AP Syllabus focus:

‘African city models reflect colonial influence, informal economies, and rapid urban growth; all models have limits when applied across places and times.’

African urban models illustrate how colonial history, informal economic activity, and rapid population growth shape city structure, while highlighting why urban models struggle to capture diverse, evolving urban realities.

Urban Models in Africa

African cities share broad structural patterns shaped by colonial legacies, rapid urbanization, and large informal sectors, yet each city remains highly distinctive. AP Human Geography emphasizes how these common features produce recognizable spatial forms while presenting challenges for traditional Western-centered models.

Colonial Imprints on Urban Structure

Colonialism profoundly shaped African cities’ early form and long-term land-use patterns. European powers established administrative, commercial, and settler districts planned for control and resource extraction.

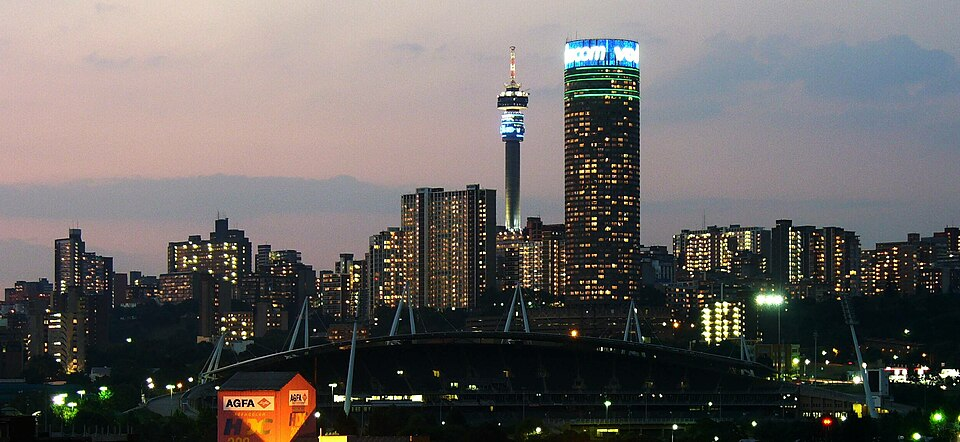

Evening skyline of central Johannesburg, showing dense commercial development typical of a major CBD. Such cores grew from colonial and postcolonial investment in administrative and financial functions. The image focuses on one CBD and does not display surrounding neighborhoods or informal settlements found in the African City Model. Source.

Many colonial cities developed dual urban cores: a European-designed CBD and an adjacent indigenous market or traditional center.

Colonial planning often created segregated residential districts that limited African populations’ mobility and access to urban services.

Post-independence growth expanded around these imposed frameworks, producing hybrid landscapes where older layouts coexist with newer informal development.

The African City Model

The African City Model (also known as the De Blij Model) seeks to represent structural patterns found in many Sub-Saharan African cities.

African City Model: A generalized representation of Sub-Saharan African urban structure emphasizing multiple CBDs, surrounding ethnic and mixed-use zones, and extensive peripheral informal settlements.

The model includes several characteristic spatial features:

A complex CBD, usually divided into colonial-era offices, a traditional market sector, and an emerging modern business district.

Ethnic and mixed residential zones extending outward, historically shaped by colonial segregation and cultural clustering.

Mining or industrial zones often connected to early resource-extraction activities.

Informal settlements and squatter areas forming rapidly at the urban periphery due to population growth, housing shortages, and limited formal planning.

These elements help explain how economic functions, migration flows, and land scarcity shape African cities’ internal geography.

Informal Economies and Peripheral Growth

African urbanization frequently occurs faster than governments can regulate housing or infrastructure. This produces extensive informal development that becomes a defining feature of many metropolitan regions.

Informal housing emerges where land is inexpensive or unregulated, forming dense peripheral settlements that lack formal services.

Aerial photograph of Kibera illustrating dense informal development where housing expands rapidly with limited planning. The packed roofs and narrow pathways demonstrate spatial intensity and service challenges in informal economies. The image shows one settlement rather than an entire metropolitan region but clearly represents peripheral squatter areas described in urban models. Source.

Informal economies, involving small-scale trade and unregistered enterprises, occupy streets, markets, and neighborhood centers, significantly shaping land use.

Infrastructure development often lags behind population growth, reinforcing spatial inequality between central districts and outlying informal zones.

Informality’s scale challenges rigid land-use models by creating flexible, dynamic patterns that shift with demographics, livelihoods, and policy responses.

Rapid Urban Growth and Demographic Pressures

Sub-Saharan Africa has some of the world’s fastest-growing cities. High fertility rates, rural-to-urban migration, and youthful populations contribute to intense demand for housing, transportation, and services.

Rapid expansion stretches infrastructure networks and increases reliance on public transit, paratransit, and walking.

Land markets struggle to keep pace with population growth, expanding informal subdivisions.

Environmental pressures, including flooding and water scarcity, intensify as development spreads into vulnerable peripheral zones.

These dynamics shape land-use intensity and dictate how neighborhoods evolve, challenging static models.

Limitations of Applying Urban Models

Urban geographers use models to simplify complex realities, but Africa’s diversity reveals their limits. AP Human Geography emphasizes that all models have constraints, especially when applied across regions or historical contexts.

Diversity Across African Cities

African cities are not uniform, and differences in colonial histories, economic specialization, population size, and political systems produce varied spatial forms.

Some cities follow grid patterns established by European planners; others retain organic layouts shaped by precolonial political centers.

Resource-based economies create specialized industrial corridors that differ from service-oriented cities.

National development strategies influence whether suburban expansion, vertical growth, or peripheral informality dominates.

These variations mean no single model—African or otherwise—captures the full range of urban experiences.

Limits of Western-Centered Urban Models

Models such as Burgess, Hoyt, and Harris–Ullman were developed in Western industrial cities and often assume stable economies, regulated housing markets, and extensive infrastructure—conditions that differ from many African contexts.

Western models understate the significance of informal economies and unplanned expansion.

They assume centralized transportation networks rather than dispersed, flexible mobility systems.

They rely on predictable land-value gradients, whereas African land markets may blend customary tenure with formal property systems.

Between these mismatches, Western models may obscure rather than clarify African urban processes.

The Challenge of Rapid Change

Urban models struggle to keep pace with the speed of African urban transformation.

New settlements appear quickly and do not follow established patterns.

Infrastructure projects—such as new highways or satellite towns—can rapidly reorganize spatial structure.

Cities adapt to global economic shifts, climate risks, and demographic pressures in ways that make static models outdated.

Because spatial conditions evolve faster than models can represent, geographers must use models cautiously and revise them regularly.

Using Models Thoughtfully

Urban models remain valuable analytical tools if interpreted with appropriate context. In African settings, they help identify broad spatial tendencies—such as strong CBDs, peripheral informality, and colonial imprints—while requiring flexibility to account for immense variation and rapid change.

FAQ

Multiple CBDs emerged because precolonial market centres, colonial administrative districts, and post-independence commercial zones developed separately rather than replacing one another.

These centres often served different social groups and economic functions, and rather than merging, they expanded simultaneously.

In many cities, transport corridors linking these zones reinforced their distinctiveness, creating spatially fragmented but interdependent business districts.

Customary tenure systems, managed by local chiefs or community authorities, often coexist with formal land markets.

Because legal boundaries may be unclear, residents may settle informally with community permission but without state-recognised titles.

This dual governance makes formal planning difficult and contributes to rapid, informal expansion at the city’s edge.

Mining and industrial zones often formed along early transport routes—railways or roads built for resource extraction.

They developed as linear corridors rather than compact areas because:

Movement of raw materials required direct, efficient paths.

Colonial powers invested selectively in strategic routes, not in comprehensive urban infrastructure.

These wedges continue to attract related industries and labour activities, reinforcing their spatial pattern.

Migrants often settle near relatives or ethnic networks who provide housing access, employment connections, and social support.

These clusters expand outward from older neighbourhoods, maintaining cultural identity while adapting to urban settings.

In some cities, these patterns reduce relocation costs for newcomers but also reinforce historical socio-spatial divisions.

Informal economic activity shifts quickly across space, responding to population flows, new road construction, and fluctuations in market demand.

Because informal enterprises:

Do not require permits,

Occupy flexible spaces,

And relocate easily when displaced,

their distribution changes too rapidly for static models to capture accurately.

This dynamism contributes to the limited predictive value of fixed urban models in many African contexts.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which colonial planning has influenced the contemporary spatial structure of African cities.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a colonial influence, such as segregated residential zones or the establishment of a European-style CBD.

1 mark for explaining how this feature shaped urban land use today (e.g., persistent economic inequality, concentration of services in colonial cores).

1 mark for providing a clear geographical link to spatial structure (e.g., dual-city patterns, enduring location of administrative and commercial functions).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using the African City Model, assess the extent to which informal settlements challenge the applicability of traditional Western urban models in Sub-Saharan African cities.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for describing a key feature of the African City Model (e.g., multiple CBDs, peripheral informal settlements).

1 mark for identifying a characteristic of informal settlements (e.g., high density, lack of formal planning, informal economies).

1 mark for explaining why Western models struggle to account for informality (e.g., assumptions of regulated land markets or predictable residential patterns).

1–2 marks for assessing the extent of the challenge, with supported reasoning (e.g., rapid, unplanned growth contradicts fixed concentric or sector-based assumptions).

1 mark for a concluding judgement that directly answers the command term (e.g., stating whether informal settlements make Western models largely insufficient or only partially limited).