AP Syllabus focus:

Field studies provide qualitative information by observing places directly and documenting how people experience urban change.

Urban field studies help geographers understand how people experience, interpret, and respond to urban change by collecting on-the-ground observations that reveal lived realities beyond statistics.

Field Studies in Urban Geography

Field studies are a core qualitative method used by urban geographers to gain firsthand insights into spatial behavior, urban environments, and community experiences within cities experiencing change. Unlike remote or numerical data sources, field studies emphasize direct observation, allowing geographers to interpret urban landscapes as they actually function.

Because fieldwork captures the nuances of everyday life, it is crucial for analyzing phenomena such as neighborhood transition, land-use conflicts, environmental hazards, or social inequalities. Field-based data also helps validate or challenge patterns seen in maps, surveys, and census statistics.

What Field Studies Involve

Field studies draw on a range of observational strategies that help geographers understand the textures and complexities of urban places. These methods allow researchers to see how urban change plays out on streets, in public spaces, and across neighborhoods.

Direct and Systematic Observation

Direct observation involves watching how people interact with the built environment and with each other in real time. Systematic observation adds more structure by using coded categories or mapping routines.

Systematic Observation: A structured method of recording behaviors, land uses, or conditions in a consistent, replicable way across study sites.

Researchers may document:

Pedestrian movement patterns and crowd behavior

Types of land uses present on each block

Building conditions, signage, or evidence of investment and disinvestment

Accessibility of public transportation or public spaces

Environmental hazards such as noise, pollution, or flooding indicators

These observations can be captured using field notes, photographs, sketch maps, GPS points, or mobile apps.

A single neighborhood may be observed multiple times to capture variations by time of day, weekdays versus weekends, or seasonal changes.

Fieldwork often documents how different land uses—such as shops, housing, transit stops, and vacant lots—are arranged along streets and across neighborhoods.

Main Street in downtown Ames, Iowa, illustrates a mixed-use streetscape that researchers commonly observe during field studies. The image highlights building condition, signage, and pedestrian infrastructure relevant to documenting urban land use. Some historic façade details exceed syllabus expectations but still support understanding of real-world environments. Source.

Environmental and Spatial Assessments

Field studies often include assessments of the urban landscape to better understand how environmental and spatial conditions shape residents’ experiences. These assessments may involve:

Mapping infrastructure quality such as sidewalks, lighting, or transit stops

Identifying land-use conflicts where industrial, commercial, and residential uses meet

Documenting evidence of environmental injustice, including proximity to highways or waste facilities

Assessing the distribution of green space or public amenities

These observations support deeper analysis of equity, access, and livability within urban areas.

Field Studies as Lived Experience Data

Fieldwork is essential for capturing lived experiences, or how individuals and groups perceive and navigate the city around them.

Understanding Experience, Identity, and Place

Field studies allow geographers to see how urban change affects identity, attachment to place, and social dynamics. These insights can reveal:

How residents respond to gentrification or redevelopment

The social importance of gathering spaces such as markets, plazas, parks, or transit hubs

Cultural landscapes shaped by religion, ethnicity, or migration

Emotional geographies, including comfort, exclusion, fear, or belonging

Although quantifiable data may show demographic changes, only fieldwork can illuminate how these changes feel to the people living through them.

Documenting Informal and Unmapped Urban Activity

Cities across the world include activities that are often missing from formal datasets. Field studies help geographers document these invisible or marginal dynamics:

Street vending, informal markets, and food carts

Informal transportation systems

Squatter or informal settlements

Temporary or shifting land uses

Graffiti, murals, and other expressions of cultural identity

These observations offer vital insight into urban economies and social networks that are rarely captured statistically.

Field Studies in Urban Change Analysis

Urban change frequently reshapes neighborhoods unevenly, and field studies help reveal who benefits and who faces burdens. These uneven geographies can be assessed by comparing observed conditions across multiple sites.

Detecting Neighborhood Transitions

Field observations help pinpoint early signs of neighborhood transformation, including:

New construction or renovation

Shifts in commercial activity

Changing demographics visible through consumer goods or linguistic signage

Alterations to local transportation flows

Expanding tourist presence

Because these shifts often appear before census data is updated, field studies provide early indicators of transition.

Linking Field Evidence to Broader Urban Processes

Field studies become even more powerful when connected to larger urban theories or regional patterns. Observations can help explain processes such as:

Gentrification, shown through renovation, amenity growth, or rising commercial turnover

Disinvestment, evident in deteriorating infrastructure or vacant properties

Urban revitalization, marked by new public spaces or infrastructure improvements

Environmental injustice, revealed by the spatial clustering of hazards

These insights help geographers understand how macro-level forces shape micro-level experiences.

Strengths and Limitations of Field Studies

Field studies contribute uniquely rich data, but they also have boundaries. Geographers must remain aware of both advantages and limitations when interpreting their observations.

Strengths

Provide detailed, context-rich insights unavailable in quantitative data

Reveal lived experiences and informal activities

Capture real-time processes of urban change

Allow researchers to interpret spatial behavior directly

Support ground-truthing of maps, models, and statistical patterns

Researchers frequently sketch or annotate maps to capture building uses, environmental conditions, and signs of investment or disinvestment across blocks or entire districts.

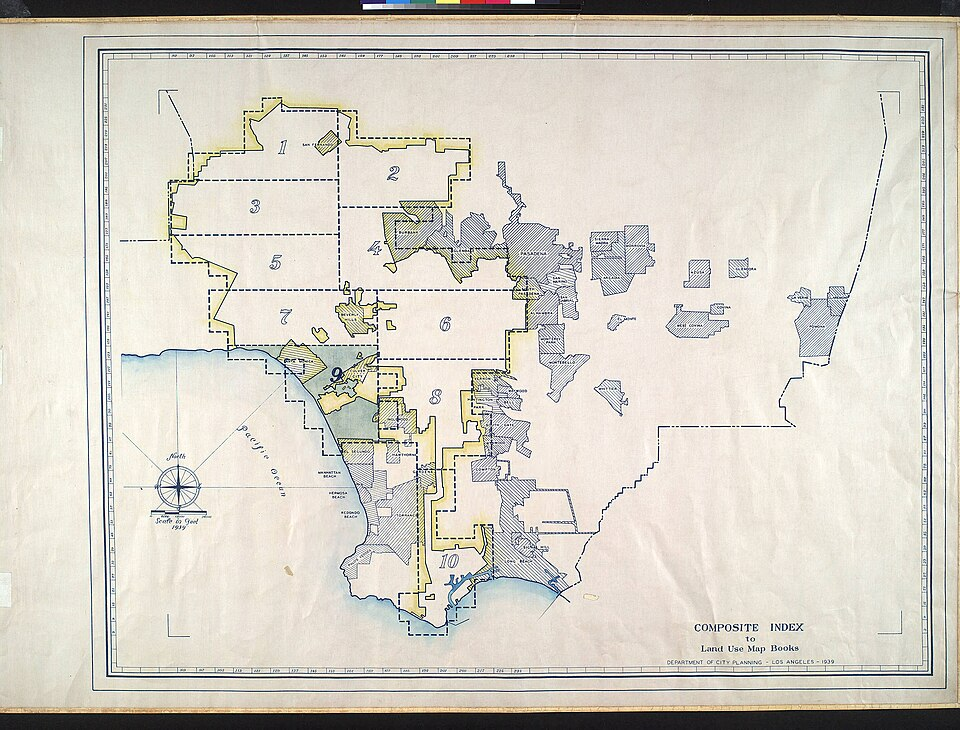

This WPA land-use survey map demonstrates how field observations can be translated into color-coded spatial data. It shows residential, industrial, and commercial zones organized through systematic ground surveys. The detailed legend and historical context exceed AP requirements but illustrate how professional mapping conventions structure field-study data. Source.

Limitations

Observations may be subjective and influenced by researcher bias

Data may not represent all times, groups, or locations

Time-intensive and limited in geographic scale

Harder to generalize compared to large datasets

Mobile apps, GPS, drones, and webcams can supplement in-person observation and create digital records of urban change.

A street mapping vehicle equipped with panoramic cameras captures continuous visual data along urban routes. Such tools complement traditional field notes by documenting façades, signage, and spatial features. Technical camera details extend beyond syllabus needs but clarify how technology supports contemporary field studies. Source.

FAQ

Site selection usually focuses on areas undergoing visible or suspected change, such as zones of redevelopment, declining commercial corridors, or neighbourhoods with recent demographic shifts.

Researchers often use secondary sources first—such as planning documents, local news, or preliminary mapping—to identify potential hotspots.

They also consider:

Accessibility and safety

Representativeness of wider urban processes

Diversity of land uses and social activity

A mix of contrasting sites is often chosen to show spatial variation within the same city.

Common tools include voice memos, short video clips, sketch maps, and structured observation sheets tailored to specific research questions.

In crowded environments, hands-free or streamlined tools work best, such as:

Wrist-mounted or pocket-sized GPS devices

Smartphone apps with coded data entry

Quick annotation templates for noting land use, building condition, or environmental quality

These tools allow the researcher to capture information rapidly without disrupting pedestrian flows.

Researchers typically use systematic protocols that standardise what is recorded, reducing variation caused by personal interpretation.

Approaches include:

Predefined checklists

Agreed coding categories for building use or condition

Conducting observations at multiple times of day

Having more than one researcher observe the same site

Triangulating findings with other qualitative or quantitative sources also helps validate interpretations.

Researchers often schedule repeated visits at different times to document variations in activity patterns, such as street vending, informal transport, or temporary markets.

They may use:

Time-lapse photography

Short timed counts of people or vehicles

Notes on appearance and disappearance of temporary structures

Observing rhythms across the day helps reveal how spaces serve multiple functions beyond their formal land-use category.

Although public spaces typically do not require formal consent, researchers must still act responsibly, avoiding intrusive behaviour and respecting privacy.

Ethical practice includes:

Not photographing individuals in a way that identifies them without permission

Avoiding sensitive sites where observation may cause discomfort

Remaining transparent about research aims if approached by community members

Awareness of local norms and power dynamics ensures that fieldwork does not disadvantage or misrepresent residents.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way field studies provide insights into urban change that quantitative data alone cannot offer.

Question 1

Award up to 3 marks for any of the following, up to a maximum of one mark per bullet unless otherwise stated:

Identifying that field studies capture lived experience, behaviour, or perceptions not visible in numerical datasets (1 mark).

Explaining that fieldwork reveals subtleties such as signs of gentrification, social interaction, or informal activity (1 mark).

Explaining how direct observation can identify early signs of change (e.g., new construction, shifting commercial activity) before statistics are updated (1 mark).

Answers must refer specifically to the value of qualitative field observations.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using examples from urban fieldwork practices, analyse how direct observation and mapping techniques help geographers understand patterns of investment and disinvestment within a city.

(6 marks)

Question 2

Award marks as follows (any valid example acceptable):

Direct Observation (up to 3 marks):

Identifying that direct observation allows geographers to see building conditions, street activity, or land-use changes in real time (1 mark).

Explaining how observing environmental cues such as vacant properties, new amenities, or declining infrastructure indicates investment or disinvestment (1 mark).

Providing an example such as noting boarded-up shops, new cafés, street improvements, or visual evidence of redevelopment (1 mark).

Mapping Techniques (up to 3 marks):

Identifying that geographers sketch or annotate maps to record land uses or environmental conditions (1 mark).

Explaining how mapping allows comparison across blocks or districts to identify spatial clustering (1 mark).

Providing an example such as colour-coding buildings by condition, land-use type, or level of investment (1 mark).

Top-tier answers (5–6 marks) should show clear analysis linking methods to understanding spatial unevenness in urban change.