AP Syllabus focus:

‘As urban populations move within a city, economic and social challenges can emerge as neighborhoods gain or lose residents and investment.’

Urban residential mobility reshapes cities by redistributing populations, shifting investment patterns, and influencing social and economic conditions within neighborhoods as people move to, from, or within urban areas.

Residential Mobility and Urban Change

Residential mobility refers to the movement of people from one home to another within the same metropolitan area. This process is central to understanding urban change, because the relocation of households alters neighborhood demographics, housing demand, and patterns of investment. Mobility can be voluntary—often driven by housing preferences, life-cycle shifts, or employment changes—or involuntary, resulting from displacement, rising costs, or redevelopment pressures. Together, these dynamics influence which neighborhoods grow, which decline, and how urban areas transform over time.

Key Drivers of Residential Mobility

Several interconnected forces shape why and how residents move within a city. These drivers help explain spatial patterns of neighborhood change and the uneven distribution of opportunities across urban space.

Economic factors

Job relocation or new employment opportunities

Rising housing costs that prompt moves to more affordable areas

Shifts in local investment that alter housing supply and quality

Social and demographic factors

Family structure changes, such as marriage, divorce, or childrearing

Desire for proximity to cultural communities or social networks

School district preferences that motivate moves to specific zones

Environmental and infrastructural factors

Access to transportation, services, and amenities

Exposure to environmental hazards or disamenities

Neighborhood quality, safety, and overall livability

When these forces interact, they produce distinct patterns of residential turnover that directly shape neighborhood stability and transformation.

Mobility, Displacement, and Neighborhood Dynamics

Urban residential mobility can generate both opportunity and disruption. Neighborhoods experiencing high in-migration may see rising property values, new amenities, and improved services. Conversely, areas with persistent out-migration often struggle with declining tax bases, reduced investment, and deteriorating infrastructure.

As households move out of disinvested neighborhoods and into areas with better schools, services, or safety, some districts experience population loss and vacancy while others gain residents and new investment.

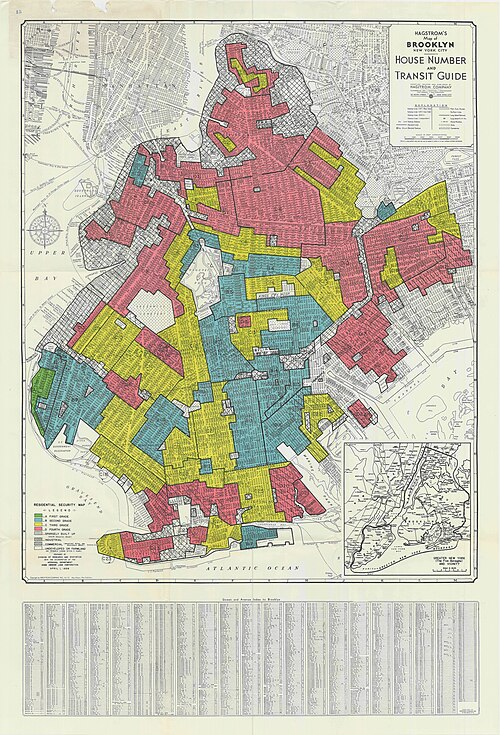

Brooklyn’s 1938 HOLC redlining map grades neighborhoods by perceived mortgage risk, directing investment toward some districts and away from others. These designations helped channel out-migration, disrepair, and segregation over time. The historical grading details exceed syllabus requirements but clearly illustrate institutional influences on residential mobility and neighborhood change. Source.

One significant form of residential mobility is displacement, the forced movement of residents due to unaffordable rent increases, redevelopment projects, or eviction threats. Displacement alters the social fabric of communities by reducing long-term residency and weakening informal support networks. It frequently affects lower-income households and marginalized populations disproportionately, contributing to uneven patterns of urban change.

Definitions Associated with Urban Change

Residential Mobility: The movement of individuals or households from one residence to another within the same metropolitan area.

Movement patterns reveal how different communities experience economic and social pressures differently across the urban landscape.

Displacement: The involuntary relocation of residents due to rising housing costs, redevelopment, or loss of affordable housing options.

Residents often weigh multiple factors before deciding to move, and these decisions contribute cumulatively to broader urban transformations.

Economic and Social Consequences of Mobility

Residential mobility shapes both the economic conditions and social character of neighborhoods. Because households bring labor, purchasing power, and social capital, their movements generate ripple effects that influence urban development patterns.

Economic consequences

Investment and disinvestment cycles

Inflow of higher-income residents can stimulate new businesses, infrastructure upgrades, and property redevelopment.

Outflow of residents can reduce retail activity, discourage business presence, and lead to property decline.

Housing market shifts

Increased demand raises rents and home prices.

Decreased demand may create vacancies, reducing local revenue and weakening housing quality.

Social consequences

Changing demographic composition

Ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic shifts reshape neighborhood identities.

Arrival or departure of cultural communities influences local institutions and public spaces.

Community cohesion and social networks

High mobility can erode trust, weaken ties, and destabilize community organizations.

Stable residency supports local participation, informal governance, and neighborhood resilience.

These impacts reveal how mobility produces uneven outcomes, benefitting some areas while challenging others.

Mobility and Urban Inequality

Residential mobility plays a major role in reinforcing or reducing urban inequality. Neighborhoods gaining residents—particularly affluent newcomers—tend to accumulate investment, political influence, and improved services. In contrast, neighborhoods losing residents frequently face limited economic opportunities, reduced public services, and concentrated disadvantage.

Gentrification occurs when reinvestment and higher-income in-migrants transform previously disinvested neighborhoods, raising property values and rents and often displacing lower-income long-term residents.

New townhouses and older homes stand side by side on Willow Street in East Austin, illustrating reinvestment and demographic change. These visible contrasts signal shifting land values and displacement pressures. The architectural specifics exceed syllabus scope but provide a clear real-world example of neighborhood transformation through residential mobility. Source.

Uneven access to services arises when moving residents cluster in areas with high-quality schools, transit, or healthcare facilities, leaving other areas under-resourced.

Spatial segregation intensifies when mobility patterns reflect racial or socioeconomic divisions.

Housing affordability pressures increase when rising demand in some districts displaces long-term residents.

Understanding these inequalities is essential for analyzing how mobility contributes to broader patterns of urban restructuring.

Urban Policy Influences on Mobility

Local governments shape residential mobility through zoning, housing programs, and development incentives. Policies can either stabilize communities or accelerate neighborhood turnover.

Affordable housing initiatives aim to reduce forced mobility by expanding access to stable, reasonably priced homes.

Redevelopment and infrastructure projects may revitalize neighborhoods but also risk displacing residents.

Tenant protections and rent regulations can limit involuntary moves and preserve community stability.

These policies demonstrate that urban change is not purely organic; it is structured by decisions about land use, investment, and resource allocation.

Residential Mobility as a Lens for Understanding Urban Change

Urban geographers map residential mobility and neighborhood change across an entire metropolitan area to see which districts are gentrifying, which are stable or declining, and how these patterns differ by race and income.

FAQ

Residential mobility involves movement within the same urban area, while broader migration refers to movement between regions or countries.

Because these moves occur locally, residential mobility reshapes neighbourhood‐level dynamics more quickly, influencing small‐scale changes in housing demand, school enrolment, and local services.

Local governments typically respond to residential mobility faster than to large migration trends, making it a key driver of immediate neighbourhood change.

Frequent movers often include:

Young adults and students seeking flexible, affordable housing

Renters with unstable leases

Low‐income households affected by rising costs

Families adjusting to school catchment areas

These groups tend to respond quickly to shifts in affordability, life‐cycle changes, or service availability, making them sensitive indicators of urban change.

High mobility can disrupt school stability, as fluctuating enrolments make it harder to plan staffing and resources.

Neighbourhoods gaining residents often experience overcrowding, prompting new school construction or boundary changes.

Areas losing households may face declining enrolment, school closures, or programme cuts, which can further accelerate out‐migration.

Stable neighbourhoods often benefit from:

Strong social networks and local identity

Long‐term homeownership

Consistent investment in public services

Effective local planning and zoning controls

Even when surrounding districts experience rapid change, these factors help maintain cohesion and reduce turnover.

Landlords influence mobility through rent setting, lease conditions, and maintenance decisions. Poor upkeep or rapid rent rises can push tenants to relocate.

Developers shape mobility by introducing new housing types or redeveloping older properties, which can attract higher‐income residents and alter neighbourhood composition.

These market actors play a significant role in determining who stays, who moves, and how neighbourhoods evolve.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way residential mobility can lead to neighbourhood decline within a city.

Mark scheme

1 mark for identifying a relevant process (e.g., out-migration, disinvestment, population loss).

1 mark for explaining how this process contributes to neighbourhood decline (e.g., reduced tax revenue, fewer services).

1 mark for linking the explanation to an outcome (e.g., deteriorating infrastructure, increased vacancy).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using an urban example of your choice, analyse how both voluntary and involuntary residential mobility shape patterns of social and economic change in a city.

Mark scheme

1 mark for correctly defining or describing voluntary mobility (e.g., moves due to preference, jobs, schools).

1 mark for correctly defining or describing involuntary mobility (e.g., displacement due to rising rents or redevelopment).

1–2 marks for explaining how voluntary mobility influences social or economic patterns (e.g., middle-income in-migration increasing investment).

1–2 marks for explaining how involuntary mobility influences social or economic patterns (e.g., loss of long-term residents reducing community cohesion).

1 mark for using a clear and appropriate urban example to support the argument.