AP Syllabus focus:

‘Census and survey data provide quantitative information about changes in population size and composition in urban areas.’

Urban geographers rely on quantitative data to measure how and why cities change over time, and census and survey data form the backbone of these empirical investigations.

The Role of Quantitative Data in Urban Geography

Quantitative data refers to numerical information that can be measured, compared, and analyzed statistically to understand spatial patterns. Census counts and survey datasets are essential because they allow researchers to identify population change, demographic composition, and spatial variations across different parts of a city. These data sources help urban geographers track processes such as migration, suburbanization, densification, and decline, all of which shape how cities evolve and function.

Census Data: Structure, Strengths, and Geographic Uses

Census data is one of the most authoritative sources of demographic information. It provides standardized population counts at multiple spatial scales that can be used to examine both citywide trends and neighborhood-level changes.

What Census Data Includes

Censuses typically gather information on:

Population size and population distribution

Age, sex, and household structure

Race, ethnicity, and language

Housing characteristics, including occupancy, tenure, and dwelling type

Economic indicators such as income and employment

These categories allow geographers to analyze the composition of urban populations and to see how different characteristics cluster or disperse in urban space.

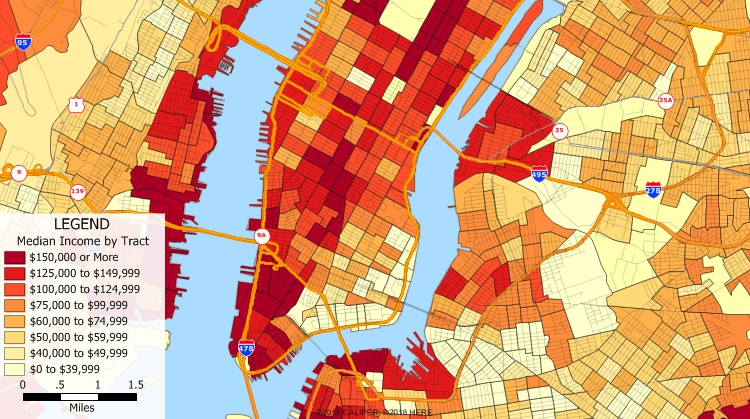

This map displays census tracts in New York City, each shaded according to income data derived from the census. The image demonstrates how census tracts serve as small, relatively homogeneous units that allow urban geographers to map and compare demographic characteristics across a metropolitan area. The inclusion of specific income categories and the New York City example adds detail beyond the syllabus but illustrates the same principles of census-based spatial analysis. Source.

Why Census Data Matters for Urban Studies

Census information is powerful because it is:

Regularly collected, providing consistent benchmarks over decades

Comprehensive, covering all households in a country

Spatially detailed, enabling comparisons among neighborhoods, census tracts, or metropolitan regions

Standardized, meaning categories and definitions remain relatively stable over time

These qualities make the census indispensable for tracking long-term urban growth, identifying segregation patterns, and understanding housing pressures.

Key Terms Introduced in Census Analysis

When census data is first used in urban studies, several foundational concepts become essential for interpreting results.

Population Density: The number of people per unit of land area, used to compare how tightly or sparsely people are distributed within an urban space.

High-density tracts may indicate central-city environments, while low-density tracts often reflect suburban or peripheral zones.

Survey Data: Flexibility and Fine-Grained Insights

While census data provides broad, periodic benchmarks, survey data allows urban geographers to capture more detailed and more frequent information. Surveys may be conducted by national governments, research organizations, metropolitan planning agencies, or academic institutions.

What Survey Data Provides

Surveys often include:

Household income and expenditures

Travel behavior and commuting patterns

Housing preferences, tenure changes, and mobility intentions

Perceptions of neighborhood quality

Educational attainment

Migration histories

Because survey questions can be tailored, geographers use them to explore variables that the census does not capture in detail.

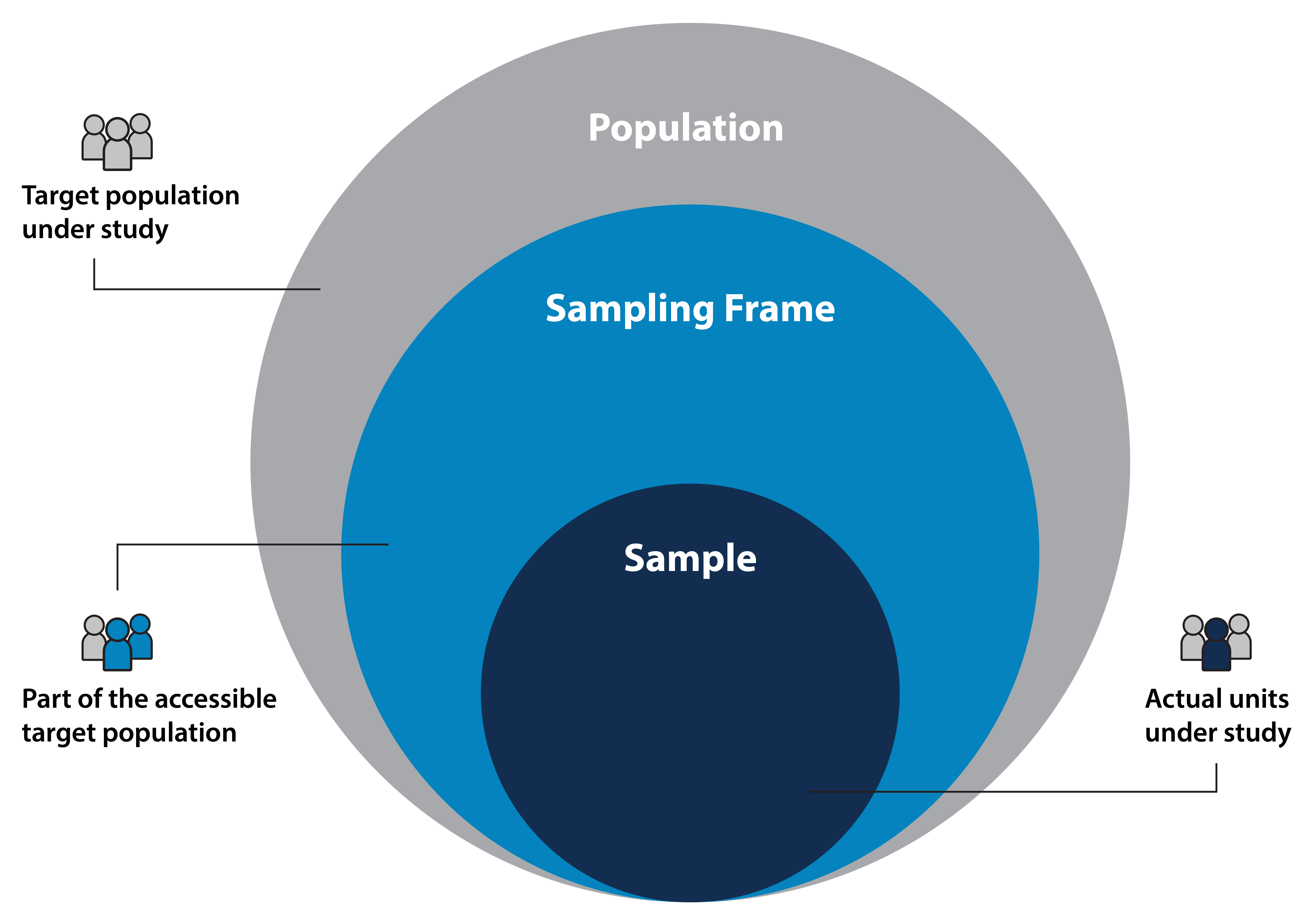

This diagram illustrates the relationship between the total population, the accessible sampling frame, and the smaller sample actually studied in a survey. It reinforces how survey-based quantitative data comes from a subset of individuals, which must be carefully chosen to represent the broader urban population. The health-statistics context of the original source adds minor extra detail, but the population–sample logic is identical for urban geographic surveys. Source.

Strengths of Survey-Based Quantitative Data

Survey data is especially useful because it can:

Target specific subpopulations, such as recent migrants or renters

Track short-term changes, unlike the census’s long intervals

Provide attitudinal or behavioral information that supports deeper explanations of urban processes

Fill knowledge gaps in rapidly changing neighborhoods

These features allow geographers to understand not just where change is occurring, but why.

Integrating Census and Survey Data in Urban Analysis

Urban geographers rarely rely on one type of quantitative data alone. Instead, they combine census and survey sources to paint a more complete picture of urban change.

How These Sources Work Together

Census data identifies broad patterns of growth or decline.

Surveys help determine the human motivations behind those patterns.

Census maps reveal spatial clustering of demographic groups.

Surveys explain behavioral factors influencing settlement choices.

Census counts measure population shifts.

Surveys reveal drivers of mobility, such as job changes or housing costs.

Using both allows geographers to analyze:

Segregation and integration

Gentrification pressures

Commuting flows

Housing market stress

Changing age structures

These urban dynamics cannot be fully understood without numerical measurements from both sources.

Data Accuracy, Limitations, and Considerations

Census and survey data are powerful, but urban geographers must understand their limitations to interpret results accurately.

Accuracy Considerations

Undercounting can occur, especially among marginalized populations, renters, or people experiencing homelessness.

Sampling errors may emerge in surveys because they rely on smaller population subsets.

Category limitations may mask complex identities or demographic nuances.

Temporal gaps in census cycles can obscure rapid changes between counts.

Sampling Error: A difference between survey results and the true population value that arises because only part of the population is surveyed.

Understanding limitations helps geographers decide when to use large-scale census data and when more flexible survey data is required.

How Geographers Apply These Data Sources

Quantitative data enables geographers to measure urban change and evaluate policy outcomes.

Common Applications

Mapping population change across census tracts

Measuring migration flows and mobility

Assessing housing affordability trends

Identifying transportation needs

Evaluating environmental justice patterns

Monitoring neighborhood demographic shifts over time

These applications illustrate why census and survey data are central to studying urban development, inequality, and spatial transformation.

FAQ

Census categories are often reviewed every cycle, but changes occur slowly to maintain comparability over time. Adjustments may reflect evolving social identities, new migration patterns, or shifts in household structures.

These changes matter because even small definitional updates can affect long-term trends, making it harder to compare urban demographic data across decades. Analysts must therefore note when categories shift to avoid misinterpreting changes that stem from definitions rather than real population movement.

Census microdata provides anonymised individual or household responses, allowing finer-grained analysis than standard tables.

It can reveal:

Variations in mobility patterns within the same census tract

Differences between household types that aggregate categories might obscure

More precise relationships between variables such as income, tenure, and age

Microdata allows urban geographers to explore internal differences that broad tract-level summaries can flatten.

Urban residents experience diverse socioeconomic conditions, which can influence willingness or ability to respond accurately. Groups such as recent migrants, low-income households, or those with limited digital access may be underrepresented.

This bias affects data quality by skewing survey results toward more stable or accessible populations. As a result, planners may underestimate needs in marginalised areas or draw incorrect conclusions about urban social change.

Small-area census data identifies where people live and the demographic characteristics of those areas. Transport surveys reveal how people travel, including route choice, journey purpose, and timing.

Together they allow geographers to:

Map demand for different transport modes

Detect mismatches between housing locations and job centres

Identify areas where commuting burdens fall disproportionately on certain groups

This integration supports more equitable and efficient transport planning.

Informal settlements often lack official addresses, making enumeration difficult. Residents may also be reluctant to participate due to legal or social vulnerabilities.

These challenges lead to undercounting, inconsistent boundaries, and gaps in household information. Survey teams may struggle with access, and census workers may not update maps quickly enough to reflect growth.

As a result, population size, density, and demographic characteristics may be significantly underestimated, affecting resource allocation and policy decisions.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why census data is valuable for studying patterns of population change within a city.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid reason (e.g., census data provides comprehensive population counts).

1 mark for explaining how this reason supports urban analysis (e.g., enables comparison across different neighbourhoods).

1 mark for linking to population change (e.g., tracks increases or decreases in specific areas over time).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Discuss how survey data can complement census data in understanding urban demographic and social change. Refer to two different ways in which survey data adds value.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying first way survey data complements census data (e.g., captures detailed behavioural or attitudinal information).

1 mark for explaining this way.

1 mark for identifying a second way (e.g., provides more frequent updates than a decennial census).

1 mark for explaining this way.

Up to 2 additional marks for clear discussion of how the two data sources together improve overall understanding of urban change (e.g., linking motivations to spatial patterns, clarifying reasons behind migration or housing decisions).