AP Syllabus focus:

‘Latin American urban models highlight a strong central business district, elite residential sectors, and peripheral informal settlements.’

Urban models in Latin America illustrate how historical processes, socioeconomic inequality, and spatial structures shape the internal form of many regional cities, clarifying recurring land-use patterns.

Key Characteristics of Latin American Urban Structure

Latin American cities share several spatial features shaped by colonial legacies, economic inequality, and contemporary urban growth. The most widely referenced frameworks explain how cities concentrate formal activity in the center while extending wealth and poverty along distinct spatial corridors.

The Central Business District (CBD)

A defining feature is the strong central business district, which remains the economic, cultural, and administrative core. Unlike in some North American cities where CBDs have declined relative to suburbs, Latin American CBDs often remain vibrant, dense, and multifunctional.

Central Business District (CBD): The commercial and administrative heart of a city, typically characterized by dense land use, high property values, and major public institutions.

Because CBDs maintain symbolic and functional importance, they strongly influence the arrangement of residential and commercial sectors surrounding them. As cities modernized, secondary commercial spines extended outward from these cores, reinforcing existing spatial hierarchies.

Commercial Spine and Elite Residential Sector

Latin American urban models typically include a commercial spine radiating from the CBD. High-quality infrastructure, transportation, and amenities cluster along this corridor, attracting investment and reinforcing its economic significance. Running alongside the spine is an elite residential sector, which often includes high-income neighborhoods, gated communities, and luxury services.

Residential Sector: A zone of housing that shares common socioeconomic characteristics, shaped by land values, accessibility, and historical development patterns.

This spatial arrangement reflects colonial roots, when elites lived near central plazas and administrative buildings. Modern versions extend this pattern outward as wealthier residents seek both proximity to services and greater privacy afforded by suburban-style enclaves.

Peripheral Zones and Informal Settlements

Surrounding the core and elite sectors are peripheral informal settlements, commonly known as barriadas, favelas, or villas miseria, depending on the country. These areas expand rapidly due to migration, limited affordable housing, and uneven state investment.

Informal Settlement: A residential area developed without formal planning, legal tenure, or complete access to infrastructure and public services.

These zones typically emerge on the urban fringe, where land is cheaper but far from jobs and transit. Their growth demonstrates how inequality and population pressure shape spatial outcomes.

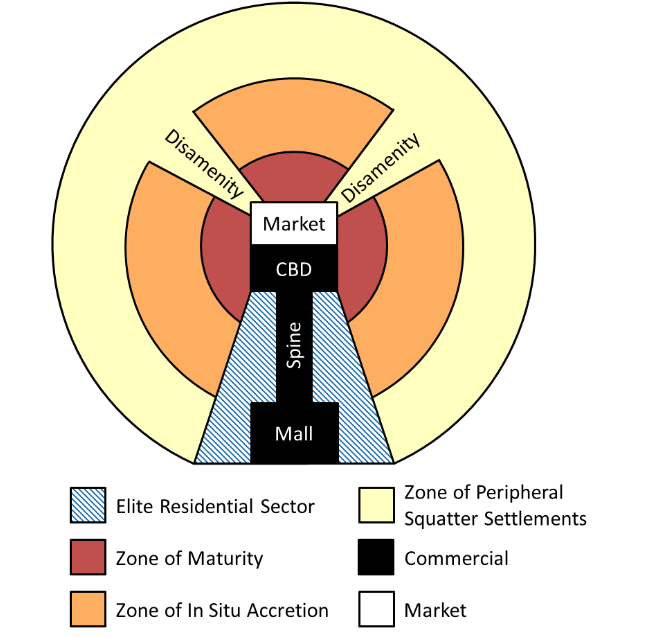

Model of a Latin American city showing a strong CBD, a commercial spine with an adjacent elite residential sector, surrounding middle-class zones, and peripheral informal settlements. Additional labeled features such as disamenity sectors extend beyond syllabus requirements but support spatial understanding. Source.

A normal sentence must follow any definition, and this one clarifies the role of informal settlements in illustrating the contrast between formal and informal urban growth.

Historical Foundations of the Model

Latin American city structure reflects Spanish and Portuguese colonial planning, especially the Laws of the Indies, which mandated orderly layouts with central plazas, administrative buildings, and religious institutions. This produced highly centralized urban cores that continue to organize contemporary land use.

Migration patterns intensified these structures. Rural-to-urban migration surged in the 20th century as industrialization created economic opportunities in cities. Because formal housing supply could not keep pace, informal settlements expanded outward, reinforcing a sharp socioeconomic gradient from center to periphery.

The Griffin–Ford Model

One of the most widely cited frameworks is the Griffin–Ford Latin American City Model, which synthesizes these recurring features.

Major Components of the Griffin–Ford Model

Strong CBD with high density, public transit access, and concentrated economic activity

Commercial spine extending outward from the CBD

Elite residential sector aligned with the spine

Zone of maturity, consisting of older, stable middle-class neighborhoods

Zone of in situ accretion, representing transitional areas with mixed-quality housing

Peripheral informal settlements, which absorb most new migrants and low-income residents

The model captures both continuity and change: colonial layouts endure, but modern forces—including globalization, transportation, and demographic shifts—shape how cities expand.

A hillside favela appears beside a wealthier district in Rio de Janeiro, illustrating the spatial proximity of informal and affluent neighborhoods common in Latin American cities. The contrast in building quality and infrastructure highlights socioeconomic disparities. Cultural landmarks visible in the background exceed syllabus requirements but contextualize the landscape. Source.

Socioeconomic and Spatial Dynamics

Inequality and Land Values

Latin American cities exhibit steep socioeconomic contrasts. Land near the spine and CBD has high value, reflecting accessibility and infrastructure investment. In contrast, peripheral areas often lack public utilities, transportation, and employment access, producing spatial inequality.

Urban Growth and Migration

Rapid population growth amplifies spatial disparities. Migration fuels the expansion of informal settlements, while redevelopment pressures reshape inner-city districts. As cities modernize, some formerly peripheral areas undergo gentrification, altering their demographic and economic profiles.

Transportation and Accessibility

Transportation networks reinforce the model’s spatial logic. High-quality transit and road corridors frequently align with the commercial spine and elite sectors, while peripheral areas rely on slower, less reliable systems. This contributes to longer commute times and lower mobility for low-income residents.

Contemporary Transformations

Latin American cities continue to evolve, but the core elements outlined in the syllabus remain relevant. Redevelopment projects may revitalize CBDs, while new commercial hubs emerge along expanded transportation corridors. Yet the persistent combination of central concentration, elite sectors, and peripheral informality continues to define the region’s urban morphology, making these models essential tools for understanding land-use patterns across Latin America.

FAQ

The Latin American model places far greater emphasis on a strong, vibrant CBD and a commercial spine, whereas many North American cities have experienced suburban decentralisation and edge-city development.

It also features clear socioeconomic gradients, with high-income sectors radiating from the centre and low-income informal settlements forming on the periphery.

Additionally, colonial planning and historical land-tenure patterns exert a stronger, more visible influence in Latin American cities.

The commercial spine concentrates high-end retail, offices, and services, providing a high-amenity corridor connecting the CBD to elite residential areas.

Its importance stems from investment patterns: infrastructure, security, and transport improvements are often prioritised along the spine, reinforcing its centrality.

This creates a development axis that attracts further economic activity and shapes long-term urban expansion.

Informal settlements usually form on marginal land due to limited access to affordable formal housing and weak land regulation.

Common factors include:

Steep hillsides or flood-prone areas that formal developers avoid

Distance from employment centres

Proximity to transport routes, allowing commuting despite peripheral location

Their placement reflects both economic necessity and historical patterns of uneven investment.

Continued rural-to-urban migration sustains demand for low-cost housing, often exceeding the capacity of formal markets.

New migrants frequently settle in existing informal areas due to:

Social networks and community support

Incremental building opportunities

Lower barriers to entry compared with formal neighbourhoods

This cycle helps explain why informal peripheries expand even as cities attempt upgrading projects.

Redevelopment has intensified land values in central areas, sometimes pushing low-income residents outward and reinforcing peripheral inequality.

Some cities have introduced new commercial clusters outside the traditional spine, creating polycentric patterns.

However, despite such changes, the core logic of a dominant CBD, elite corridors, and peripheral informality often remains recognisable across the region.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the structure of the Latin American city model reflects historical patterns of colonial development.

Question 1

1 mark: Identifies a relevant aspect of colonial influence (e.g., centralised planning around a plaza, strong administrative core).

1–2 marks: Explains how this aspect shaped the city’s spatial structure (e.g., centralisation leading to a dominant CBD).

1 mark: Links colonial historical development to a feature of the modern model (e.g., elite residential sector extending from the historic centre).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using the Latin American city model, analyse how socioeconomic inequality is expressed spatially within many Latin American cities. Refer to at least two different zones in your answer.

Question 2

1 mark: Identifies socioeconomic inequality as a key feature of spatial organisation.

1–2 marks: Describes characteristics of at least two zones (e.g., elite residential sector, zone of maturity, peripheral informal settlements).

1–2 marks: Analyses how these characteristics demonstrate inequality (e.g., differences in infrastructure, access to services, housing quality).

1 mark: Provides a clear, geographically informed explanation linking spatial patterns to broader urban processes such as migration or investment patterns.