AP Syllabus focus:

‘Qualitative and quantitative data help show the causes and effects of geographic change within urban areas.’

Urban geographers use data to understand how cities change, why spatial patterns form, and how people experience urban environments. Data reveals relationships, trends, and impacts shaping urban life.

Why Data Matters in Urban Geography

Urban geography examines how people, places, and built environments interact within cities. Because cities constantly evolve, geographers rely on systematic data collection and analysis to identify patterns, diagnose problems, and support evidence-based planning. Without data, understanding complex urban change would be limited to assumptions or isolated observations.

Types of Data and Their Purposes

Urban geographers use two major categories of data—quantitative and qualitative—each contributing different insights into the causes and effects of urban change. These data sources reveal how population shifts, land-use decisions, economic conditions, and community experiences shape cities.

Quantitative Data: Measuring Urban Patterns

Quantitative data includes numerical information that captures measurable dimensions of urban life. Urban geographers use quantitative data to identify scale, frequency, distribution, and change over time.

Quantitative Data: Numerical information used to measure characteristics such as population, income, density, and housing supply.

Quantitative datasets help geographers identify large-scale patterns that might otherwise be invisible.

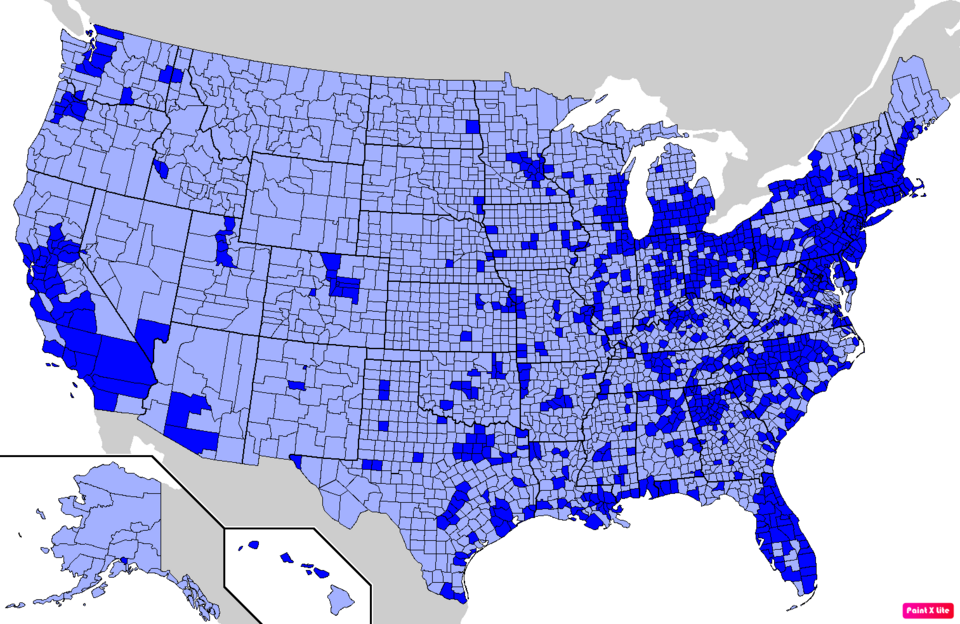

A choropleth map of U.S. counties shaded by population density based on U.S. Census Bureau data. Darker areas indicate denser counties likely reflecting major metropolitan regions. The map includes rural areas beyond the syllabus focus, but it clearly demonstrates how quantitative data visualizations reveal spatial patterns. Source.

For example, shifts in census populations can reveal suburbanization, gentrification, or decline.

Bullet-point uses of quantitative data include:

Measuring population growth, migration flows, and demographic change

Mapping density patterns, land use, or service distribution

Tracking economic indicators such as employment, housing prices, or income levels

Comparing cities or neighborhoods using standardized metrics

Because these data can be statistically analyzed, they allow geographers to detect correlations and trends that help explain urban dynamics.

Qualitative Data: Understanding Human Experiences

Qualitative data includes non-numerical evidence reflecting people’s perceptions, behaviors, and lived experiences.

Qualitative Data: Descriptive information capturing attitudes, behaviors, narratives, and observations within urban environments.

Qualitative data humanizes the study of cities, revealing how individuals experience change such as redevelopment, segregation, or displacement. It helps geographers interpret how policies and economic shifts affect real communities.

Common qualitative methods include:

Interviews with residents, business owners, or planners

Field observations documenting visible environmental and social changes

Narratives or oral histories describing community identity or transformation

Photographs, drawings, or videos that illustrate spatial and cultural patterns

These sources provide depth that complements numerical trends.

Linking Causes and Effects of Urban Change

Urban geographers use data not only to identify what is happening but also to determine why it is happening and what outcomes result. Understanding the causal relationships behind urban change is a central purpose of data collection.

Identifying Causes of Urban Change

Geographers use data to assess why certain patterns emerge, such as:

Economic shifts, revealed by employment and income data

Migration patterns, identified through demographic statistics and interviews

Policy decisions, reflected in zoning records, land-use maps, or development documents

Social factors, captured through surveys and personal narratives

Without systematic data, the drivers behind urban transformations would remain unclear.

Assessing Effects on Urban Space and Society

Data also allows urban geographers to evaluate the consequences of urban change. This includes analyzing how shifts in population, transportation, or land use affect residents and neighborhoods.

Examples of effects measured through data include:

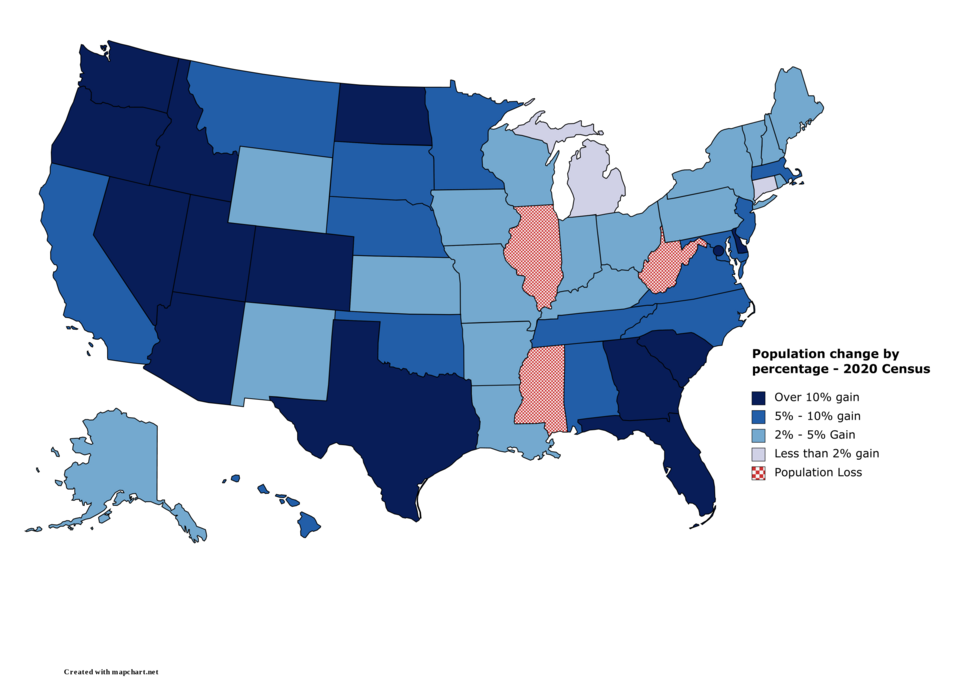

A map of the United States showing population change by state based on 2020 Census data. Color shading indicates where populations have grown or declined, mirroring how quantitative data reveals regional demographic shifts. The image covers state-level trends that include both urban and rural components. Source.

Changing housing affordability and displacement pressures

Altered transportation patterns and commuting distances

Shifts in access to services, such as schools or health care

Emerging environmental impacts, including pollution or land degradation

Redistribution of economic opportunities, mapped through job data

These effects can vary significantly across neighborhoods, making detailed data essential for understanding inequities.

Data Collection Methods in Urban Geography

Urban geographers employ a wide range of tools to gather accurate and meaningful data.

Primary Data Collection

Primary data is collected directly by geographers. It includes:

Field studies documenting building conditions, street activity, and land use

Surveys and questionnaires gathering attitudes or behavioral information

Interviews with residents and local officials

GPS or mobile-based tracking to study movement patterns

A field setup on a highway bridge used to measure traffic volume during a nationwide traffic count. This illustrates how researchers directly collect primary quantitative data on movement and congestion. The image is from a German Autobahn context, which extends beyond the syllabus but clearly depicts a standard data-gathering method. Source.

These methods capture current, ground-level conditions.

Secondary Data Sources

Secondary data comes from existing records and large institutions. Examples include:

National census datasets and population estimates

Government databases on housing, crime, transportation, and economics

Remote-sensing imagery and GIS layers

Academic studies, reports, and archival documents

Secondary data offers long-term, standardized, and large-scale metrics valuable for comparing cities or tracking change over decades.

Why Both Data Types Are Needed

Because cities are both physical and social environments, geographers combine quantitative and qualitative data to build a complete picture. Numerical trends show broad patterns, while descriptive information explains human experiences behind those patterns. Together, these data types allow urban geographers to analyze causes, effects, and meanings of urban change with depth and accuracy.

FAQ

Choice of data depends on what aspect of urban change is being investigated. Quantitative data is selected when the goal is to measure scale, frequency, or distribution, whereas qualitative data is chosen to understand experiences, motivations, or social meaning.

Many studies use both: quantitative data identifies where change is occurring, and qualitative data helps explain why that change matters to communities.

Urban environments can shift rapidly, meaning data collected one month may not reflect conditions the next.

Challenges include:

Limited time to capture accurate snapshots

Difficulty accessing private or restricted areas

Safety concerns in certain neighbourhoods

Rapid redevelopment altering the physical landscape mid-study

Researchers often return repeatedly or combine methods to maintain accuracy.

Mixed-method approaches allow geographers to integrate the strengths of both data types, creating a fuller picture of urban dynamics.

Quantitative data highlights trends such as rising density or demographic shifts, while qualitative perspectives add emotional, cultural, and behavioural insight. This combination helps interpret not only where change happens, but how people experience and respond to it.

Researchers use structured protocols to reduce bias and ensure consistency.

Common strategies include:

Using the same set of questions for each interview

Cross-checking observations with multiple researchers

Recording field notes immediately to prevent memory distortion

Verifying claims with supporting quantitative data when possible

Triangulation strengthens reliability by confirming findings through multiple sources.

Ethical practice requires protecting participant privacy and avoiding harm.

Key considerations include:

Obtaining informed consent for interviews and observations

Ensuring anonymity when discussing sensitive topics such as displacement or income

Avoiding exploitation of vulnerable groups by presenting findings responsibly

Being transparent about how data will be used and who may access it

Ethical research maintains trust and safeguards the dignity of affected communities.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why urban geographers use qualitative data when studying urban change.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark for identifying a valid reason (e.g., captures lived experiences, reveals perceptions, provides context behind numerical trends).

1 additional mark for explaining how qualitative data contributes insight (e.g., shows how residents feel about redevelopment, displacement, or neighbourhood identity).

1 additional mark for linking the explanation to understanding urban change (e.g., helps reveal the social impact of planning decisions or demographic shifts).

Total: 3 marks

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using examples, analyse how quantitative data can help urban geographers identify both the causes and effects of demographic change within a metropolitan area.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

1 mark for identifying a relevant type of quantitative data (e.g., census data, housing price figures, population density statistics).

1 mark for correctly explaining how it identifies a cause of demographic change (e.g., job growth attracting migrants, rising housing costs pushing residents away).

1 mark for correctly explaining how it identifies an effect of demographic change (e.g., shifts in service demand, increased congestion, school capacity changes).

1 mark for providing a clear, appropriate example (e.g., population growth in metropolitan suburbs or decline in inner-city districts).

Up to 2 additional marks for depth of analysis or linking multiple data types to both causes and effects in a coherent manner.

Total: 6 marks