AP Syllabus focus:

‘Rising crime and fear of crime can reshape daily movement, investment decisions, and perceptions of safety within cities.’

Urban crime and related social challenges significantly influence how cities function by shaping resident behavior, economic decisions, mobility patterns, and the overall perception of safety within urban spaces.

Understanding Crime as an Urban Process

Crime in cities reflects broader social, economic, and spatial processes. Urbanization concentrates diverse populations, creates varied land uses, and can heighten inequalities, all of which influence why and where crime occurs. Rising crime does not act alone; its social consequences, particularly fear of crime, may alter how individuals use the city and how institutions invest in urban neighborhoods.

Crime Types and Spatial Patterns

Urban crime can include property crime, violent crime, and public disorder, each showing distinctive geographic patterns. Areas with dense commercial activity may experience higher property crime, while marginalized neighborhoods can face disproportionate levels of violent crime due to long-term disinvestment and limited institutional support.

Urban Crime: Harmful or unlawful behavior occurring within an urban area, shaped by demographic, economic, and spatial characteristics.

Crime patterns often cluster and diffuse in identifiable ways. For instance, hot spot clusters emerge where land use, transportation networks, and social conditions overlap to produce concentrated crime activity. Crime tends to follow predictable rhythms influenced by daily commuting flows and the presence or absence of public space supervision.

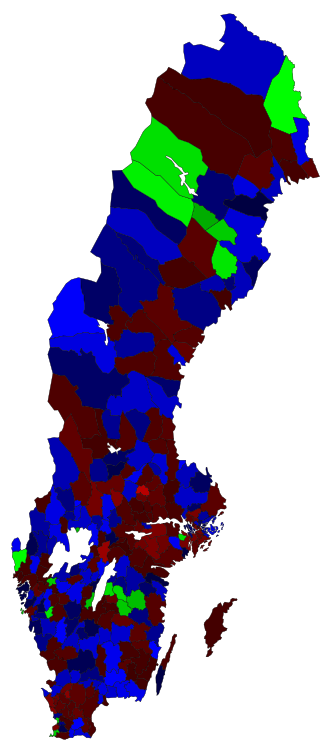

In many cities, violent and property crime are not evenly distributed but cluster in particular neighborhoods and corridors.

This map shows relative rates of violent crime per capita across Swedish municipalities, with brighter reds indicating higher levels of reported violence. It illustrates how crime clusters geographically, shaping perceptions of safety and influencing urban social challenges. Although specific to Sweden, the spatial patterns help visualize uneven crime distribution relevant to many cities. Source.

Fear of Crime and Its Geographic Impacts

Fear of crime—whether based on real experiences or perceived risk—can independently reshape how people navigate a city. The social and psychological impacts may be as influential as crime itself.

How Fear of Crime Reshapes Daily Life

Residents may avoid certain neighborhoods or alter travel times, reducing access to employment, education, and services. These behavioral shifts have spatial consequences:

Reduced foot traffic in areas perceived as unsafe

Increased reliance on private vehicles over public transit

Avoidance of parks, transit stops, or commercial corridors

Declining evening or nighttime activity in central districts

These reactions can reduce community cohesion by discouraging informal social interaction in public spaces. As fewer people use shared spaces, actual and perceived safety can deteriorate further.

Investment Decisions and Urban Development Patterns

Crime and its associated fears strongly influence urban investment and land-use choices. Investors, developers, and businesses often respond to crime trends by reallocating resources away from high-risk areas, while local governments adjust planning and policing strategies.

Disinvestment and Reinforcement of Inequality

Neighborhoods labeled unsafe may face long-term disinvestment, which occurs when economic actors withdraw financial support from an area. Reduced investment contributes to:

Lower property values

Business closures or relocation

Deterioration of infrastructure and housing

Decreased municipal revenue for public services

These shifts create cyclical patterns in which disinvestment intensifies existing socioeconomic challenges. In some cases, entire districts become zones of decline, where limited economic activity further discourages reinvestment.

A normal sentence appears here to maintain the required separation before adding another definition.

Disinvestment: The process through which financial support, business activity, or public resources are withdrawn from a neighborhood, often leading to decline.

Perceptions of Safety and Urban Identity

Perception often outweighs statistical reality in shaping how residents and outsiders understand a neighborhood. A single high-profile crime incident can redefine an area’s reputation, influencing migration, tourism, and commercial decisions.

Spatial Stigmatization

Neighborhoods associated with crime may face spatial stigmatization, a form of negative labeling in which places are perceived as unsafe or undesirable. This process can alter:

Real estate demand

School enrollment patterns

Business location choices

Social interactions between neighborhoods

Spatial stigmatization can produce self-reinforcing patterns, where negative perceptions reduce opportunities, which in turn sustain or worsen crime conditions.

Crime Prevention and Urban Design Responses

Cities often respond to crime with planning, policing, and architectural interventions aimed at reducing risk and improving perceptions of safety.

Urban Design Strategies

Many strategies stem from the principle that built environments influence social behavior. Approaches include:

Improved lighting to increase visibility in public spaces

Active street fronts, where windows, shops, and residences overlook sidewalks

Pedestrian-friendly design that encourages natural surveillance

Maintenance and beautification, which signal care and reduce disorder

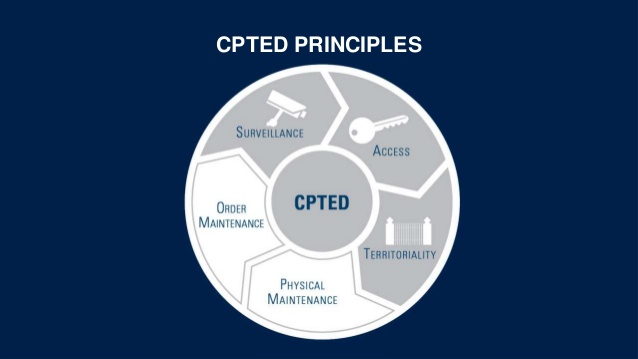

These strategies align with Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED), which argues that thoughtful urban design can reduce opportunities for crime.

Cities respond with formal social control measures such as increased policing, CCTV, and security infrastructure, which can reassure some residents while making others feel watched or targeted.

This photograph shows multiple CCTV cameras monitoring different directions from a building corner, representing formal surveillance in urban public space. Such technologies are often introduced in response to crime or fear of crime. While not depicting crime, the image illustrates how security infrastructure becomes embedded in the city. Source.

A bridging sentence ensures spacing before introducing the next definition.

Natural Surveillance: The ability for people to observe public spaces, thereby increasing perceived and actual safety by deterring crime.

Social Programs and Community-Based Approaches

Beyond physical design and policing, many cities adopt social strategies to address the root causes of crime. These approaches aim to strengthen community ties, expand youth opportunities, and increase trust between residents and public institutions.

Community-Level Interventions

Common initiatives include:

Youth education and job-placement programs

Community policing focused on cooperation and trust-building

Public space activation, such as markets or events

Social services that address housing, mental health, and substance use

Urban design and planning can mitigate crime and fear by creating eyes on the street, improving lighting, encouraging mixed land use, and designing active public spaces.

This diagram highlights core CPTED principles—surveillance, access, territoriality, and maintenance—showing how environmental design can reduce crime opportunities. It visually reinforces how built environments shape safety and public behavior. The image includes some additional labeled elements, but all support the central concept that design influences urban crime patterns. Source.

FAQ

Land use shapes crime opportunities by bringing together different activities, densities, and groups of people. Commercial areas often experience theft due to high footfall and valuable goods, while nightlife districts may see more disorder after dark.

Residential areas vary depending on housing type, socioeconomic status, and levels of community surveillance. Large transport hubs can also become crime hot spots because of anonymity and constant movement.

Reputations often lag behind reality because perceptions are shaped by long-standing narratives, media portrayals, or historic events.

Once an area becomes stigmatised, residents and outsiders may continue to avoid it, limiting new investment and slowing positive change. This creates a feedback loop where improved conditions take time to translate into improved image.

Strong social ties can reduce crime by increasing informal social control, where residents watch over shared spaces and challenge antisocial behaviour.

Community cohesion also supports collective action, enabling neighbourhoods to advocate for services, organise events, and maintain public spaces. These activities strengthen territoriality and signal stability to both residents and visitors.

Transport nodes can become crime hot spots due to crowds, anonymity, and limited supervision. Good design reduces this risk by improving lighting, ensuring sightlines, and positioning help points or staff.

Safety perception also rises when stations have active frontages, visible maintenance, and reliable services, encouraging greater legitimate use and reducing opportunities for offending.

Fear of crime can discourage customers from visiting certain areas, reducing sales for shops, restaurants, and night-time venues.

It may also deter workers from commuting to particular locations, limiting labour supply. Event organisers may avoid hosting festivals or markets in areas perceived as unsafe, reducing cultural and economic vibrancy.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain how fear of crime can influence daily movement patterns within a city.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying that fear of crime alters how people move through urban spaces (e.g., avoiding certain areas).

1 mark for describing a specific behavioural change (e.g., avoiding walking at night, choosing different routes).

1 mark for linking this to broader spatial effects (e.g., reduced foot traffic contributing to declining public space use).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Discuss how rising crime and associated social challenges can influence urban investment and neighbourhood change. Use examples to support your answer.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying that rising crime can discourage investment.

1 mark for explaining how perceptions of safety shape investor or business decisions.

1 mark for describing the process of disinvestment or the emergence of zones of decline.

1 mark for linking crime-related stigma to reduced property values or population loss.

1 mark for explaining how these changes reinforce socioeconomic inequalities.

1 mark for a well-developed example illustrating any of these processes.