AP Syllabus focus:

‘Introduction to the fundamental components of an experiment, including experimental units (individuals or objects), explanatory variables (factors), treatments (levels or combinations of levels of the explanatory variable), and response variables (outcomes measured after treatment administration). The significance of identifying each component for designing an experiment will be emphasized.’

This section introduces the essential building blocks of experiments, showing how clearly defining each component strengthens experimental design, supports valid comparisons, and enhances the credibility of cause-and-effect conclusions.

Understanding the Components of an Experiment

Experimental studies rely on a structured framework that allows researchers to investigate how specific conditions influence outcomes.

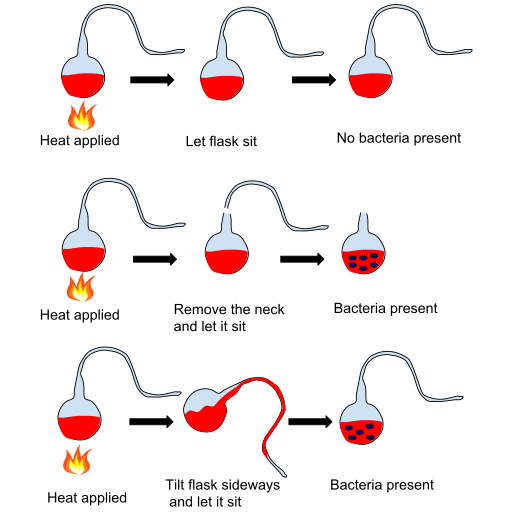

This diagram illustrates an experiment using flasks as experimental units, heat and flask-neck conditions as treatments, and bacterial growth as the measured response. The visual sequence highlights how altering treatment conditions produces different outcomes. The additional biological context extends beyond the syllabus but helps ground the components of an experiment in a real scientific setting. Source.

In AP Statistics, four primary components form the foundation of this framework: experimental units, explanatory variables, treatments, and response variables. Knowing how these elements fit together enables the design of studies capable of producing trustworthy causal evidence.

Experimental Units

Experimental units are the entities to which treatments are applied. They represent the subjects or objects from which data are collected after treatment assignment.

Experimental Units: The individuals, animals, objects, or entities to which treatments in an experiment are applied.

Because experiments often deal with diverse contexts—such as people in medical trials or plots of land in agricultural studies—it is essential to identify experimental units precisely. Clear identification prevents confusion about what is being measured and ensures that results are interpreted consistently. In some cases, a distinction may appear between experimental units and subjects; although these terms often overlap, “subjects” is typically used when experimental units are human participants.

Explanatory Variables (Factors)

The explanatory variable is the variable that researchers manipulate intentionally to observe whether it causes a change in some outcome. In the terminology of experimental design, an explanatory variable is often referred to as a factor.

Explanatory Variable (Factor): A variable that is intentionally controlled or manipulated in an experiment to examine its effect on the response variable.

An experiment may include one factor or multiple factors. When multiple factors are present, researchers can explore how variables interact, allowing deeper insights into complex relationships. Factors are chosen carefully to address the study’s main research question.

Treatments

Treatments represent the specific conditions assigned to experimental units. They are formed by the levels of the explanatory variable or by combinations of levels when multiple factors exist.

Treatment: A specific condition applied to experimental units, formed by one level of a factor or a combination of levels across multiple factors.

A single factor with three different levels yields three treatments. If two factors each have two levels, the experiment contains four possible treatment combinations. Clearly identifying treatments ensures that comparisons between groups are meaningful and aligned with the study’s objectives. Treatments must be operationally defined so that they can be applied consistently across all units.

Response Variables

The response variable is the outcome measured after the treatment is applied. It represents the effect or result the experiment aims to assess.

Response Variable: The measurable outcome used to evaluate the effect of treatments on experimental units.

The response variable must be quantifiable, observable, and directly tied to the experiment’s purpose. In well-designed experiments, accurate and reliable measurement of the response variable is essential to making valid inferences. Researchers must ensure that measurements are made consistently across all experimental units to avoid introducing measurement bias.

How the Components Work Together

These four components operate in an integrated structure that allows an experiment to test a hypothesis and explore cause-and-effect relationships. A well-designed experiment typically follows this sequence:

Identify a research question requiring causal investigation.

Select appropriate experimental units that represent the context of interest.

Determine the explanatory variable(s) that will be manipulated.

Specify the treatments constructed from the levels of the explanatory variable(s).

Define and plan the measurement of the response variable, ensuring clarity and consistency.

Each step relies on a clear understanding of the previous components.

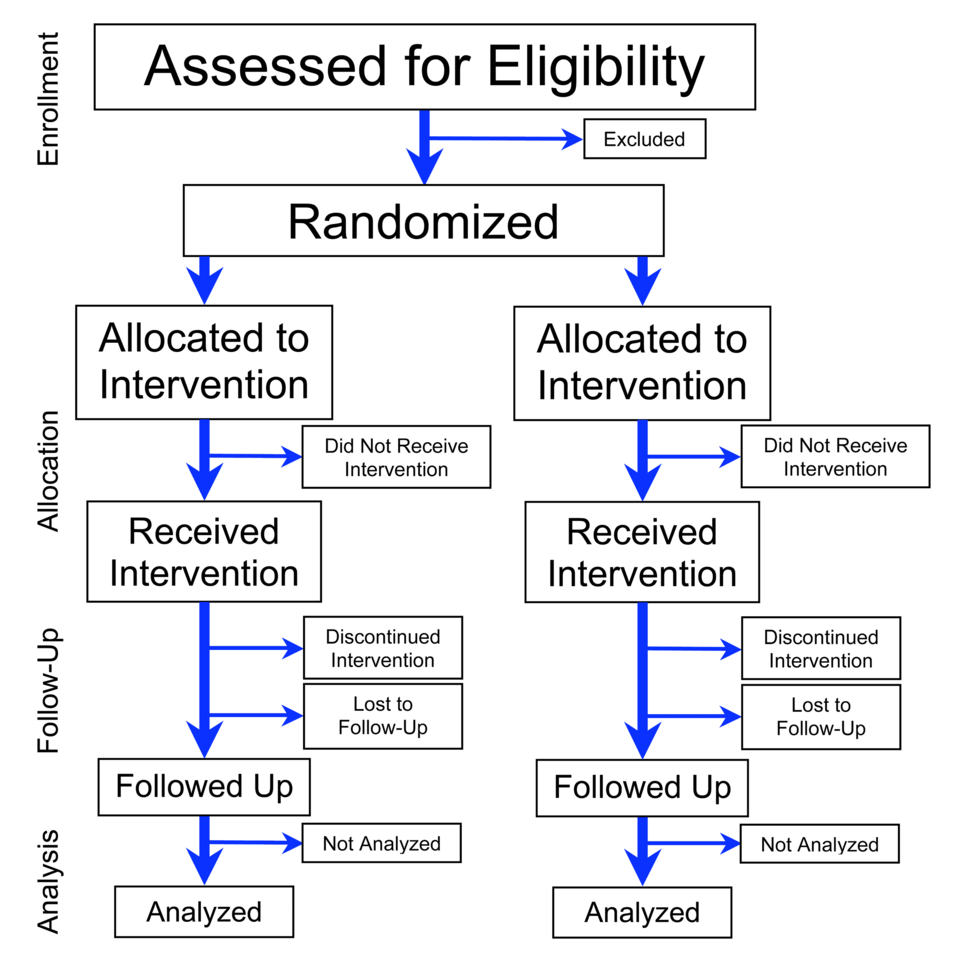

This flowchart visually connects experimental units, treatments, and response measurements within a randomized trial structure. It shows how individuals progress from eligibility screening through assignment and outcome assessment. Additional procedural stages extend beyond the syllabus but reinforce how these components function in real experimental designs. Source.

Without proper definition, the study may suffer from ambiguity, making results difficult to interpret or replicate.

Importance of Identifying Each Component

Clarity in identifying components supports the integrity of the entire experimental design. Proper specification:

Strengthens internal validity by ensuring treatments are applied correctly.

Improves the reliability of comparisons between treatment groups.

Allows other researchers to replicate the study accurately.

Helps students and practitioners evaluate whether the design can credibly support causal conclusions.

Ensures that statistical techniques used during analysis are appropriate for the type of data produced.

Identifying components also helps distinguish experiments from observational studies. Because experiments manipulate factors and assign treatments, they can provide direct evidence of causality when properly designed. Understanding the role of each component is essential for recognizing when a study genuinely qualifies as an experiment.

Structuring an Experiment Around These Components

To ensure strong design, researchers should consider the following when structuring an experiment:

The selection of experimental units must be deliberate and consistent with the purpose of the study.

Explanatory variables should align clearly with the hypothesis being tested.

Treatments must be administered uniformly to avoid systematic differences unrelated to the factor levels.

Response variables must be measurable and chosen to capture the intended outcomes accurately.

Each decision reinforces the experiment’s ability to isolate the effect of the explanatory variable, ensuring meaningful and interpretable results that align with AP Statistics expectations.

FAQ

A factor is a specific type of variable that the researcher deliberately manipulates in an experiment. Its levels are predetermined conditions chosen to test their effect on an outcome.

A general variable might simply be measured or observed, whereas a factor must be controlled and systematically applied to experimental units.

Factors also support structured comparisons, allowing meaningful evaluation of how different levels influence the response.

Researchers choose levels based on the range of conditions they wish to compare and the practical constraints of the study.

Considerations include:

• scientific relevance of each level

• available resources and time

• whether differences between levels are meaningfully distinct

• the need to avoid an excessive number of treatments, which can reduce the sample size per group

A balanced design helps ensure clear interpretation of the response variable.

Clear definition prevents ambiguity about what receives the treatment and what is being measured.

When units are defined beforehand:

• treatments can be applied consistently

• replication becomes meaningful

• comparisons across groups are valid

• sources of variation are better understood

Well-defined units also help avoid mistakenly treating clusters (such as classrooms or plots) as individuals, which can distort results.

Yes, an experiment may include more than one response variable when researchers want a more comprehensive view of the treatment effects.

Multiple responses can:

• capture different dimensions of the outcome

• reveal unintended effects of treatments

• provide richer evidence for evaluating effectiveness

However, each response must be measured reliably and interpreted separately to avoid misleading conclusions.

An operational definition specifies exactly how a treatment is implemented so that it is clear, repeatable and measurable.

This ensures that:

• all experimental units experience the treatment in the same way

• other researchers can replicate the study

• interpretations of treatment effects reflect the intended conditions rather than uncontrolled variation

Precise operational definitions help maintain internal validity and strengthen the credibility of findings.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A researcher conducts an experiment to test whether a new plant fertiliser increases the growth rate of tomato plants. The researcher applies the new fertiliser to half of the plants and uses no fertiliser on the other half. At the end of four weeks, the researcher measures the height of each plant.

a) Identify the experimental units.

b) State the explanatory variable.

c) State the response variable.

Question 1

a) Experimental units correctly identified as the tomato plants. (1 mark)

b) Explanatory variable stated as the type of fertiliser treatment (new fertiliser vs no fertiliser). (1 mark)

c) Response variable stated as the height or growth of the plants after four weeks. (1 mark)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A sports scientist wants to investigate whether a specific training programme improves sprint performance. Forty athletes volunteer to participate. Each athlete is randomly assigned to either the new training programme or the standard training routine. After six weeks, each athlete completes a timed 100-metre sprint, and their times are recorded.

a) Identify the treatments used in this experiment.

b) Explain why random assignment is important in this experiment.

c) Describe the response variable, and explain why it is suitable for this study.

d) Suggest one feature of the experimental design that could improve the reliability of the results.

Question 2

a) Treatments correctly identified as the new training programme and the standard training routine. (1 mark)

b) Clear explanation that random assignment helps create comparable groups, reduces bias, or controls for confounding variables. (1–2 marks)

c) Response variable identified as the 100-metre sprint time and explanation that it directly measures sprint performance. (1–2 marks)

d) A reasonable suggestion such as increasing sample size, standardising conditions, or replicating the study, with justification. (1 mark)