AP Syllabus focus:

‘VAR-4.E.1: Elaborate on the definition of independent events, where the occurrence of event A does not affect the probability of event B. This section aims to clarify the concept of independence in probability, providing a foundational understanding that is crucial for calculating probabilities related to independent events.’

Understanding Independent Events

Independent events form a foundational idea in probability, emphasizing situations where knowing that one event occurred provides no information about whether another event will occur. This concept supports accurate probability calculations in many statistical contexts.

What Independence Means in Probability

When studying random processes, patterns often emerge, and it becomes essential to determine whether these patterns reflect meaningful relationships or simply chance. One key relationship explored in probability is independence, which tells us whether two events influence one another. Independence helps determine when the probability of one event should remain unchanged, even when another event is known to have happened.

Independent Events: Two events are independent if the occurrence of one event does not change the probability of the other event occurring.

In probability contexts, independence is not assumed automatically; it must be established based on information about the scenario or through known probability structures. Once independence is confirmed, it becomes a powerful simplifying tool for calculating probabilities involving multiple events.

Characterizing Independent Events

Independence centers on the stability of probabilities under additional information. If event A and event B are independent, the likelihood of B remains identical whether or not A occurs. This relationship is reciprocal: the probability of A also remains unchanged by the occurrence of B. Understanding this symmetry is essential because it emphasizes that independence is a mutual property, not a one-directional claim.

A useful way to conceptualize independence is to contrast it with dependence. When events are dependent, the outcome of one provides meaningful information about the outcome of the other. For independent events, no such information is gained. The probability structure of one event remains fully intact, regardless of knowledge about the other.

Independent events often arise in repeated trials of the same random process, such as multiple tosses of a fair coin or rolls of a fair die.

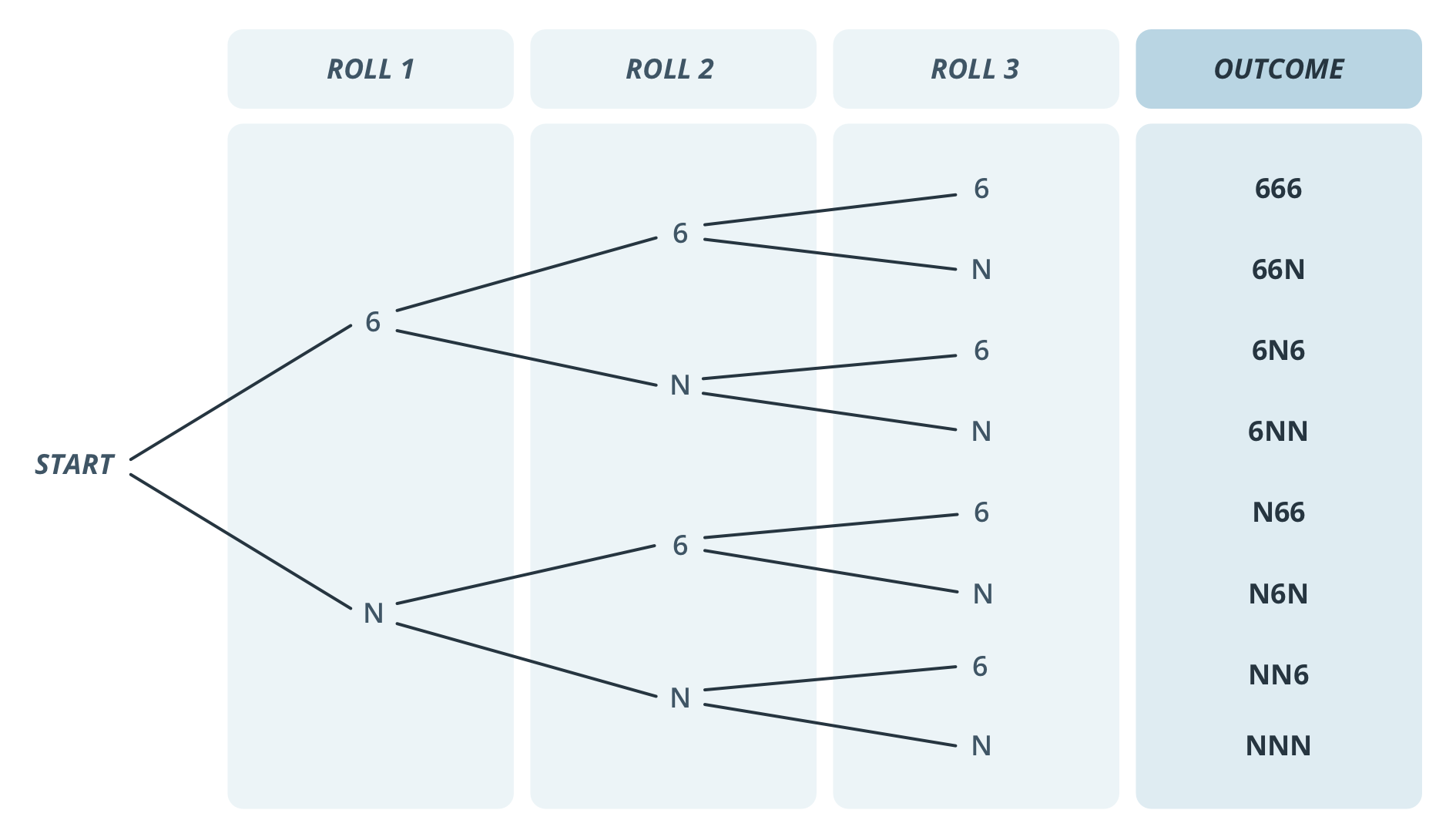

Tree diagram for three independent die rolls, with branching that repeats the same structure at each stage because each roll is independent. Each complete path represents a possible sequence such as 6NN. This visual highlights how independent events combine through repeated, unaffected probability stages. Source.

Mathematical Expression of Independence

While the meaning of independence can be stated verbally, probability theory formalizes the idea. AP Statistics students should understand how independence is represented mathematically because this expression is foundational for later applications involving joint probabilities.

EQUATION

= Probability that both events occur

= Probability of event A

= Probability of event B

This equation expresses that, for independent events, the probability of both events occurring together equals the product of their individual probabilities. This relationship works only when events are independent; if the product does not equal the joint probability, the events are not independent. Because of its importance, this condition becomes a standard test for independence in statistical analysis.

The equation also reinforces the conceptual definition: if learning that A occurred changes the expected frequency of B, then multiplying their individual probabilities will not correctly represent the joint probability. Therefore, independence must be confirmed before using this condition in calculations.

Recognizing When Events Are Independent

Students must be able to recognize independence conceptually and mathematically. Identifying independence typically involves one of the following:

Determining that the context explicitly states independence.

Evaluating whether knowing one event affects the likelihood of the other.

Using probability values to verify the independence condition.

Understanding the underlying random mechanism to decide whether outcomes influence each other.

Contextual reasoning plays an important role. Two events may appear unrelated, but unless it is known that the outcome of one does not alter the probability of the other, independence should not be assumed. AP Statistics emphasizes careful justification rather than intuitive guesses.

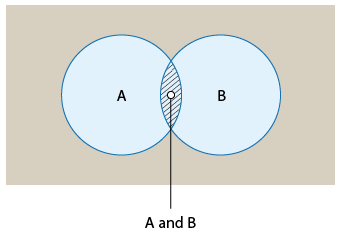

The event ‘A and B’ (the intersection) consists of outcomes that belong to both A and B at the same time.

Venn diagram illustrating events A and B with their overlapping region representing A ∩ B. This figure clarifies the geometric meaning of the intersection used when evaluating independence. While it does not itself indicate independence, it displays the region whose probability is compared with . Source.

Why Independence Matters

Independence is central to the structure of probability because it allows simplification of otherwise complex calculations. Many statistical methods rely on the assumption of independent events or independent random variables. When independence holds, combining probabilities becomes more straightforward, supporting clearer interpretation of outcomes and stronger statistical conclusions.

Independence also forms the basis for later probability rules, including those involving the multiplication of probabilities for independent events. Without establishing independence, these rules cannot be used reliably. Thus, developing a strong understanding of independent events is fundamental for progressing into more advanced statistical reasoning.

Indicators of Independence in Real-World Contexts

Although AP Statistics avoids relying solely on intuition, real-world situations often provide clues about independence. These situations may involve:

Physical processes where one outcome cannot influence another

Random mechanisms specifically designed to maintain independence

Scenarios where trials are repeated under identical conditions

These clues help develop informed expectations about independence, but probability verification remains necessary when data or outcomes must be analyzed mathematically.

Summary of Key Features of Independent Events

To consolidate an operational understanding of independence, students should remember the following essential points:

Independence means no influence between the outcomes of events.

Probabilities remain unchanged when independence is present.

Mathematical confirmation relies on verifying the independence condition.

Independence must be justified, not assumed, unless explicitly stated in the scenario.

Through these principles, independent events become a fundamental tool for reasoning accurately about probability in a wide range of statistical applications.

FAQ

Independence can be inferred from contextual clues. If the description establishes that the mechanism generating each event operates separately, this strongly supports independence.

You may also consider whether knowing one event would logically influence expectations about the other. If no plausible pathway for influence exists, the assumption of independence can be reasonable, though it must still be justified.

Yes. Events may appear related superficially, but independence concerns whether one event alters the probability of the other.

For example, two measures that occur in the same setting could still be independent if the underlying processes do not interact.

Independence focuses on the behaviour of probabilities, not on whether events feel intuitively connected.

Mutually exclusive events cannot occur at the same time, which means their intersection is impossible. Independent events, however, can occur together.

Key distinctions include:

• Mutually exclusive: one event rules out the other.

• Independent: one event does not affect the probability of the other.

Mutually exclusive events cannot be independent unless one has probability zero.

A frequent misconception is assuming independence simply because events occur in different categories or at different times. Context matters more than appearance.

Another misconception is thinking that independence is symmetric only in notation; in reality, independence inherently implies mutual non-influence in both directions.

Students may also incorrectly assume that repeated trials are always independent, even when conditions change between trials.

Independence shapes how data should be modelled and interpreted. When observations are not independent, patterns may be overstated or understated.

In empirical studies, independence affects:

• How confidently patterns can be generalised

• Whether probability rules apply appropriately

• How variability is explained

Recognising dependence prevents misinterpretation of relationships that arise purely from shared underlying factors.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A fair coin is flipped, and a fair six-sided die is rolled.

(a) State whether the events “coin lands on heads” and “die shows a 4” are independent.

(b) Justify your answer.

Question 1

(a) 1 mark

States that the events are independent.

(b) 1–2 marks

Correct justification that the outcome of the coin flip does not affect the outcome of the die roll (1 mark).

May also earn a mark for stating that the probability of the die showing a 4 remains 1/6 regardless of the coin outcome, or equivalent correct reasoning (1 mark).

Maximum: 3 marks

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A survey investigates whether students’ preferred study time (Morning or Evening) is related to whether they take notes digitally (Yes or No). The following probabilities are known:

P(Morning) = 0.40

P(Digital) = 0.55

P(Morning and Digital) = 0.22

(a) Determine whether the events Morning and Digital are independent. Show your working.

(b) Interpret your conclusion in the context of the study.

(c) Explain one reason why incorrectly assuming independence could lead to misleading conclusions about students’ study habits.

Question 2

(a) 2–3 marks

Calculates P(Morning) × P(Digital) = 0.40 × 0.55 = 0.22 (1 mark).

Compares this product with the given P(Morning and Digital) = 0.22 (1 mark).

Correctly concludes that the events are independent because the values match (1 mark).

(b) 1–2 marks

States that knowing a student studies in the morning does not change the probability that they take digital notes (1 mark).

Provides clear contextual interpretation, such as “Morning students are no more or less likely to take digital notes than Evening students” (1 mark).

(c) 1–2 marks

Explains that assuming independence when it does not hold could lead to inaccurate predictions or poor study-resource planning (1 mark).

Provides an additional, relevant contextual reason (e.g., misinterpretation of relationships between habits) (1 mark).

Maximum: 6 marks