AP Syllabus focus:

‘The Court has sometimes allowed restrictions on minority civil rights and at other times has protected minority groups under equal protection.’

Understanding why the Supreme Court sometimes upholds laws that burden minority groups and other times strikes them down requires focusing on equal protection doctrine, judicial deference, and how the Court weighs governmental objectives against individual equality.

The Constitutional Hook: Equal Protection

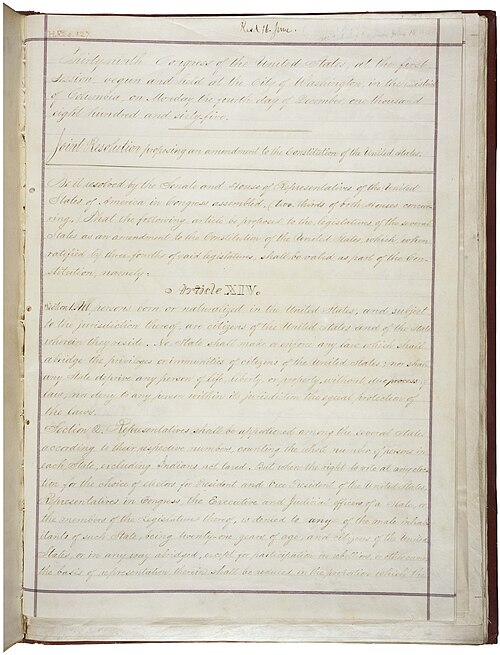

A high-resolution scan of the Fourteenth Amendment document (National Archives), showing the constitutional text that grounds modern equal protection doctrine. Using the original document reinforces that equal protection is a constitutional command directed at government action, not just a policy idea. Source

The key constitutional tool is the Fourteenth Amendment, which limits state action that treats people differently without adequate justification.

Equal protection clause: The Fourteenth Amendment guarantee that states must treat similarly situated people alike; government classifications must be justified under the appropriate level of judicial scrutiny.

Equal protection claims often involve classifications—laws that sort people by race, ethnicity, national origin, sex, or other traits—or laws that are neutral on their face but have unequal effects.

How the Court Chooses Between Restricting vs. Protecting Minority Rights

Step 1: Identify the classification (or lack of one)

Courts ask whether the law:

Explicitly classifies by a trait (e.g., race-based eligibility)

Uses a proxy that effectively targets a group

Is facially neutral but has disparate impact (unequal outcomes)

A disparate impact alone is usually not enough; challengers typically must also show discriminatory intent to trigger heightened constitutional concern.

Step 2: Apply the level of scrutiny

The Court’s willingness to protect minorities often depends on the level of scrutiny attached to the classification:

Strict scrutiny (hardest to satisfy): typically for race and national origin

Government must show a compelling interest

The law must be narrowly tailored

Intermediate scrutiny: typically for sex

Government must show an important interest

Means must be substantially related

Rational basis review (most deferential): most other classifications

Government needs a legitimate interest

Law must be reasonably related (often upheld)

Step 3: Consider context and institutional concerns

Even with equal protection, outcomes can shift when the Court emphasises:

Public safety and emergency claims

Separation of powers and deference to elected branches

Concerns about courts managing complex policy areas (administration, security, elections)

When the Court Has Allowed Restrictions on Minority Rights

Deference during perceived crises

Historically, the Court has sometimes accepted broad government claims about national security or wartime necessity, allowing major burdens on minorities. In such periods, the Court may:

Credit executive/legislative judgments about threats

Downplay individual harms as “incidental” to security

Treat challenges as second-guessing military or emergency policy

A commonly cited example is Korematsu v. United States (1944), where the Court upheld Japanese American internment during World War II—illustrating how deference can lead to severe restrictions even on vulnerable minorities.

A documentary photograph of a guard tower and barbed wire at Manzanar, one of the War Relocation Authority incarceration sites for Japanese Americans during World War II. The image captures how national-security justifications can translate into broad deprivations of liberty, helping explain why courts sometimes defer heavily during perceived emergencies. Source

Low scrutiny or weak proof of discrimination

Restrictions are more likely to be upheld when:

The law triggers only rational basis review

Plaintiffs cannot prove intentional discrimination

The Court views the classification as administratively convenient and not invidious

Majority rule and political process assumptions

At times, the Court assumes that the political process can correct unfairness, especially when:

A group is not treated as a “suspect” class doctrinally

The burden is framed as economic or regulatory rather than status-based

The Court prioritises stability and uniform rule application

When the Court Has Protected Minority Rights Under Equal Protection

Heightened scrutiny for suspect or quasi-suspect classifications

Protection is strongest when strict or intermediate scrutiny applies. In practice, the Court is more likely to strike down laws when it sees:

A history of discrimination against the targeted group

Stereotyping or status-based exclusions

A mismatch between the government’s stated goal and the law’s real operation

Detecting unconstitutional purpose

Even facially neutral laws can be invalidated if challengers show a discriminatory purpose, supported by:

Legislative history (statements, debates)

Unusual procedural departures

Pattern of effects plus contextual evidence suggesting targeting

Requiring “fit” between means and ends

Equal protection analysis pushes the government to justify not just its goal, but the precision of its approach. The Court tends to protect minority rights when:

Government interests are asserted broadly but implemented bluntly

Less discriminatory alternatives appear available

The law looks overinclusive (sweeps in too many) or underinclusive (misses many similarly situated)

What to Track in Any Equal Protection Case

Who is classified, and how?

What level of scrutiny applies, and why?

What interest does the government claim?

How tight is the connection between the law and that interest?

Is there evidence of discriminatory intent, not just unequal outcomes?

FAQ

Courts infer intent from circumstantial evidence, such as sequencing, departures from normal procedure, contemporaneous statements, and whether the effects were foreseeable and unusually concentrated.

Yes. A formally uniform rule can still violate equal protection if it is administered selectively or designed to burden a group, supported by proof of intentional discrimination.

It is a more searching form of rational basis review where the Court is sceptical of the government’s justification. It can matter when animus appears to motivate a classification.

Federal equal protection limits are generally applied through the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process Clause (a “reverse incorporation” idea), often using similar scrutiny frameworks.

Cases can be dismissed for lack of standing, mootness, ripeness, or failure to show a concrete injury—threshold rules that can prevent courts from reaching equal protection analysis.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Explain what “strict scrutiny” requires in an equal protection case.

1 mark: Identifies that the government must show a compelling governmental interest.

1 mark: States the law must be narrowly tailored (or the least restrictive means) to achieve that interest.

(6 marks) A state adopts a policy that uses a facially neutral criterion for a public benefit, but it disproportionately excludes a racial minority group. Using equal protection principles, explain two reasons the Court might uphold the policy and two reasons it might strike it down.

1 mark: Upheld—disparate impact alone is usually insufficient without proof of discriminatory intent.

1 mark: Upheld—if reviewed under rational basis, the state need only show a legitimate interest and a reasonable relationship.

1 mark: Struck down—evidence of discriminatory intent (e.g., legislative history/procedural departures) can trigger heightened concern.

1 mark: Struck down—if the policy functions as a proxy for race, strict scrutiny may apply.

2 marks: Accurate application tying the above reasons to equal protection analysis (classification/scrutiny/fit), clearly linking facts to outcomes.