AP Syllabus focus:

‘The Burgess model explains internal city structure as a series of concentric zones that reflect growth, industry, and residential patterns.’

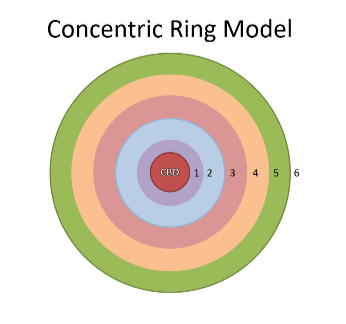

The Burgess Concentric-Zone Model illustrates how cities grow outward in rings from a central point, showing how land use, housing, and socioeconomic patterns evolve over time.

The Burgess Concentric-Zone Model: Core Ideas

The Burgess Concentric-Zone Model is an early 20th-century urban model that proposes cities develop in circular zones expanding outward from a central business district (CBD). Created by sociologist Ernest Burgess in 1925, the model reflects industrial-era American urbanization and highlights how competition for space, transportation costs, and socioeconomic factors shape land use.

Diagram of the Burgess Concentric-Zone Model showing five concentric rings of urban land use around the central business district (CBD). Each ring is labeled to distinguish the CBD, factory zone, zone of transition, working-class homes, residential zone, and commuter zone. This visualization supports the syllabus emphasis on how internal city structure can be modeled as concentric zones reflecting growth, industry, and residential patterns. Source.

Historical Context and Purpose of the Model

Burgess developed his model while studying Chicago, a rapidly industrializing city whose growth patterns suggested that urban expansion often follows outward radiating waves. His goal was to explain how social groups locate themselves within an urban area based on accessibility, economic status, and land values.

Theoretical Assumptions Underlying the Model

Burgess assumed that urban land is relatively flat, transportation routes radiate outward, and populations move progressively away from the city center as cities grow. These assumptions support the idea that zones form through invasion and succession, a pattern in which new land uses or social groups replace older ones nearer to the center.

Invasion and Succession: A process describing how new populations or land uses replace existing ones in urban areas as growth pressure pushes outward.

This assumption helps explain why certain housing types, industrial activities, and demographic groups are clustered in predictable rings.

Components of the Concentric-Zone Model

The Burgess model divides the city into five distinct zones, each shaped by accessibility, land values, and socioeconomic conditions.

Zone 1: Central Business District (CBD)

The CBD is the commercial and economic core of the city. It contains high-density office buildings, retail, and transportation hubs. Land values are highest here due to accessibility.

Central Business District (CBD): The dense commercial center of a city containing major businesses, services, and transportation connections.

Businesses cluster in the CBD to maximize visibility and minimize commuting distances for workers and consumers.

Zone 2: Zone of Transition

Surrounding the CBD is the zone of transition, characterized by mixed land use, aging housing, and light industry. Residential areas in this zone often include recent immigrants, lower-income groups, and small-scale manufacturing. The zone of transition experiences constant land-use pressure as economic activities expand outward from the CBD.

Zone 3: Zone of Independent Workers’ Homes

This zone contains modest working-class housing. Residents typically have stable employment and seek proximity to industrial jobs located in inner zones. Housing densities remain high, but the environment is more residential and less industrial than the zone of transition.

Zone 4: Zone of Better Residences

This zone reflects outward movement of middle-class families seeking larger homes, cleaner air, and greater separation from industrial activity. As transportation improved, this zone expanded because commuting became easier.

Zone 5: Commuter Zone

The outermost ring is the commuter zone, where residents live in low-density, single-family housing and travel longer distances to the urban core for work. This zone represents suburbanization trends that began during Burgess’s era and expanded dramatically in later decades.

Adapted concentric-zone diagram illustrating five rings of urban land use: inner city, zone of transition, working-class housing, suburbs, and an outer exurban/commuter ring. The labeled rings reinforce how residential areas generally become less dense and more affluent with distance from the urban core, supporting the model’s explanation of internal city structure. The inclusion of “exurbs” slightly extends the original model by highlighting very low-density outer residential areas not explicitly required by the syllabus but conceptually similar to the commuter zone. Source.

Processes That Shape Zone Formation

The Burgess model emphasizes spatial patterns driven by accessibility, land values, and social dynamics. Key processes include:

Competition for land, with high-value uses clustering near the center.

Spatial segregation as income groups separate based on housing affordability and access needs.

Invasion and succession, replacing land uses and populations over time.

Outward expansion, as cities grow and older areas transition to new functions.

Industrial pressures, pushing residential areas outward to avoid pollution and congestion.

Each process reflects how economic and social forces continually restructure urban space.

Strengths and Usefulness of the Burgess Model

Although developed nearly a century ago, the Burgess model remains foundational in urban geography because it highlights relationships between land value, accessibility, and residential patterns. The model is especially useful for understanding industrial cities experiencing rapid immigration, centralized employment, and limited transportation options.

Urban geographers use the Burgess model to introduce broader concepts such as:

Socioeconomic gradients

Bid-rent theory influences on land use

Segregation and neighborhood transitions

Historical patterns of inner-city decline and suburban growth

The model also offers a framework for comparing historical and contemporary city patterns, even when modern cities deviate from its idealized rings.

Limitations and Critiques of the Burgess Model

Despite its influence, the Burgess model has limitations when applied across different cities or time periods. Key critiques include:

It assumes uniform physical geography, ignoring rivers, hills, and coastlines.

It does not account for transportation corridors, which can shape development in sectors rather than rings.

It reflects industrial-era socioeconomic conditions, which do not match modern postindustrial cities.

It overlooks ethnic and cultural factors that influence residential clustering.

It assumes that cities evolve in orderly, predictable stages, which often does not occur.

Nonetheless, these critiques help students understand why later models—such as the Hoyt Sector Model and Harris and Ullman Multiple-Nuclei Model—expanded upon Burgess’s foundational work.

FAQ

The Burgess Model introduced the idea that land uses follow predictable spatial patterns shaped by accessibility and social factors. Later models adapted this logic but revised its assumptions.

The Hoyt Sector Model redirected attention to transportation corridors rather than rings, while the Multiple-Nuclei Model challenged the idea of a single core altogether. Despite their differences, both models retain Burgess’s premise that competition and economic patterns drive urban form.

Chicago’s rapid industrial growth, flat topography, and clear radial transport routes made its spatial structure ideal for observing ring-like development.

The city also experienced heavy immigration and social stratification, creating visible transitions between residential and industrial areas. These conditions helped Burgess identify repeating spatial sequences typical of early 20th-century industrial cities.

Researchers might use:

• Census data showing income gradients and population densities

• Housing age and value maps

• Commuting patterns revealing dependence on urban cores

• Land-use inventories showing industrial clustering

These data sets can highlight whether a city's social and economic patterns still form ring-like structures or whether modern decentralisation has altered them.

Even before widespread car use, improved public transport enabled households to move outward. Streetcars, rail lines, and later buses extended commuting ranges beyond walking distance.

Middle-income families sought cleaner, quieter neighbourhoods farther from industry. These transport improvements helped expand the outer residential rings and reinforced socio-economic sorting within the model.

Cities with complex physical geography—coastlines, mountains, rivers—or those shaped heavily by colonial planning tend not to form clear rings.

Highly decentralised economies with multiple employment centres also break the single-core assumption. Additionally, cities developed after the rise of car-based suburbs often show fragmented or polycentric patterns instead of concentric ones.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Explain one way in which the Burgess Concentric-Zone Model accounts for the distribution of lower-income residential areas within a city.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for identifying that lower-income groups are typically located in the zone of transition near the CBD.

• 1 mark for explaining why, such as proximity to industrial employment, lower housing quality, or cheaper land values due to congestion and pollution.

Question 2 (5 marks)

Using the Burgess Concentric-Zone Model, analyse how urban growth processes can lead to changes in the spatial distribution of social groups within a city.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for describing outward urban expansion as cities grow over time.

• 1 mark for identifying the process of invasion and succession affecting inner-city zones.

• 1 mark for explaining how middle- or higher-income groups move outward seeking larger homes or cleaner environments.

• 1 mark for linking industrial growth or land-use pressure to transitions in the zone of transition.

• 1 mark for demonstrating how these processes alter the social and economic composition of the rings as the city evolves.