AP Syllabus focus:

‘Urban renewal and gentrification can bring both benefits and harms, while fragmented local governments can make coordinated solutions difficult.’

Urban renewal, gentrification, and fragmented governance reshape cities by altering neighborhood investment, resident composition, and the ability of governments to coordinate equitable, long-term urban development.

Urban Renewal: Purpose, Processes, and Effects

Urban renewal refers to government-led efforts to revitalize deteriorated urban areas through redevelopment, infrastructure upgrades, and new economic activity. These initiatives seek to reverse disinvestment and improve the built environment, yet their outcomes vary widely across cities and population groups.

Key Features of Urban Renewal

Urban renewal projects often involve multiple components that reshape land use and local housing conditions.

A large urban renewal project at Green Square in Sydney shows new high-density residential and commercial development replacing older land uses. The dense construction and active streetscape illustrate how renewal attracts new investment and reshapes urban form. The image includes more architectural detail than required by the syllabus but clearly supports the concept of redevelopment in aging city districts. Source.

Redevelopment of aging structures into new housing, commercial spaces, or public facilities.

Infrastructure upgrades, including transportation routes, utilities, and public amenities.

Public–private partnerships, where governments collaborate with developers to stimulate investment.

Zoning or land-use changes enabling higher-density or mixed-use redevelopment in declining districts.

Social and Economic Impacts

Although designed to catalyze economic growth, urban renewal frequently produces uneven outcomes.

Benefits may include improved housing quality, increased tax revenues, new job opportunities, and enhanced public spaces.

Harms may include displacement of long-term residents, loss of affordable housing, and the disruption of community institutions.

Gentrification: Patterns, Drivers, and Consequences

Gentrification is the process in which higher-income residents move into previously lower-income neighborhoods, raising property values and altering the social and cultural landscape.

Gentrification: A process of neighborhood change in which rising investment and higher-income in-movers increase property values and displace lower-income residents.

Gentrification is often linked to urban renewal initiatives but can also arise organically through market forces, cultural shifts, or broader patterns of urban resurgence.

Drivers of Gentrification

Public investment such as transit expansions or streetscape improvements that attract developers and new residents.

Private real estate speculation, responding to demand for walkable, centrally located neighborhoods.

Lifestyle preferences among young professionals seeking urban amenities, historic buildings, and short commutes.

Limited housing supply in high-demand metropolitan areas, pushing households toward formerly disinvested areas.

A neighborhood experiencing gentrification undergoes changes in housing stock, commercial activity, and demographic composition, often generating tensions surrounding affordability and cultural identity.

Consequences for Urban Communities

Gentrification produces a mix of benefits and harms, reflecting the complexity highlighted by the AP specification.

Benefits: reinvestment, declining vacancy rates, improved services, reduced crime, and increased local economic vitality.

Harms: displacement of long-term residents, rising rents, reduced diversity, cultural erosion, and pressure on community organizations.

Some cities attempt to mitigate harm through policies such as inclusionary zoning, rent stabilization, or community land trusts. However, these strategies require coordinated governance, which is often difficult to achieve.

Fragmented Governance: Challenges in Urban Policy Coordination

Fragmented governance describes a metropolitan region divided among many municipalities, agencies, and special districts, each with its own decision-making authority. This fragmentation influences how cities manage urban renewal and respond to gentrification.

Fragmented Governance: A system in which multiple overlapping local governments share authority within a metropolitan area, complicating coordinated policy actions.

Fragmentation produces uneven policies across jurisdictions and limits the ability to address regional problems—particularly housing affordability, transportation, and land-use planning.

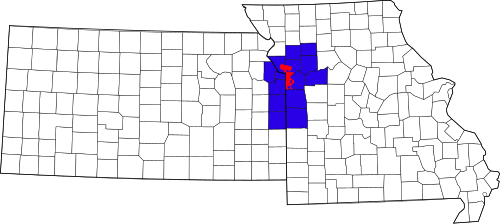

This map of the Kansas City metropolitan area illustrates how a single urban region spans many separate local jurisdictions. Each county and municipality maintains its own planning authority, complicating coordinated responses to housing, transportation, and redevelopment challenges. The map includes county-level detail not required by the syllabus but clearly conveys fragmented governance. Source.

Sources of Governing Fragmentation

Multiple municipalities within metropolitan areas with separate tax bases and political priorities.

County governments, school districts, and special-purpose districts operating independently of city governments.

Competitive economic development strategies, encouraging localities to prioritize their own tax revenue over regional needs.

Different local governments may support or resist redevelopment, leading to varied responses to growth pressures and uneven implementation of sustainability or equity initiatives.

Consequences for Urban Development

Fragmented governance shapes urban renewal and gentrification in several ways:

Inconsistent land-use policies across municipalities can create competition for development, encouraging suburban expansion while leaving central cities to manage affordability pressures alone.

Limited coordination of transportation and housing policy reduces the effectiveness of regional planning efforts such as transit-oriented development or affordable housing distribution.

Uneven service provision, where wealthier municipalities may have stronger infrastructure and amenities, deepening social and spatial inequalities.

Challenges in managing displacement, because no single authority oversees housing markets or sets regional affordability requirements.

A key difficulty is that while urban change often occurs at a metropolitan scale, decision-making remains local and fragmented. This structural mismatch contributes to the ongoing struggles of cities to address displacement, guide equitable redevelopment, and coordinate long-term planning.

Interconnections: Linking Renewal, Gentrification, and Governance

Urban renewal, gentrification, and fragmented governance intersect to shape how neighborhoods evolve. Redevelopment can spark gentrification, but governance fragmentation determines whether cities can manage its impacts. Local governments may pursue redevelopment to attract investment, yet without regional coordination, affordability strategies remain uneven and often ineffective. Understanding these relationships is essential for analyzing how urban change produces both benefits and harms—exactly as emphasized by the AP Human Geography specification.

FAQ

Cities often combine incentives for development with requirements that protect existing residents. These may include setting aside affordable units in redeveloped buildings or offering tax relief to long-term homeowners at risk of rising property costs.

Some local authorities also support community-led solutions such as land trusts, which keep housing permanently affordable while still allowing neighbourhood improvements.

Neighbourhoods with strong transit access, historic housing stock, or proximity to employment centres tend to gentrify faster because they attract higher-income in-movers.

Areas with weaker infrastructure, fewer amenities, or more industrial land uses may experience slower reinvestment or remain excluded from redevelopment cycles.

Local councils often promote policies that align with their electorate’s preferences, leading to divergent approaches to planning, housing, and economic development.

This can create policy patchworks across a metropolitan area, with some jurisdictions actively encouraging redevelopment and others resisting density or affordable housing.

When multiple jurisdictions share a metropolitan area, services such as transport, schooling, and utilities may be planned independently. This can produce gaps or overlaps in provision.

Uneven service availability can widen social inequalities if renewed areas receive upgraded services while neighbouring districts do not.

Community groups can advocate for resident protections, negotiate community benefits agreements, and pressure local authorities to include affordable housing in redevelopment plans.

They may also document cultural heritage, influence zoning decisions, or mobilise residents to participate in planning meetings, shaping how renewal affects neighbourhood identity.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which fragmented governance can make it difficult for cities to address gentrification-related displacement.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark for identifying a valid impact of fragmented governance.

1–2 additional marks for explaining how this impact makes managing displacement more difficult.

Acceptable points include:

Multiple municipalities may implement inconsistent housing policies (1 mark), which prevents a coordinated regional affordability strategy (1–2 marks).

Overlapping agencies may compete for investment (1 mark), reducing focus on protecting vulnerable residents (1–2 marks).

Lack of a single authority (1 mark) leads to fragmented data, planning, and eviction prevention resources (1–2 marks).

Maximum 3 marks.

(4–6 marks)

Using an urban example of your choice, evaluate how urban renewal can generate both benefits and harms for local communities. Your answer should refer to social, economic, and spatial impacts.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award up to 6 marks using the following guidance:

1–2 marks:

Identifies benefits of urban renewal (e.g., improved infrastructure, increased investment, reduced vacancy, economic revitalisation).

Identifies harms (e.g., displacement, rising housing costs, loss of cultural identity).

3–4 marks:

Provides developed explanations of at least one benefit and one harm, linked to a real urban example.

Shows clear understanding of how social, economic, or spatial change results from renewal.

5–6 marks:

Offers evaluative judgement on the extent to which urban renewal is beneficial or harmful.

Integrates the example effectively, showing depth (e.g., variation across neighbourhood groups, uneven impacts).

Demonstrates conceptual accuracy, using terms such as gentrification, reinvestment, or land-use change appropriately.

Maximum 6 marks.