AP Syllabus focus:

‘Quantitative data can reveal patterns such as segregation, growth, decline, and shifting density when mapped and compared across time.’

Urban geographers analyze quantitative patterns to understand how cities evolve, identifying measurable shifts in population, land use, and spatial organization that reveal deeper social, economic, and demographic processes.

Identifying Patterns Through Quantitative Urban Data

Quantitative patterns help geographers interpret measurable urban changes, emphasizing how cities grow, decline, or restructure over time. These patterns often emerge when data are mapped, graphed, or compared longitudinally. By examining trends rather than isolated numbers, geographers can identify structural transformations and make evidence-based interpretations about the forces shaping urban spaces.

The Importance of Spatial Patterns

A core function of quantitative urban analysis is evaluating spatial distribution, meaning how people and activities are arranged across the landscape. Spatial patterns allow geographers to distinguish between localized changes and citywide trends. Quantitative data reveal whether certain neighborhoods concentrate particular social groups, experience population turnover, or undergo cyclical reinvestment or disinvestment. These patterns provide clues about the broader processes driving urban change, such as suburbanization, deindustrialization, or gentrification.

Revealing Segregation Patterns

Segregation, the spatial separation of groups based on characteristics such as race, ethnicity, or income, is one of the clearest patterns detectable through quantitative analysis.

Segregation: The spatial separation of groups within an urban area based on demographic or socioeconomic characteristics.

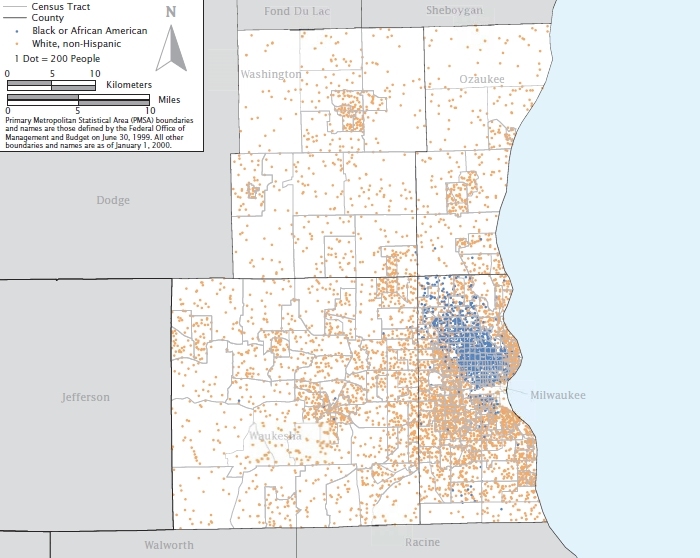

Segregation patterns often emerge in quantitative maps showing where different groups live. Measurements such as the dissimilarity index or distributional ratios highlight unevenness between neighborhoods. These patterns help geographers identify how historical policies, housing markets, and transportation networks have shaped the separation of groups across the city. Even without advanced statistical tools, simple measures such as census tract compositions reveal stark divides that may remain consistent or shift slowly across decades. Such patterns allow researchers to track whether segregation is intensifying, declining, or changing form.

Quantitative segregation patterns also illuminate how access to services and opportunities varies across space. Areas with concentrated disadvantage often overlap with low investment, higher pollution exposure, and limited infrastructure, demonstrating how measurable spatial patterns translate into lived outcomes.

This map shows levels of Black residential segregation in Milwaukee based on 2000 Census data, with darker shades indicating stronger segregation patterns. It illustrates how segregation concentrates in specific neighborhoods, shaping unequal access to opportunities. The image is more location-specific than the AP syllabus requires but effectively demonstrates how segregation patterns appear in quantitative mapping. Source.

Revealing Growth Patterns

Urban growth is another key pattern detected through quantitative data. Population counts and density measures reveal where cities are gaining residents, where new housing is built, and how economic development influences settlement.

Growth: An increase in population, development, or economic activity within an urban area or specific neighborhood.

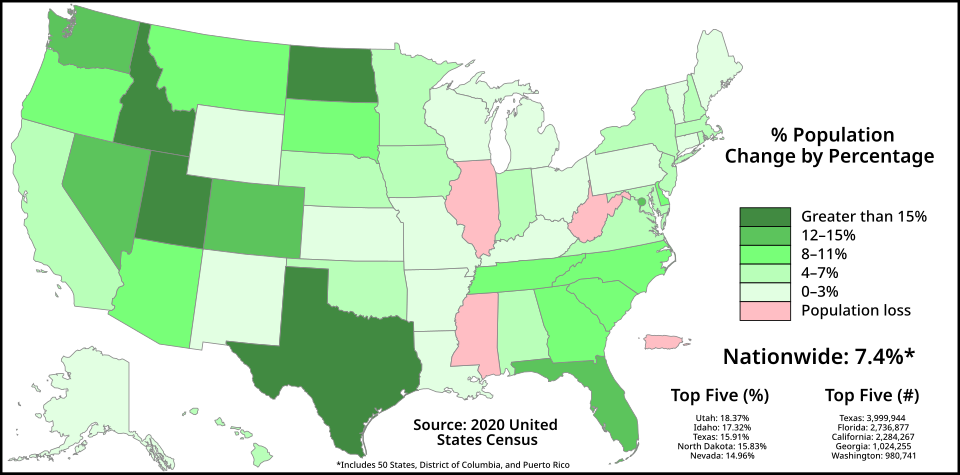

Mapping population change across multiple census periods highlights which neighborhoods are expanding. Some areas experience rapid residential development, especially in suburban zones shaped by new transportation links or availability of land. High growth areas often correspond with employment centers, amenities, or local policy incentives encouraging development.

Growth patterns help identify the speed and direction of urban expansion. For example, outward growth indicates suburbanization, whereas upward growth—measured through increasing density—signals redevelopment or infill. This information helps geographers understand the long-term pressures placed on infrastructure, transportation, and housing markets.

This map displays population change across U.S. states using 2020 Census data, with colors showing which states gained or lost residents. It provides a clear geographic overview of regional growth and decline patterns. The state-level scale includes more regional detail than required for AP Human Geography, but it effectively demonstrates how quantitative growth and decline patterns appear on maps. Source.

Revealing Decline Patterns

Quantitative data can also reveal decline, a reduction in population or economic activity that reshapes urban landscapes.

Decline: A measurable decrease in population, investment, or economic vitality within a city or specific neighborhood.

Decline patterns emerge through falling population numbers, increased vacancy rates, or reductions in property values. These patterns often map onto former industrial zones or aging suburbs where reinvestment lags behind contemporary economic shifts. Quantitative indicators highlight where shrinkage is concentrated, helping geographers link observable decline to structural causes such as job loss, suburban flight, or housing obsolescence. Recognizing declining areas is important for identifying zones of abandonment and understanding uneven development.

A neighborhood’s decline may occur simultaneously with growth elsewhere, revealing how urban restructuring redistributes people and resources across the metropolitan area.

Revealing Shifting Density

Density—how many people occupy a given area—provides insight into how residents distribute themselves within the city. Shifting density patterns help geographers understand how land use evolves under changing demographic and economic pressures.

Density: The number of people or units per unit of land area, often measured as persons per square mile or kilometer.

Shifts in density may reflect infill development, changes in housing types, or population turnover. Increasing density often indicates redevelopment, especially in central neighborhoods undergoing revitalization. Decreasing density signals disinvestment or suburban sprawl as households spread across larger areas. When compared across time, density maps reveal how transportation improvements, zoning policies, and economic priorities influence where people live and how compact or dispersed urban form becomes.

Understanding density changes also helps identify pressures on infrastructure, housing availability, and the overall spatial footprint of the city.

The Value of Longitudinal and Comparative Mapping

Quantitative patterns become clearest when data are compared over time or across neighborhoods. Longitudinal mapping shows how spatial patterns evolve, while cross-sectional comparisons reveal disparities between areas. These analytical approaches allow geographers to interpret urban transformation as a dynamic process rather than a static snapshot. Such comparisons clarify trends such as suburban expansion, central-city revitalization, deindustrialization, gentrification, environmental inequality, and demographic shifts.

FAQ

Geographers choose indicators based on the specific pattern they want to understand. For segregation, they may rely on demographic distributions; for growth or decline, they prioritise population change or housing data.

Indicator selection also depends on spatial scale. Some measures work best at the neighbourhood level, while others reveal clearer trends at the regional or metropolitan scale.

Choropleth maps are widely used because they allow quick visual comparison of values across space. However, they may obscure variation within large units.

Dot density maps are useful for showing the actual distribution of people or features, which helps identify clustering.

Heat maps highlight intensity and gradual change, making them effective for displaying shifting density or gradual population gradients.

Single-year data may hide ongoing processes such as slow decline or early redevelopment. Comparing multiple time points allows geographers to see whether a trend is emerging, stabilising, or reversing.

Longitudinal comparisons also reveal whether changes are cyclical or structural, helping distinguish between short-term fluctuations and long-term transformation.

Natural change is reflected in birth and death rates, which tend to shift gradually across space.

Migration-driven change produces more spatially uneven patterns, such as sudden population increases in one area and corresponding declines elsewhere.

By layering multiple datasets—population counts, age structure, and migration statistics—geographers can identify which process is playing the dominant role in shaping urban patterns.

Quantitative maps and statistics can oversimplify urban processes if the spatial units used are too large, masking internal variation. This is known as the modifiable areal unit problem.

Patterns may also reflect historical boundaries or administrative decisions rather than real social or economic divisions.

Without qualitative context, data might suggest change where none exists, or hide emerging issues that have not yet appeared in measurable indicators.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Using quantitative urban data, identify two types of spatial patterns that geographers can reveal when analysing changes within a city. Briefly explain how each pattern contributes to understanding urban processes.

Question 1

Award up to 3 marks:

• 1 mark for identifying each pattern (maximum 2 patterns).

• 1 additional mark for a valid explanation of either or both patterns (maximum 1 mark).

Acceptable patterns include: segregation, growth, decline, shifting density, spatial clustering, or dispersal.

Explanations may include how segregation reveals uneven access to services, how growth or decline shows changing investment or population shifts, or how density patterns reflect redevelopment or sprawl.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Quantitative data are often mapped or compared over multiple time periods to understand how cities change. Explain how quantitative patterns of segregation, growth or decline, and shifting density can be used to interpret the social and economic restructuring of an urban area. Refer to how geographers use mapped or statistical data to draw conclusions.

Question 2

Award up to 6 marks:

• 1–2 marks for describing how quantitative patterns of segregation appear in mapped or statistical data (e.g., distribution of groups, concentration in particular neighbourhoods).

• 1–2 marks for explaining growth or decline patterns using population counts, census change, or spatial indicators of investment and disinvestment.

• 1–2 marks for explaining how shifting density reveals redevelopment, infill, or suburban sprawl, supported by how geographers interpret density maps or longitudinal data.

Answers should link quantitative patterns to broader urban restructuring processes, such as changing demographics, infrastructure pressures, or variations in access to opportunities.