply regional analysis at local, national, and global scales.’

Regional boundaries reflect complex social and environmental processes, often shifting across space and scale. Understanding overlapping, transitional, and contested boundaries helps geographers interpret spatial patterns and apply regional analysis effectively.

Understanding Regional Boundaries

Regional boundaries are not fixed lines; they frequently vary depending on the criteria used to define a region and the scale of analysis. A boundary that appears stable on a national map may look more fluid at a local scale. Because boundaries can be ambiguous, geographers examine how natural features, cultural traits, political decisions, and economic interactions contribute to their formation and transformation.

Transitional Boundaries

Transitional boundaries occur where characteristics change gradually rather than abruptly. A transitional zone is an area where the traits of two neighboring regions blend or shift across space.

Transitional Zone: A spatial area in which the defining characteristics of two adjacent regions mix gradually rather than change sharply.

A transitional zone might mark the shift from one climate type to another, or the blending of dialects across cultural regions.

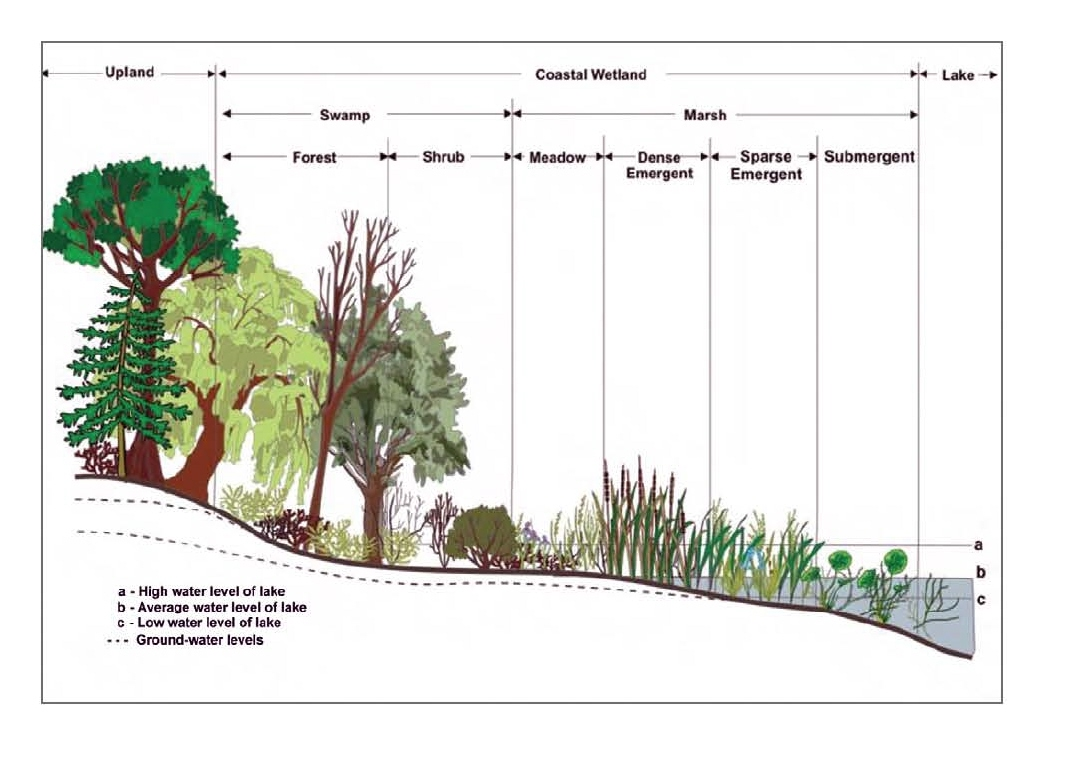

This cross-section illustrates the gradual ecological transition from upland forest to marsh, showing how characteristics change progressively across a transitional zone. It helps visualize how such boundaries blend rather than shift abruptly. Some ecological details, such as groundwater levels, exceed AP syllabus requirements but can be skimmed by students. Source.

In many cases, transitional boundaries emerge from long-term processes such as migration, environmental change, or shifts in economic activity. Recognizing these gradual changes helps geographers avoid oversimplified interpretations of regional identity.

Contested Boundaries

Contested boundaries are areas where different groups disagree on the region’s definition or extent. Contestation may arise from political conflicts, cultural claims, or competing economic interests. For example, debates over the limits of a metropolitan region often reflect differing policy goals, funding priorities, or identity narratives.

Contested Boundary: A boundary whose location or classification is disputed due to political, cultural, or economic disagreements.

Contested boundaries remind geographers that regions are socially constructed and often reflect power relations. Because boundaries can determine resource access, political representation, or cultural recognition, disputes over where a region begins or ends carry significant consequences.

Overlapping Boundaries

Overlapping boundaries occur when multiple regional classifications apply to the same area. Because regions can be based on different criteria—climate, language, land use, economic networks—one place may belong to several regions simultaneously.

Overlapping boundaries demonstrate that no single definition captures all aspects of a place. A city may lie within a specific agricultural region, a cultural region, and a political administrative region at once. This multiplicity underscores the need for geographers to choose regional frameworks that best match their analytical goals.

Applying Regional Analysis Across Scales

The specification emphasizes that geographers apply regional analysis at local, national, and global scales. Shifting scales can reveal patterns that are not visible at other levels of analysis.

Local Scale Analysis

At the local scale, regional analysis focuses on neighborhoods, communities, or small administrative units. This scale reveals micro-level variations in land use, social dynamics, and physical features. Local-scale boundaries often appear more detailed and nuanced, especially when examining transitional zones.

Bullet points that illustrate local-scale applications include:

Identifying zoning districts or economic subregions.

Mapping cultural identities such as ethnic enclaves.

Assessing environmental gradients within a metropolitan area.

National Scale Analysis

At the national scale, regions help organize broad patterns and support policy decisions. National governments often use formal regional divisions for planning, governance, and statistical reporting. Boundaries at this scale may appear more fixed, yet they still show transitional or contested characteristics when examined closely.

National-scale regional analysis supports:

Distribution of public services.

Identification of large-scale cultural or linguistic regions.

Planning for transportation and economic development.

Global Scale Analysis

At the global scale, regional analysis groups countries or continents based on shared attributes such as climate patterns, trade networks, or cultural heritage. These global regions are often more generalized, making overlapping and contested boundaries especially common.

This world map displays the United Nations’ formal geographical subregions, illustrating how global-scale regional analysis groups countries based on shared criteria. It highlights the broad, generalized nature of global regionalization. Some specific UN coding conventions exceed syllabus requirements but do not affect understanding. Source.

At the global scale, regional analysis groups countries or continents based on shared attributes such as climate patterns, trade networks, or cultural heritage. These global regions are often more generalized, making overlapping and contested boundaries especially common.

Global-scale applications include:

Comparing world regions in economic development studies.

Identifying global cultural realms.

Analyzing climate zones that span multiple continents.

Choosing Regional Criteria

Because boundaries depend on the characteristics used to define a region, geographers must carefully select criteria aligned with their research questions. The criteria affect:

How boundaries are drawn.

Which areas are included or excluded.

How regional relationships are interpreted.

Analytical choices shape both the clarity and the usefulness of regional definitions.

Interpreting Boundaries Through Geographic Thinking

The complexity of regional boundaries highlights the importance of spatial thinking. Geographers examine:

How interactions link places across invisible boundaries.

How identities shape perceptions of regions.

How political or economic forces alter boundary definitions over time.

By recognizing transitional, contested, and overlapping boundaries, geographers move beyond rigid classifications and develop richer interpretations of spatial patterns across all scales of analysis.

FAQ

Transitional boundaries often create hybrid cultural spaces where multiple identities coexist. Communities may adopt blended linguistic, religious, or social practices.

These areas can become zones of cultural exchange, where traditions interact more frequently than in core regions.

They may also experience fluid or shifting identities, especially where migration or economic change is ongoing.

Regional boundaries become contested due to shifts in political control, resource value, and demographic change.

Common causes include:

• Redistricting or changes in administrative power

• Competition for strategic territory or natural resources

• Divergent cultural or national identities

• Historical claims revived by political movements

Classifications differ because geographers prioritise different criteria depending on their analytical goals.

Some may emphasise cultural traits, while others focus on economic networks, environmental features, or political boundaries.

Scale further complicates classification, as a region may appear unified at the global scale but fragmented at the local scale.

Overlapping boundaries can make data categorisation inconsistent across sources.

For example:

• A city may fall into two economic regions but only one administrative region.

• Data gathered for one boundary framework may not align with data gathered for another.

This requires geographers to standardise or cross-reference datasets before analysis.

Residents may experience administrative uncertainty, such as which government authority provides services.

Contested boundaries can also affect:

• Access to schools, healthcare, or public resources

• Voting eligibility and political representation

• Cultural identity and community belonging

In some regions, disputes may lead to restricted movement, checkpoints, or security tensions.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain what is meant by a transitional boundary in regional geography.

Question 1

1 mark: States that a transitional boundary is an area between two regions.

2 marks: Identifies that characteristics change gradually rather than suddenly.

3 marks: Provides additional clarity, such as recognising blending of cultural, environmental, or economic traits across space.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using examples, analyse how contested and overlapping boundaries can influence the way geographers apply regional analysis at different scales.

Question 2

1–2 marks: Basic description of contested or overlapping boundaries.

3–4 marks: Explanation of how these boundaries influence regional analysis, such as affecting classification, data interpretation, or mapping decisions.

5–6 marks: Clear, well-developed analysis using appropriate examples (e.g., disputed political regions, cultural regions spanning multiple states) and linking these to differences at local, national, or global scales.