AP Syllabus focus:

‘Exploration of the key principles that define a well-designed experiment, including comparisons, random assignment of treatments, replication, and control of potential confounding variables. The role of each principle in enhancing the reliability and validity of experimental results will be highlighted.’

Principles of Well-Designed Experiments

A well-designed experiment is built on foundational principles that ensure trustworthy evidence of cause-and-effect. These principles enhance reliability, reduce bias, and strengthen the validity of conclusions.

Introduction

Effective experimental design relies on structured comparisons, proper use of randomness, and repeated observations to ensure that treatment effects can be distinguished from natural variability or confounding influences.

The Purpose of Well-Designed Experiments

A well-designed experiment aims to isolate the impact of an explanatory variable on a response variable while controlling external influences. This structure helps researchers determine whether a treatment truly causes observed changes. Each principle—comparison, random assignment, replication, and control of confounding variables—contributes to achieving this goal in complementary ways.

Principle 1: Comparison

Comparison is the foundation of experimental reasoning because it allows researchers to evaluate differences across conditions rather than interpreting outcomes in isolation.

Why Comparison Matters

An experiment without comparison cannot determine whether a treatment produces an effect beyond what might occur naturally. Comparison creates a meaningful baseline.

Types of Comparison

Treatment group vs. control group

Multiple treatment levels

Placebo conditions when appropriate

Alternative treatment comparisons for evaluating relative effectiveness

Principle 2: Random Assignment

Random assignment is the process of using chance to assign experimental units to treatments.

Random Assignment: The use of chance-based methods to distribute subjects across treatment groups so that all groups are expected to be similar before treatment is applied.

Random assignment equalizes groups with respect to both known and unknown variables by balancing natural variation. This balance allows any differences in outcomes to be attributed more confidently to the treatment rather than preexisting differences.

Methods of Random Assignment

Random number generators to assign subjects

Randomized lists or shuffled groupings

Drawing lots, slips, or other fair chance mechanisms

Why Random Assignment Enhances Validity

Reduces systematic differences between groups

Minimizes confounding

Establishes the basis for causal inference, a central purpose of experimentation

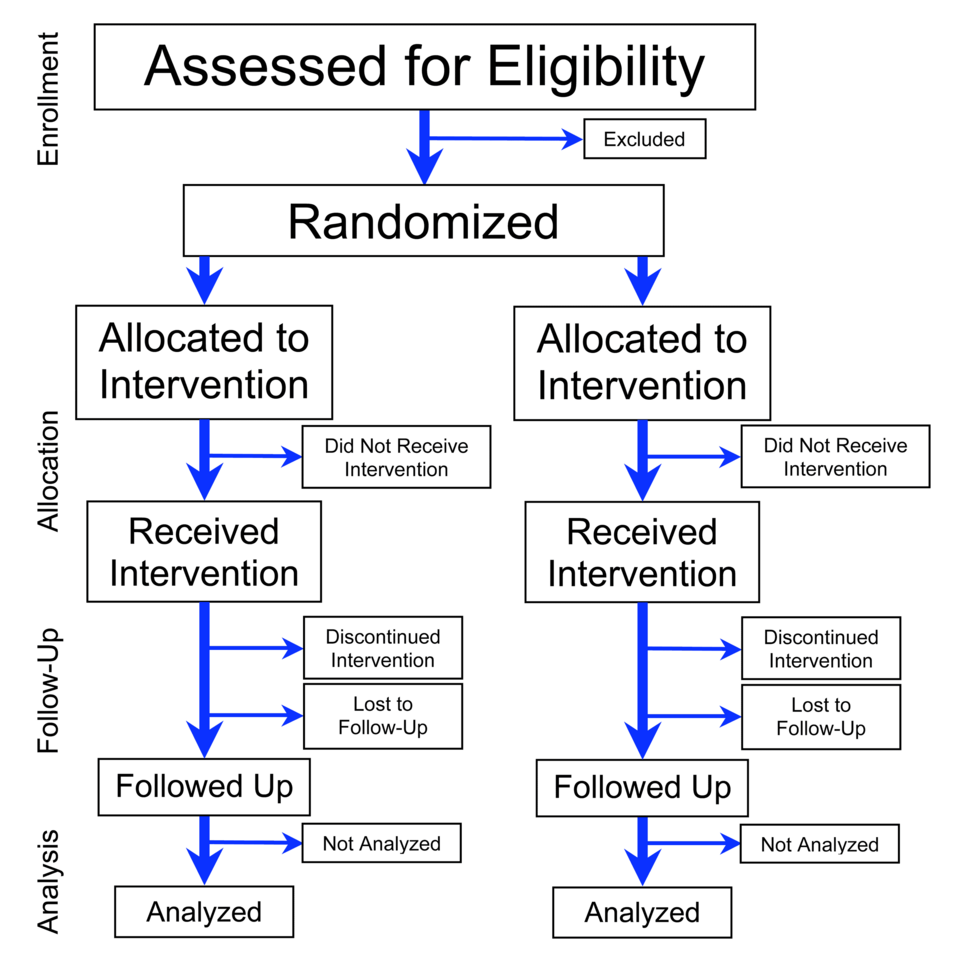

A flowchart depicting the structure of a randomized controlled trial, illustrating how random assignment and parallel treatment groups support causal inference by balancing variation across groups. Source.

Principle 3: Replication

Replication refers to applying each treatment to enough experimental units to obtain stable and reliable outcomes.

Replication: The use of sufficiently large numbers of experimental units to ensure that treatment effects can be distinguished from random variation.

Replication strengthens statistical reliability by reducing noise in the response variable. Adequate replication enables clearer distinctions between treatment effects and natural fluctuations.

How Replication Improves Reliability

Produces more precise estimates of treatment effects

Reduces the influence of outliers or extreme responses

Supports stronger generalization within the experiment’s context

Principle 4: Control of Confounding Variables

Confounding variables are factors associated with both the explanatory variable and the response variable, making it difficult to determine whether the treatment or some unrelated factor caused the outcome.

Confounding Variable: A variable that is related to both the explanatory variable and the response variable, potentially distorting the observed relationship between them.

Controlling confounding variables protects the clarity of treatment effects by holding potentially influential factors consistent across treatment groups.

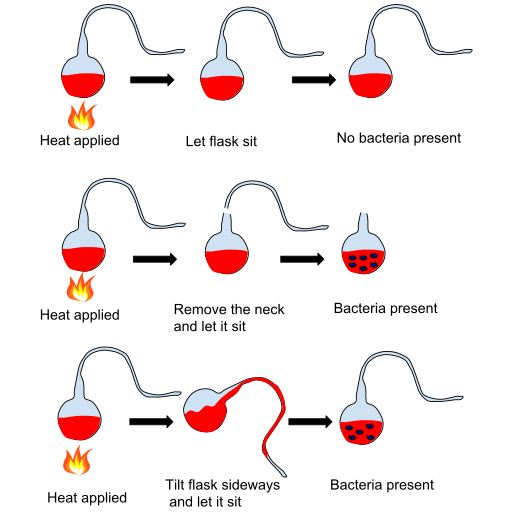

Louis Pasteur’s swan-neck flask diagram demonstrating control of confounding variables by holding conditions constant except for exposure to airborne particles, illustrating how controlled setups isolate explanatory variables. Source.

Strategies for Controlling Confounding

Holding variables constant across all groups

Standardizing procedures, such as timing, instructions, or environment

Using control groups to establish baseline behavior

Implementing blinding to reduce expectation effects

Normal text here ensures appropriate spacing between definition blocks and continues building the conceptual framework for controlling confounding influences.

Integrating the Principles

Well-designed experiments use all four principles together. Their integration creates a structure where differences in outcomes can be attributed to treatments with confidence.

Combined Effects of the Principles

Comparison ensures measurable differences can be observed.

Random assignment makes those differences interpretable as causal rather than accidental or systematic.

Replication provides enough evidence to distinguish signal from noise.

Control of confounding variables ensures the observed effect is not influenced by other factors.

Practical Considerations When Applying the Principles

Researchers must consider practical limitations while ensuring adherence to design principles. Key considerations include:

Ensuring Comparability

Avoid unequal group sizes when possible

Maintain consistent conditions during data collection

Strengthening Random Assignment

Use transparent, documented methods

Avoid convenience-based assignment that risks hidden bias

Applying Adequate Replication

Estimate the sample size needed to see meaningful differences

Recognize that too few units can undermine inference

Improving Control

Use procedural checklists to maintain consistency

Consider blinding to reduce subconscious influences

Why These Principles Matter for AP Statistics

Understanding these principles equips students to interpret data from experiments accurately and evaluate whether causation claims are justified. These concepts form the backbone of experimental reasoning and inform later topics such as inference and significance testing.

FAQ

Random assignment determines which treatment each experimental unit receives, ensuring groups are comparable before the treatment is applied.

Random sampling is a method of selecting individuals from a population for inclusion in a study. It affects how widely results can be generalised, not whether causal conclusions can be drawn.

In experiments, random assignment is essential for establishing causality, whereas random sampling is desirable but not required for strong internal validity.

Some experiments use multiple treatment groups rather than a traditional control group when all conditions involve an active intervention.

A control group may be unnecessary when:

• The goal is to compare different levels or types of treatment.

• A baseline response is already well established in prior research.

• Withholding a treatment would be unethical.

The key requirement is the presence of meaningful comparison, not the presence of an untreated group.

Replication is determined by balancing statistical precision with practical constraints such as time, cost, and availability of subjects.

Researchers may consider:

• Expected variability in the response variable

• The minimum detectable effect size

• Whether results must apply to diverse units or a narrow group

Power analyses, although not required knowledge for AP Statistics, are often used in real research to estimate suitable sample sizes.

Confounding can be reduced but not always eliminated, especially in studies involving complex biological, social, or environmental systems.

Researchers use strategies such as:

• Random assignment

• Standardisation of procedures

• Restricting the study population

• Blinding where feasible

Even with careful design, unmeasured confounders may remain, but well-designed experiments minimise their influence enough to support causal interpretation.

Comparison reveals whether outcomes differ across conditions, enabling meaningful interpretation of treatment effects.

Without comparison:

• There is no benchmark to judge whether an observed result is unusual.

• Natural variability cannot be distinguished from treatment effects.

• Causal reasoning becomes impossible.

Comparison allows patterns to emerge clearly and supports the entire structure of experimental logic.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A researcher wants to test whether a new revision technique improves students’ test performance. She randomly assigns half of the students to use the new technique, while the other half continue with their usual study method. Explain why random assignment is essential in this experiment.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark: States that random assignment distributes students by chance or avoids systematic differences between groups.

1 mark: Explains that it reduces or controls confounding variables.

1 mark: Explains that it allows differences in performance to be attributed to the revision technique rather than pre-existing differences.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A scientist is investigating whether a new fertiliser increases the height of tomato plants. She grows 40 plants in identical conditions. Twenty plants are randomly assigned to receive the new fertiliser, and the remaining twenty receive no fertiliser.

(a) Identify and describe two principles of a well-designed experiment that are evident in this study.

(b) State one potential confounding variable the scientist should control and explain why it is important to control it.

(c) Explain how replication strengthens the conclusions drawn from this experiment.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(a) (Up to 3 marks)

1 mark: Identifies comparison (treatment vs control groups).

1 mark: Describes that comparison allows differences in plant height to be attributed to the fertiliser.

1 mark: Identifies random assignment and explains that it helps create similar groups before treatment.

(b) (Up to 2 marks)

1 mark: States a plausible confounding variable (for example: sunlight, soil quality, pot size, watering amount).

1 mark: Explains why it must be controlled to ensure observed differences are due to the fertiliser alone.

(c) (Up to 1 mark)

1 mark: Explains that replication (using many plants) reduces the effect of natural variability and leads to more reliable and generalisable results.