AP Syllabus focus:

‘Southeast Asian urban models emphasize colonial legacies, multiple business districts, and ethnic neighborhoods shaping land use patterns.’

Urban models in Southeast Asia illustrate how historical colonialism, diverse cultural landscapes, and polycentric economic development have produced distinctive spatial patterns unlike Western-centric models of internal city structure.

Southeast Asian Urban Structure: Core Characteristics

Southeast Asian cities share several spatial features shaped by historical, cultural, and economic processes. These characteristics distinguish them from models based on North American or European urban development.

Colonial Legacies in the Urban Landscape

Colonial rule significantly shaped the internal structure of cities such as Jakarta, Manila, Ho Chi Minh City, Hanoi, and Singapore. Colonial authorities often created segregated districts to separate European settlers from local populations, influencing present-day spatial organization.

European administrative districts were typically located near ports or strategic military sites.

Colonial-era commercial streets developed along docks, canals, or early transportation routes.

Infrastructure patterns—particularly wide boulevards, rail corridors, and civic buildings—still anchor major business districts.

Colonial Legacies: Long-term spatial, social, and economic patterns resulting from foreign colonial rule, visible in administrative centers, commercial cores, and segregated neighborhoods.

These legacies continue to influence where high-value land uses cluster and how new growth expands outward.

Multiple Business Districts and Polycentric Development

Unlike cities organized around a single central business district (CBD), Southeast Asian cities frequently exhibit polycentricity, meaning multiple commercial and service nodes develop across the metropolitan area. This pattern reflects rapid modernization, global investment, and uneven infrastructure development.

Key features include:

A historic CBD tied to colonial administration and early trade.

A modern CBD characterized by high-rise finance, technology, and corporate offices.

Emerging secondary business districts in suburban or peri-urban areas driven by new transit corridors and international investment.

Polycentric Development: A spatial pattern in which several business or activity nodes coexist, reducing reliance on a single urban core.

These multiple business districts influence commuting patterns, housing markets, and the spatial distribution of services.

Ethnic Neighborhoods and Cultural Spatial Patterns

Ethnic diversity strongly shapes the internal structure of many Southeast Asian cities. Historical migration—both regional and global—created differentiated residential and commercial enclaves.

Examples of common patterns include:

Chinese commercial districts, often near ports, markets, and warehousing zones.

Indian or South Asian neighborhoods, frequently associated with temple complexes, trade streets, and artisan activities.

Indigenous and local community clusters, where vernacular housing and small-scale commerce persist.

These ethnic enclaves are not only residential spaces but also important cultural, religious, and economic hubs. They contribute to the mixed land-use character typical of many Southeast Asian cities.

Mixed Land Use as a defining characteristic

Mixed land use—where residential, commercial, and industrial activities exist in close proximity—is more common than in many Western models.

Traditional shop-houses combine ground-floor commerce with upper-floor housing.

Street markets, temples, schools, and workshops share dense urban blocks.

Land-use zoning is often less rigid, supporting adaptive and informal economic activity.

The McGee Model of Southeast Asian Cities

Geographer T. G. McGee proposed one of the most influential models for Southeast Asian urban structure.

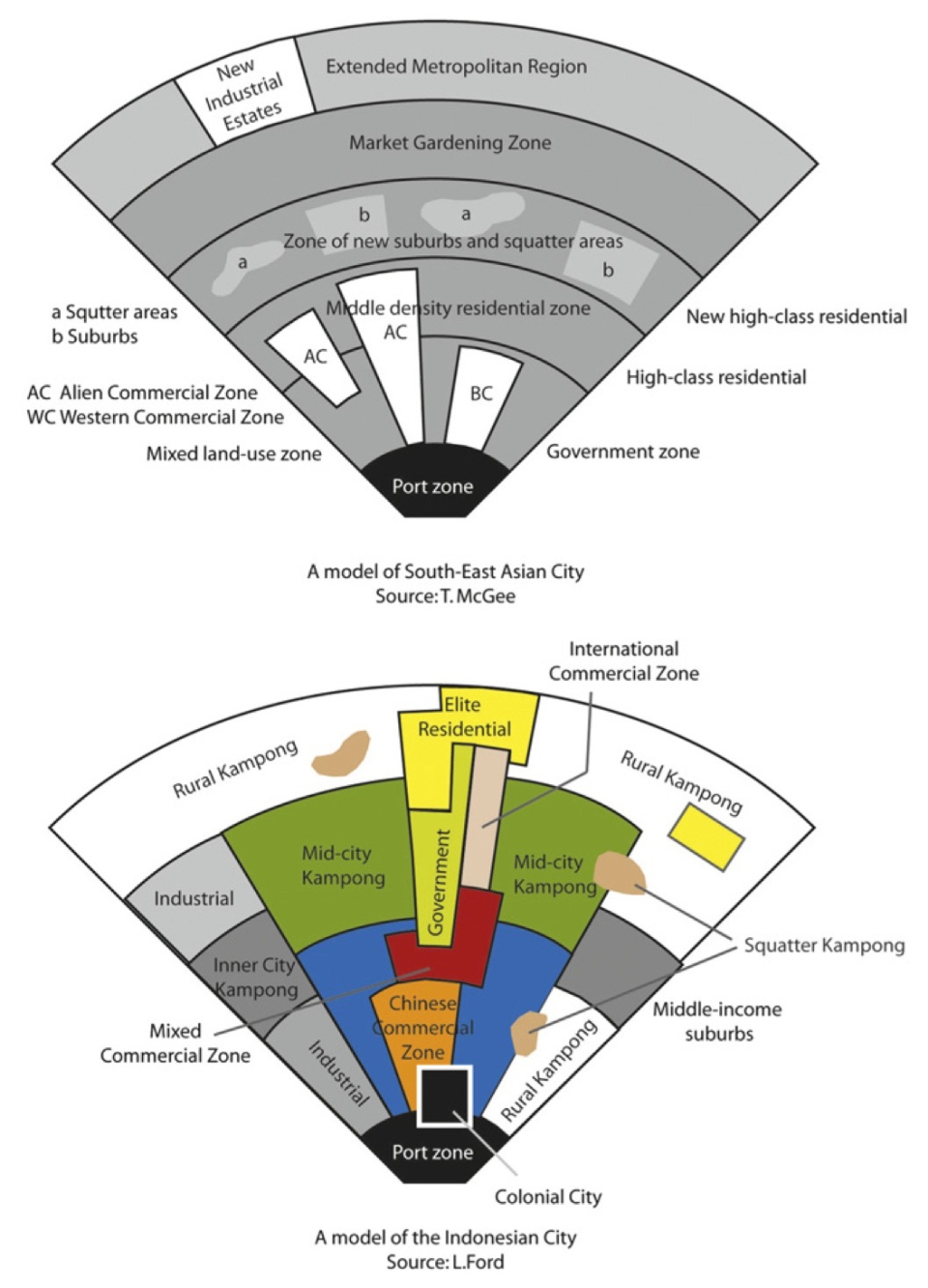

This diagram shows a generalized model of land-use areas in Southeast Asian cities, highlighting the port zone, commercial spine, and mixed-use and residential sectors. It visually reinforces the spatial elements of the McGee model discussed in the notes. The lower panel includes Indonesian-specific detail, which extends but does not contradict the required AP Human Geography content. Source.

Although not universally applicable, it identifies recurring spatial elements that help explain regional patterns.

Key Spatial Features in the McGee Model

A port zone that historically served as the economic backbone, reflecting maritime trade networks.

A commercial spine extending from the port inland, lined with shops, offices, and mixed-use development.

Alien commercial zones, often associated with ethnic Chinese business communities.

High-density residential sectors radiating outward around the commercial spine.

Peripheral informal settlements expanding at the metropolitan edges due to rapid population growth.

Informal Settlement: A residential area developed outside formal planning and regulation, typically featuring self-built housing and limited infrastructure access.

The McGee model captures the dynamic interaction between formal and informal development, global trade, and historical influences.

This aerial view of Ho Chi Minh City illustrates how the CBD clusters along a historic port zone, reflecting the enduring importance of maritime access in Southeast Asian urban structure. High-rise commercial towers sit adjacent to older mixed-use districts, demonstrating the blend of historic and modern land uses. The photo includes wider metropolitan context that supports understanding of urban spatial patterns. Source.

Infrastructure, Mobility, and Contemporary Urban Growth

Transportation networks continue to reshape land-use patterns in Southeast Asian cities. As highways, metro lines, and bus rapid transit systems expand, new residential and commercial clusters emerge along these routes.

Important drivers include:

Rapid population growth, increasing demand for housing and services.

Foreign investment, fueling new business districts and technology corridors.

Expanding port and airport facilities, reinforcing international economic connections.

However, these changes also produce challenges such as congestion, uneven development, and pressure on housing affordability.

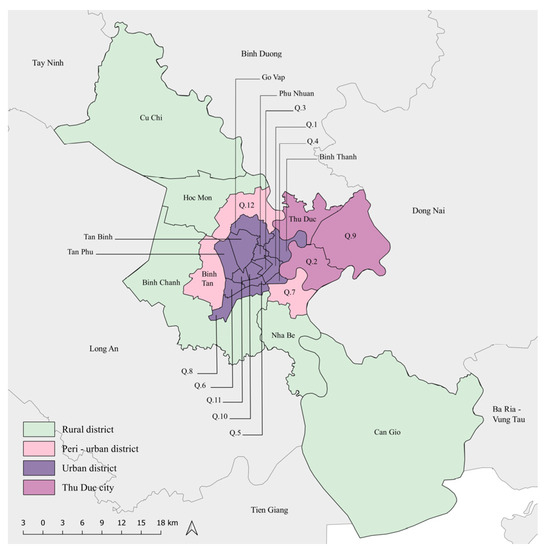

This map depicts Ho Chi Minh City’s urban, peri-urban, and rural districts, visualizing how the metropolitan region extends beyond the core city. It supports understanding of peripheral growth and spatial differentiation characteristic of Southeast Asian urban models. The map appears within a broader climate and planning study but includes only spatial categories relevant to the syllabus. Source.

Comparing Southeast Asian Models to Western Urban Models

Southeast Asian cities differ from Western-based models—such as the Burgess, Hoyt, or multiple-nuclei models—because:

Their development is strongly shaped by maritime trade and colonial histories.

Informal economies and mixed land use are more prominent.

Ethnic enclaves play a larger role in structuring urban space.

Rapid growth leads to greater peripheral expansion and more polycentric patterns.

These distinctions underscore why an understanding of Southeast Asian urban models is essential for analyzing global urban diversity and the spatial impacts of colonialism, ethnicity, and economic globalization.

FAQ

Pre-colonial maritime trade created early settlement nodes along sheltered harbours, rivers and coastal inlets. These locations offered natural access to regional trading networks long before European involvement.

Today, these same sites often remain valuable due to established transport corridors, waterfront commercial activity and dense surrounding populations. As a result, port-facing CBDs and mixed-use waterfront districts in cities like Manila and Jakarta still reflect spatial priorities that originated centuries earlier.

Ethnic districts often emerged from historical trade specialisation, where migrant groups controlled specific commodities or financial networks.

Their resilience is reinforced by:

Intergenerational business continuity

Strong cultural and linguistic networks

Concentrated ownership of shop-houses and market stalls

Religious and community institutions anchoring neighbourhood identity

These factors make ethnic commercial districts especially resistant to displacement even amid rapid redevelopment.

Informal transport, such as motorcycle taxis, jeepneys or minibuses, thrives in areas lacking formal public transit coverage.

These systems affect spatial patterns by:

Extending accessibility into narrow streets and peripheral settlements

Supporting decentralised commercial activity where formal routes are limited

Encouraging compact, mixed-use cluster development around informal stops

Their flexibility allows them to adapt rapidly to population growth and changing economic needs, reinforcing polycentric urban forms.

International migrants often enter labour markets in construction, domestic work, manufacturing and services, gravitating toward affordable inner-city or peri-urban areas.

Their presence contributes to:

New cultural landscapes through shops, eateries and religious venues

Shifts in housing density as shared accommodations proliferate

Transnational economic linkages, such as remittance-based businesses

These neighbourhoods can become dynamic multicultural zones that evolve beyond historic ethnic enclaves.

Peri-urban expansion is driven by intense population growth, limited affordable housing in central districts and rapid industrial development on metropolitan edges.

Additional contributing factors include:

Flexible or uneven enforcement of planning regulations

Land speculation along new highways and transit corridors

The presence of informal settlements that can expand quickly without formal infrastructure

This produces a transitional landscape where agriculture, industry and new housing coexist, making peri-urban space a defining feature of Southeast Asian urbanisation.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which colonial legacies have influenced the internal structure of Southeast Asian cities.

Mark scheme:

Award up to 3 marks:

1 mark for identifying a relevant colonial influence (e.g., creation of administrative districts, port-centred layouts, segregated neighbourhoods).

1 mark for describing how this influence appears in the modern urban landscape (e.g., continued concentration of government or commercial functions in former colonial cores).

1 mark for explaining why this influence persists today (e.g., infrastructure investment anchored development; colonial roads and buildings still structure land-use patterns).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using the McGee model, analyse how the spatial organisation of Southeast Asian cities reflects both historical processes and contemporary economic change.

Mark scheme:

Award up to 6 marks:

1 mark for identifying a key component of the McGee model (e.g., port zone, commercial spine, alien commercial zones, peripheral informal settlements).

1 mark for describing how historical processes such as maritime trade or colonial rule shaped early urban form.

1 mark for explaining how these historical features helped establish high-value commercial areas or ethnic business districts.

1 mark for identifying a contemporary economic force influencing spatial structure (e.g., foreign investment, creation of secondary CBDs, transport expansion).

1 mark for linking contemporary forces to specific spatial outcomes (e.g., growth of modern CBDs, emergence of polycentric patterns).

1 mark for overall analytical coherence showing how past and present processes interact to shape the current urban form.