AP Syllabus focus:

‘The Hoyt model describes how land use can form wedges or sectors along transportation routes and environmental corridors.’

The Hoyt Sector Model explains how urban land uses develop in elongated sectors shaped by transportation routes and environmental features, revealing distinct residential and economic patterns over time.

Understanding the Hoyt Sector Model

Developed by economist Homer Hoyt in 1939, the Hoyt Sector Model proposes that cities grow in wedge-shaped sectors rather than concentric rings. This framework helps geographers interpret how urban functions follow corridors of accessibility and desirability. Unlike earlier models, it emphasizes the directional expansion of land uses influenced by transportation and environmental conditions.

Core Principles of the Hoyt Model

The model centers on the idea that specific land uses—such as high-income housing, industry, and lower-income housing—expand outward from the Central Business District (CBD) in predictable sectors. These sectors often begin near the CBD and grow along rail lines, major roads, or natural features.

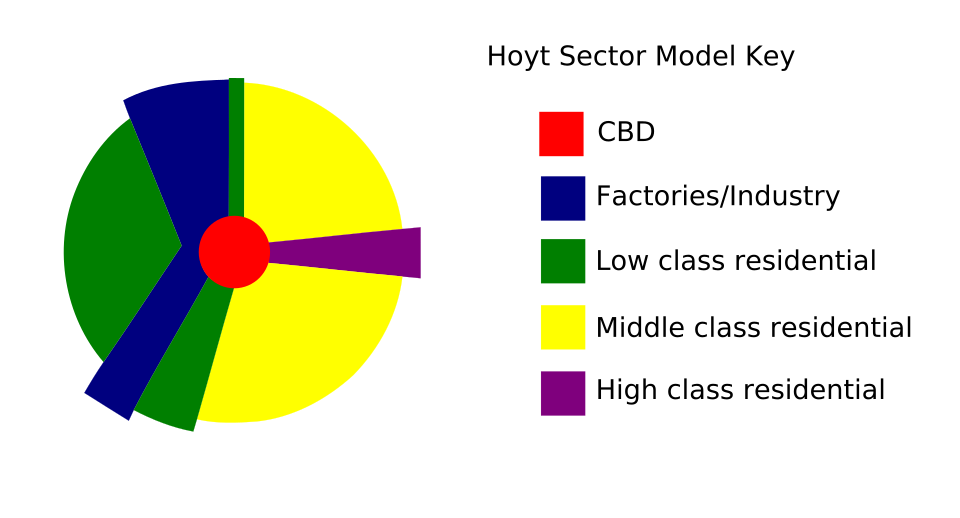

A simplified diagram of the Hoyt Sector Model, illustrating how land uses form wedge-shaped sectors extending outward from the CBD. The labeled sectors show transportation and industry, plus low-, middle-, and high-class residential areas aligned with accessibility corridors. This visual aligns directly with the urban spatial concepts emphasized in AP Human Geography. Source.

Central Business District (CBD): The commercial and administrative core of a city, characterized by high accessibility and concentration of services.

This spatial logic helps explain why land uses cluster in particular patterns and why certain sectors remain stable or intensify over long periods.

Transportation Corridors and Sector Formation

A defining feature of the Hoyt Model is that land uses align with transportation routes, which serve as conduits for movement and economic activity. Transportation access increases land desirability for certain uses while decreasing it for others, ultimately shaping sector growth.

How Transportation Shapes Sectors

Transportation routes reduce friction of distance and enhance connectivity, enabling residential and industrial land uses to organize around them.

Key pathways influencing sector development include:

Railways, which attract industrial and lower-income residential sectors due to accessibility and lower land costs.

Major roadways, which become desirable for middle- and high-income neighborhoods seeking mobility and reduced commute times.

Streetcar or rapid transit lines, which historically created elongated patterns of suburban residential growth.

As new infrastructure is added, sectors can extend or shift, illustrating the dynamic relationship between transportation investment and urban form.

Environmental Corridors and Land-Use Patterns

The model also recognizes the influence of environmental corridors, such as rivers, valleys, or areas with favorable microclimates. These factors shape where desirable housing clusters or where industrial activity avoids.

Environmental Factors Encouraging Sector Growth

Environmental corridors may:

Provide scenic amenities that attract high-income residential sectors.

Limit development, pushing land uses to grow in alternative directions.

Support industrial activity where waterways offer transport or cooling resources.

High-income sectors especially tend to follow environmental advantages, reinforcing the idea that residential desirability responds to both physical and infrastructural attributes.

Sector Types in the Hoyt Model

Each sector reflects socioeconomic and functional characteristics that align with transportation and environmental influences. These sectors can persist for decades due to path dependence, where previous land-use decisions shape future ones.

High-Income Residential Sectors

These sectors typically extend along:

Scenic corridors with environmental amenities

Major roads offering privacy and accessibility

Areas upwind of industrial zones, avoiding noise and pollution

Path Dependence: The tendency for urban spatial patterns to persist because past decisions constrain or guide future development.

High-income sectors often anchor schools, parks, and commercial services that reinforce their desirability.

Middle- and Low-Income Residential Sectors

Middle-income residential sectors commonly form adjacent to high-income areas but still benefit from transportation access. Low-income sectors usually develop:

Near industrial corridors

Along rail lines or highways

In areas with less environmental desirability

These patterns reflect housing affordability, proximity to employment, and historical barriers affecting residential choice.

Industrial and Transportation Sectors

Industry typically follows transportation routes offering efficient movement of goods. Industrial corridors emerge where:

Rail access is highest

Land prices are lower

Environmental constraints minimize conflict with residential uses

This alignment helps explain why industrial zones often radiate outward in narrow sectors from the CBD.

Strengths and Limitations of the Hoyt Model

The Hoyt Model remains influential because it highlights directional growth and the persistent importance of transportation. It also showcases how social and economic forces shape distinct residential geographies.

Strengths

Demonstrates how cities grow in response to transportation infrastructure

Accounts for environmental variation shaping residential desirability

Explains persistent socioeconomic clustering across urban space

Limitations

Although useful, the model oversimplifies modern metropolitan complexity. It does not fully incorporate:

Multiple nuclei or decentralized employment centers

Rapid suburbanization patterns

Variation across cultural or regional contexts

Despite these limitations, the Hoyt Sector Model remains a valuable framework for understanding how transportation and environment shape urban land-use sectors over time.

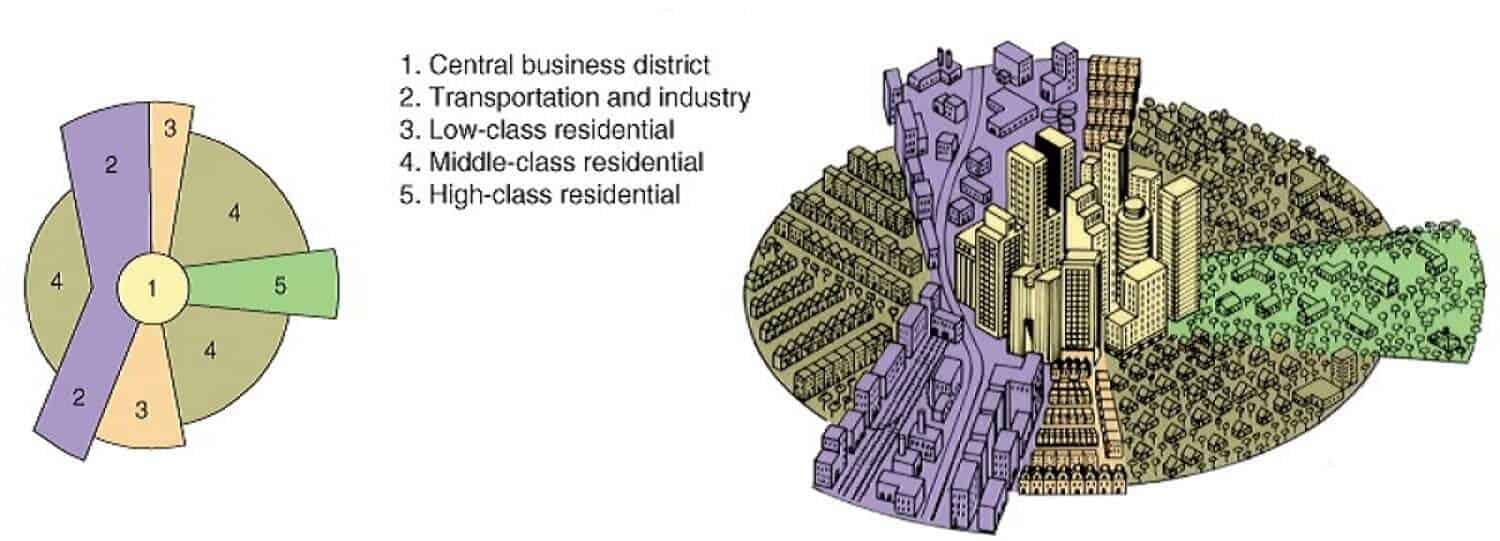

A two-part illustration of the Hoyt Sector Model showing both a color-coded 2D sector diagram and a 3D visual representation of industrial, low-, middle-, and high-class residential wedges radiating from the CBD. The labeled sectors highlight how land uses align with transportation and environmental corridors. This image reinforces the spatial logic of sector-based urban development without introducing unrelated models. Source.

FAQ

Hoyt developed the Sector Model through detailed housing price studies in early 20th-century American cities, especially Chicago. He observed that residential values tended to extend along transportation corridors rather than in uniform rings.

His research found consistent wedge-shaped patterns across streetcar suburbs, industrial districts, and elite residential avenues, suggesting a broader spatial logic that shaped many expanding industrial-era cities.

Sector boundaries persist because infrastructure investment, land values, and historical residential preferences reinforce existing patterns.

Factors maintaining stability include:

Long-lived transport routes that anchor growth

Schools, parks, and amenities concentrated in certain sectors

Social and economic inertia that encourages households to cluster near similar groups

These forces make sectors resistant to rapid change even as the city expands.

The model highlights how accessibility and desirability shape residential sorting, creating spatial advantages and disadvantages.

High-income sectors often enjoy superior amenities, cleaner environments, and better transport access.

Low-income sectors, aligned with industrial routes, may face higher exposure to pollution and fewer public services.

This spatial arrangement can reinforce long-term inequalities across generations.

New transport technologies can redirect growth by shifting accessibility patterns.

For example:

Motorways may create entirely new wedges of suburban development.

Rapid transit lines can elevate land values in previously underdeveloped sectors.

Deindustrialisation may reduce the importance of rail-based industrial corridors.

Such changes can produce hybrid or fragmented sectors that differ from Hoyt’s original, rail-oriented assumptions.

Cities may deviate from Hoyt’s expected sector shapes when environmental hazards constrain development.

Hazards such as floodplains, steep slopes, or contaminated land can:

Prevent high-income residential expansion even along major transport routes

Push industrial activities toward areas where risk is already present

Encourage compact sectors in safer or more stable zones

This results in sector patterns that reflect both human preferences and natural constraints.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain how transportation routes influence the development of sectors in the Hoyt Sector Model.

Question 1

Award marks for the following points:

1 mark: Identifies that transportation routes guide the outward growth of urban land uses in wedge-shaped sectors.

1 mark: Explains that land uses align along major transport corridors such as railways or roads due to increased accessibility.

1 mark: States that sectors develop in these directions because transport corridors reduce travel time and attract specific land uses (e.g., industry or residential areas).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using the Hoyt Sector Model, analyse why high-income residential areas and industrial zones often form in different sectors of a city. In your answer, refer to accessibility, environmental factors, and long-term urban development patterns.

Question 2

Award marks for the following points:

1 mark: States that high-income and industrial areas form in different sectors due to contrasting desirability and land-use needs.

1 mark: Explains that industry tends to cluster along transport corridors for efficient movement of goods.

1 mark: Explains that high-income residential areas avoid industrial zones due to pollution, noise, or visual disamenities.

1 mark: Describes how environmental amenities (e.g., scenic corridors, favourable microclimates) attract high-income residential development.

1 mark: Refers to path dependence, noting that once sectors develop in certain directions, future growth follows established patterns.

1 mark: Demonstrates understanding of how the Hoyt Model illustrates long-term spatial separation of social groups and economic functions.