AP Syllabus focus:

‘Housing challenges include discrimination and unequal access to housing, including redlining, blockbusting, and affordability pressures.’

Urban housing inequality reflects historical and contemporary forces that restrict access to secure, affordable housing while shaping uneven neighborhood development and long-term social outcomes.

Housing Discrimination and Affordability

Housing discrimination and affordability pressures are central challenges in urban change because they directly influence who can live where, under what conditions, and at what cost. The geography of housing is shaped by both market forces and institutional decisions, creating spatial patterns of opportunity and disadvantage. In AP Human Geography, this subsubtopic highlights how discriminatory practices, economic inequalities, and policy choices interact to produce uneven outcomes across urban areas.

Key Forms of Housing Discrimination

Housing discrimination restricts equal access to neighborhoods, mortgages, rental markets, and homeownership opportunities. These practices can be intentional or structural but consistently limit the mobility and well-being of certain groups.

Redlining was the systematic denial of mortgages or investment based on a neighborhood’s racial or ethnic composition.

Redlining: A discriminatory practice in which banks and federal agencies refused loans or insurance to neighborhoods deemed “risky” based largely on racial criteria rather than financial data.

Redlining created long-lasting spatial inequalities by promoting disinvestment, lowering property values, and restricting generational wealth accumulation.

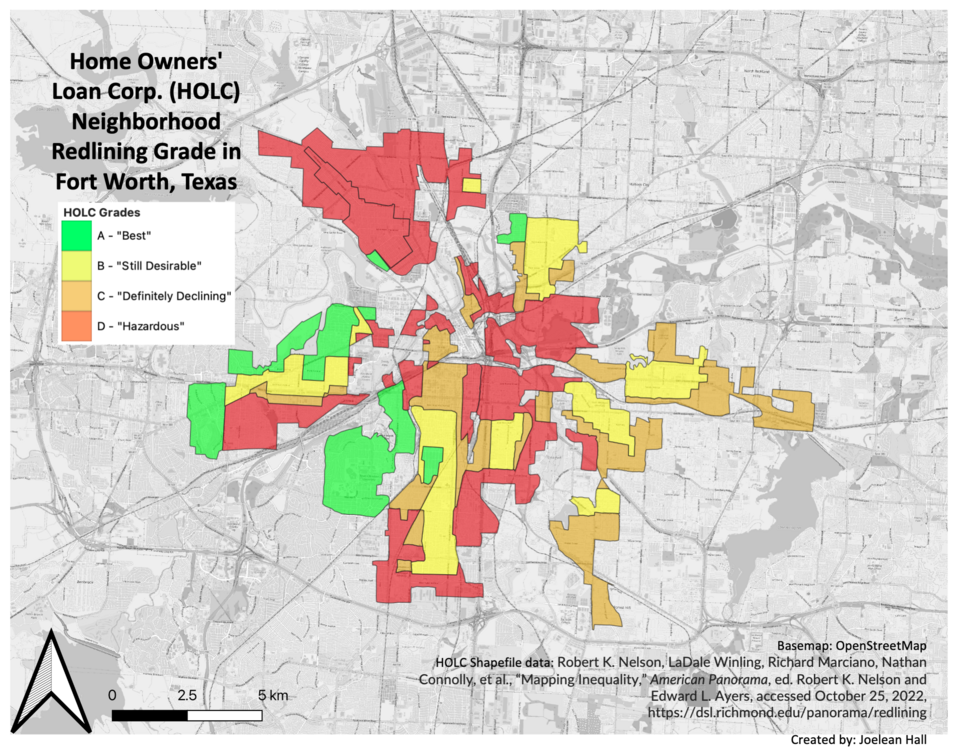

Map of Fort Worth showing federally assigned HOLC neighborhood security grades. The red and yellow zones illustrate how minority and low-income neighborhoods were labeled risky, discouraging investment. The map includes detailed street-level information beyond the syllabus, but it directly illustrates the spatial logic and legacy of redlining. Source.

Blockbusting involved real estate agents manipulating racial anxieties to profit from neighborhood turnover.

Blockbusting: A practice in which real estate agents encouraged White homeowners to sell homes quickly and cheaply by suggesting that racial minorities were moving in and property values would fall.

Blockbusting accelerated racial segregation and shifted demographic composition rapidly, contributing to urban decline in many U.S. cities while reinforcing restrictive housing markets.

Mechanisms That Reinforce Unequal Access

Housing discrimination involves more than explicit historical practices. Contemporary processes continue to influence the availability and affordability of housing.

Steering, the practice of realtors guiding clients toward or away from neighborhoods based on race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status, shapes residential patterns and limits choice.

Predatory lending, which includes high-interest loans or exploitative mortgage terms, disproportionately impacts marginalized groups, increasing foreclosures and housing instability.

Zoning regulations, particularly exclusionary zoning, can limit affordable housing construction by requiring large lot sizes or banning multi-unit buildings, thereby reinforcing socioeconomic separation.

These mechanisms create cumulative effects in the urban landscape, often aligning with broader forms of environmental injustice, disamenity zones, and uneven access to services across metropolitan regions.

Housing Affordability Pressures

Affordability concerns arise when housing costs rise faster than incomes, reducing residents’ ability to secure adequate shelter.

Rising land values near job centers, transit hubs, or revitalizing neighborhoods increase rents and home prices.

Stagnant wages or limited access to well-paying jobs make it harder for households to compete in tight housing markets.

Shortage of affordable units results from limited construction, restrictive zoning, and competition from higher-income residents.

In rapidly growing cities, affordability challenges can push residents farther from employment centers, increasing commuting distances and reinforcing spatial inequality.

Urban Spatial Patterns Resulting from Discrimination and Affordability Issues

Housing challenges generate distinct spatial outcomes that are visible in many urban regions.

Segregation patterns emerge as demographic groups become concentrated in specific neighborhoods due to historic discrimination and contemporary affordability pressures.

Gentrification patterns occur when rising investment and property values displace existing residents. While not inherently discriminatory, gentrification often intersects with affordability problems and reveals gaps in tenant protections.

Suburbanization of poverty reflects affordability shifts as low-income households move to outer suburbs lacking adequate services, transportation, or employment proximity.

Spatial mismatch, when low-income residents live far from job opportunities, results from exclusionary housing practices and affordability constraints.

These patterns reflect the geography of access: urban residents with more resources can choose from a wider range of neighborhoods, while marginalized groups face constrained options tied to broader economic structures.

Government Policies, Market Forces, and the Role of Planning

Government actions and institutional decisions can either reinforce or mitigate housing discrimination and affordability issues.

Fair housing laws seek to prohibit discrimination in renting, selling, and financing, although enforcement remains uneven.

Affordable housing programs, including housing vouchers, public housing, and inclusionary zoning, aim to expand access for low-income residents.

Rent control and stabilization attempt to limit rapid rent increases, though these policies vary widely in approach and effectiveness.

Urban renewal policies, historically, displaced communities of color through highway construction and redevelopment projects, demonstrating the intersection of planning and inequality.

Urban planners increasingly analyze land-value gradients, commuting patterns, and residential density to design housing policies that reduce spatial inequality and support more inclusive metropolitan regions.

Social and Demographic Effects

Housing discrimination and affordability pressure shape demographic change, community stability, and long-term opportunities.

Schools, food accessibility, health care, and public services vary greatly by neighborhood, influencing life outcomes.

Limited access to homeownership reduces wealth generation across generations.

Spatial concentration of poverty can intensify crime, environmental burdens, and disinvestment.

Housing instability contributes to frequent moves, evictions, and challenges in maintaining employment and education.

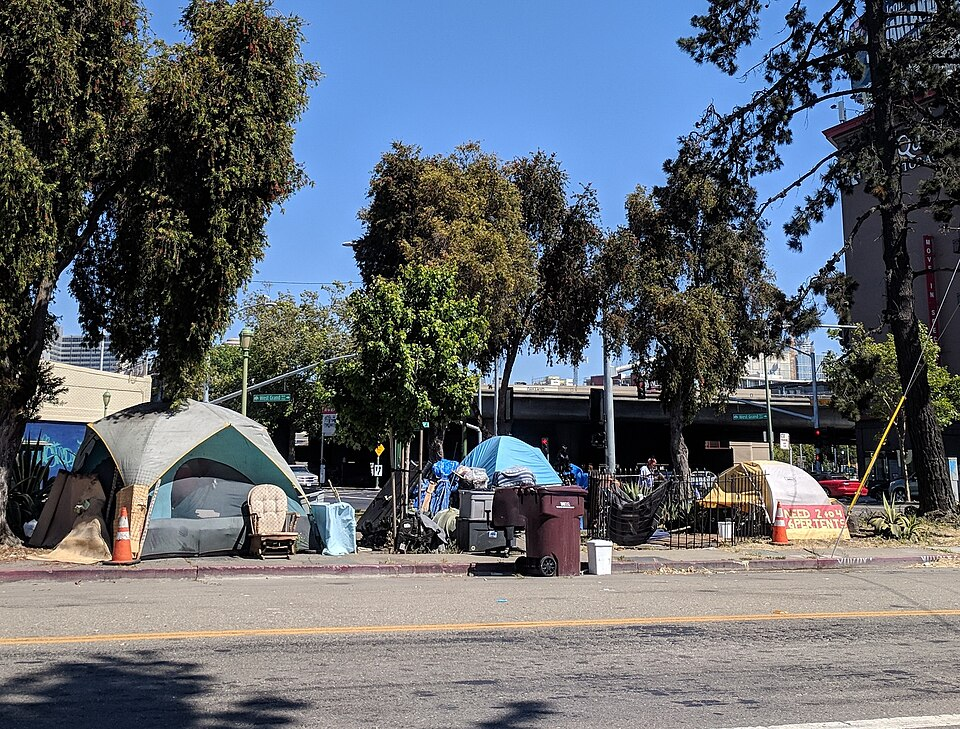

Homeless encampment beside a freeway interchange in Oakland, illustrating severe housing insecurity. Tents and shelters cluster near traffic lanes, showing how affordability pressures push residents into marginal urban spaces. The presence of overpasses and vehicles provides real-world context beyond the syllabus while reinforcing the geographic impacts of housing instability. Source.

FAQ

Following the end of formal redlining, lenders increasingly used credit scores, employment histories, and neighbourhood investment trends to guide decisions.

These criteria often mirrored earlier racialised patterns because decades of disinvestment had already lowered property values and household wealth in formerly redlined areas.

As a result, residents in these neighbourhoods continued to face higher borrowing costs or reduced access to mortgages, perpetuating uneven housing opportunities.

Private investors often purchase lower-cost properties in central or transitional areas, expecting rising values.

This can trigger displacement pressures through:

Larger-scale redevelopment

Conversions of rental units into higher-priced accommodation

Increased competition for remaining affordable units

Such dynamics raise market rents and reduce long-term housing security for lower-income residents.

Improved transport links can increase demand for nearby housing, raising land values as accessibility improves.

However, areas far from reliable transport are often more affordable but come with higher travel costs and reduced employment access.

This trade-off reinforces spatial inequalities when households must choose between affordable housing and convenient commuting.

New housing developments may target higher-income residents, offering premium units that do not ease pressure on affordable housing stock.

Additionally, rising demand due to population growth can outpace construction rates.

Speculation by investors can further inflate prices, limiting affordability even when supply expands.

Local authorities rely heavily on property tax revenue to fund services, creating incentives to favour higher-value development.

Rising property taxes can increase housing costs for both owners and renters, especially in areas undergoing reinvestment.

In some cities, tax relief programmes or caps are used to reduce displacement, but their effectiveness varies widely.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Define housing discrimination and identify one historical practice that contributed to unequal access to housing in urban areas.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark for a correct definition of housing discrimination (e.g., unequal treatment or restricted access to housing based on characteristics such as race, ethnicity, or income).

1 mark for naming a historical discriminatory practice (e.g., redlining, blockbusting, steering).

1 mark for briefly describing how the identified practice worked (e.g., redlining involved denying mortgages to neighbourhoods based on racial composition).

(4–6 marks)

Explain how both government policy and market forces contribute to contemporary housing affordability challenges. Use specific geographic processes or examples to support your answer.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

1–2 marks for explaining the role of government policy (e.g., exclusionary zoning limiting affordable housing construction; insufficient regulation of mortgage lending; uneven enforcement of fair housing laws).

1–2 marks for explaining market forces (e.g., rising land values in central areas; wage stagnation; supply shortages driving up rents).

1–2 marks for using specific geographic processes or examples (e.g., suburbanisation of poverty, displacement in gentrifying districts, spatial mismatch between housing and employment).