AP Syllabus focus:

‘Urban challenges can include unequal access to services such as schools, health care, food, parks, and reliable transportation.’

Access to essential urban services strongly shapes residents’ opportunities, influencing social mobility, economic participation, and quality of life while revealing disparities linked to infrastructure, policy decisions, and neighborhood conditions.

Unequal Access as a Core Urban Challenge

Unequal access to services and opportunities arises when residents face barriers to obtaining schools, health care, food options, parks, and reliable transportation. These services are foundational to social well-being, yet their distribution often reflects broader patterns of urban inequality, including historical segregation, market forces, and uneven public investment. Urban geographers analyze how these disparities evolve and how they shape spatial patterns of advantage and disadvantage across metropolitan areas.

Understanding Access and Opportunity

Access refers to the ability of individuals or groups to reach and utilize essential services within the urban environment. Opportunity reflects the broader range of social and economic benefits made possible by accessing these services. When either is restricted, neighborhoods can experience cumulative disadvantages, such as weaker educational outcomes or higher health vulnerabilities.

Access: The ability of individuals to reach and use essential goods, services, and opportunities within the urban environment.

Variation in access often reflects the spatial mismatch between where people live and where services are located. Suburbanization, rising housing costs, and fragmented local governance can worsen this disconnect.

Education and Spatial Inequality

Education is one of the most influential services shaping life trajectories. Unequal access to high-quality schools correlates strongly with residential patterns. In many metropolitan areas, school funding is tied to local property taxes, producing substantial disparities between affluent districts and lower-income neighborhoods. These spatial patterns reinforce cycles of advantage when well-resourced schools attract higher-income residents and strengthen property values.

Factors Shaping Access to Schools

Residential segregation, both historical and contemporary

School district boundaries that reflect and reinforce socioeconomic divides

Transportation availability, affecting whether students can attend schools outside their immediate neighborhood

Local policy decisions, including zoning that regulates housing types and affordability

These disparities influence not just educational outcomes but also long-term opportunities such as college access, employment options, and economic mobility.

Health Care Accessibility

Urban health outcomes reflect differences in the availability and quality of health care services. Communities lacking clinics, hospitals, and specialized providers often experience higher rates of chronic disease and lower life expectancy. Distance, cost, and insufficient insurance coverage add additional barriers. Geographic clusters of limited access, sometimes called medical deserts, mirror broader patterns of income inequality and racial segregation.

Components Affecting Health Care Access

Distribution of medical facilities across neighborhoods

Transportation connections to hospitals and clinics

Availability of preventive services, such as regular screenings

Environmental conditions, including exposure to pollution or lack of green space

Urban planners increasingly consider health equity by integrating clinics into underserved areas and improving transit to major medical centers.

Food Access and Urban Nutrition

Access to affordable, nutritious food is another essential urban service. Areas lacking grocery stores, fresh produce, and affordable options are often referred to as food deserts. These areas frequently overlap with low-income or minority communities, contributing to poorer health outcomes and reduced dietary variety.

In many metropolitan areas, school funding is tied to local property taxes, producing substantial disparities between affluent districts and lower-income neighborhoods.

INSERT IMAGE HERE after the correct sentence (as identified):

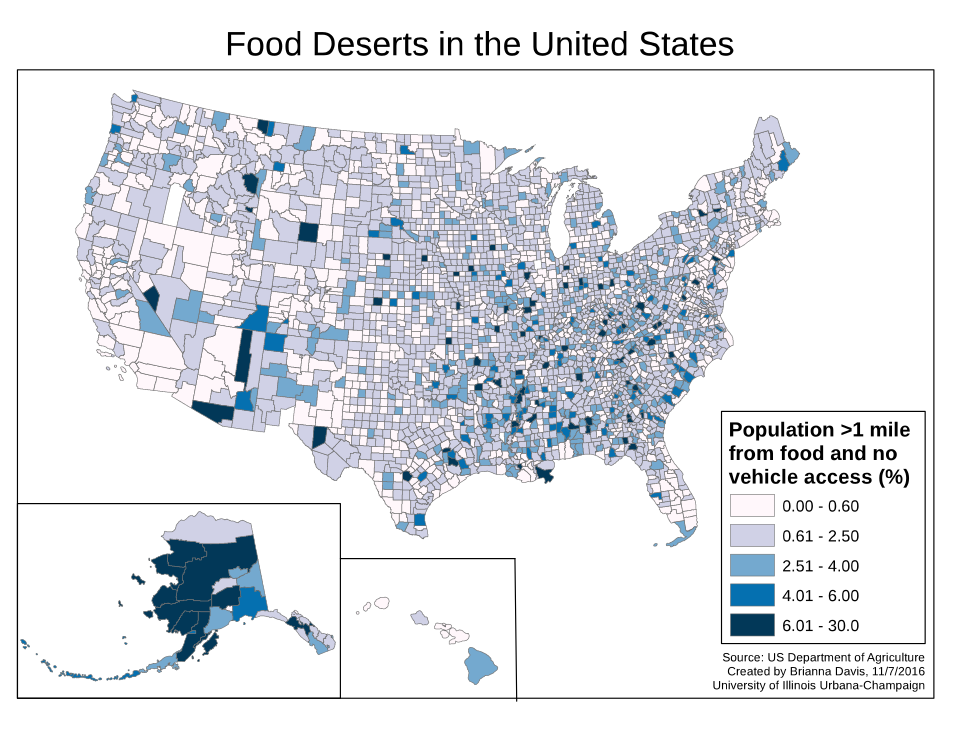

“In many metropolitan areas, low-income and minority neighborhoods are more likely to be food deserts, with few full-service supermarkets and many fast-food or convenience stores.”

Choropleth map showing U.S. counties where higher shares of residents live far from supermarkets, highlighting regional disparities in healthy food access. Darker colors indicate more severe food deserts. Though national in scale, it clearly visualizes spatial inequality relevant to urban access challenges. Source.

Food Desert: An area where residents have limited access to affordable and nutritious food, particularly fresh fruits and vegetables.

Food access is shaped by market decisions, transportation availability, land use patterns, and zoning that affects where grocery stores can locate. Expanding farmers markets, community gardens, and urban agriculture can partially address these deficits, while still depending on stable land tenure and supportive policy environments.

Public Space, Parks, and Green Infrastructure

Access to parks, playgrounds, recreational facilities, and broader green infrastructure contributes to physical health, social interaction, and mental well-being. Uneven distribution of parkland often leaves formerly industrial or historically redlined neighborhoods with fewer or lower-quality recreational spaces. As cities redevelop, new parks can improve neighborhood quality but may also contribute to green gentrification, where rising housing costs displace longtime residents.

Determinants of Park Access

Historical land-use patterns, including industrial legacies

Local investment priorities and political influence

Proximity to safe walking and transportation routes

Population density, affecting park crowding and facility needs

Park access is increasingly analyzed through equity frameworks that measure whether all residents can reach safe, high-quality recreational spaces within a reasonable distance.

Transportation and Mobility

Reliable transportation is one of the most crucial foundations of opportunity in urban areas. When residents lack access to bus routes, subway lines, or safe walking and biking infrastructure, they face reduced access to jobs, schools, medical care, and food options. This barrier can perpetuate spatial mismatch, where job growth occurs far from low-income neighborhoods without adequate transit connections.

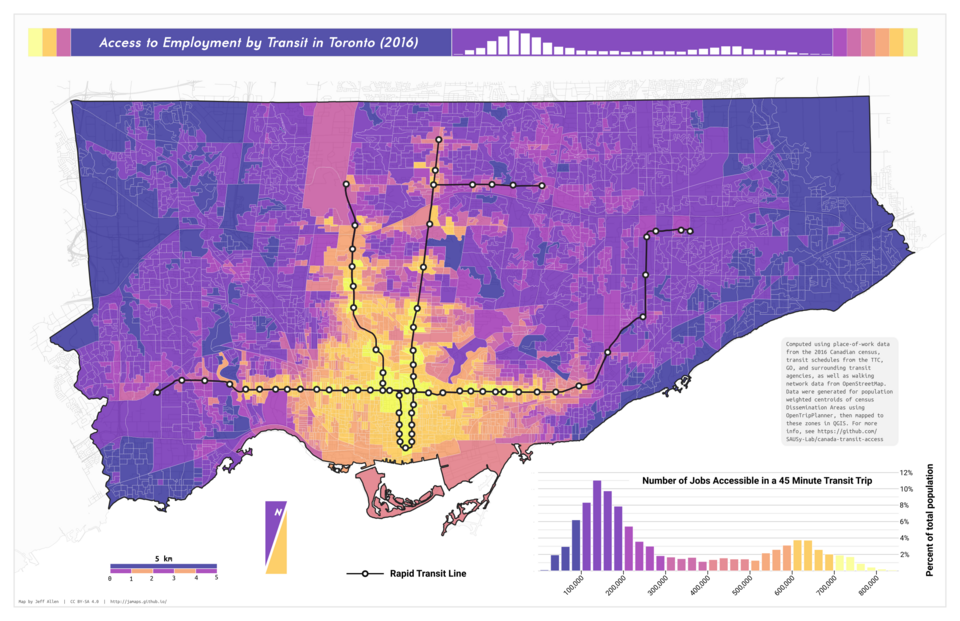

Because many urban residents do not own cars, public transit accessibility heavily shapes their ability to reach jobs, schools, and healthcare.

Heatmap showing how many jobs can be reached from different Toronto neighborhoods via public transit. Warmer colors represent higher job accessibility, illustrating how transit networks shape economic opportunity. Extra methodological detail on the page exceeds AP requirements but strengthens conceptual understanding of access patterns. Source.

Transportation Barriers and Impacts

Limited transit routes that bypass underserved neighborhoods

Infrequent service that increases travel times

High transportation costs, including fares or car ownership

Unsafe pedestrian environments that restrict access to nearby services

Improving transportation access can substantially expand opportunities by reducing commute times, connecting residents to regional labor markets, and enabling participation in civic life.

Intersections of Service Access and Opportunity

Limited access to any single service rarely occurs in isolation. Instead, multiple disadvantages often cluster spatially, creating cumulative disadvantage. Neighborhoods with limited transportation options typically also face shortages in food access, health care, and parks. These overlapping challenges reduce social mobility and shape long-term demographic trends as families move in search of better opportunities or experience forced displacement due to rising costs in more desirable areas.

Understanding these patterns enables urban geographers and policymakers to identify areas most in need of intervention and to design strategies that improve equitable access across all urban residents.

FAQ

Historic zoning laws, redlining, and industrial placement often determined which neighbourhoods received investment and which did not.

Over time, these early decisions produced long-term disparities in service provision.

• Wealthier areas attracted better schools, healthcare facilities, and infrastructure.

• Marginalised areas faced disinvestment, making it harder to improve access even when policies changed.

These patterns persist because infrastructure and services are expensive to relocate or rebuild.

Transport systems commonly prioritise routes that serve central business districts or affluent commuter areas.

This can leave peripheral or lower-income neighbourhoods with infrequent, indirect, or costly services.

• Poor connectivity increases travel time to jobs and services.

• Limited evening or weekend service restricts access for shift workers.

As a result, public transport can unintentionally deepen disparities rather than bridge them.

Businesses locate services where they expect strong financial return, which often aligns with higher-income areas.

In neighbourhoods perceived as less profitable, supermarkets, clinics, or pharmacies may be unwilling to invest.

• This creates service gaps that public agencies may struggle to fill.

• Market-driven location decisions can reinforce patterns of opportunity and deprivation.

Thus, private-sector choices significantly influence spatial inequalities.

Internet access affects residents’ ability to engage in education, employment, and public services.

Areas with poor broadband service face barriers in applying for jobs, accessing telehealth, or completing schoolwork.

• Digital exclusion often overlaps with existing socioeconomic inequalities.

• Public Wi-Fi or community technology hubs can help, but coverage is inconsistent.

Digital access has become essential for full participation in urban life.

Cities can target investment toward underserved neighbourhoods, prioritising areas with limited existing green space.

Common strategies include:

• Acquiring vacant land for new parks.

• Upgrading facilities in older or neglected parks.

• Improving walking routes, lighting, and safety to increase accessibility.

Partnerships with community groups can help ensure that redevelopment meets local needs and avoids creating pressure that leads to displacement.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain what is meant by unequal access to services in an urban area. Use one example of a service to support your answer.

Mark scheme

• 1 mark for a basic definition of unequal access (e.g., some neighbourhoods having fewer or lower-quality services).

• 1 mark for identifying a relevant urban service (e.g., healthcare, schools, public transport).

• 1 mark for explaining how access to that service varies spatially within a city.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using examples, analyse how differences in access to services and opportunities can influence social and economic outcomes for urban residents.

Mark scheme

• 1 mark for identifying at least one service or opportunity (e.g., employment, food access, green space).

• 1–2 marks for describing how spatial differences in access occur (e.g., transport networks, historical segregation, investment patterns).

• 1–2 marks for explaining social impacts (e.g., health inequalities, reduced quality of life, educational disparities).

• 1–2 marks for explaining economic impacts (e.g., limited job access, higher transport costs, restricted mobility).

• Maximum 6 marks awarded for well-developed, geographically accurate analysis using examples.