AP Syllabus focus:

‘State laws and Court rulings using “separate but equal” restricted African Americans’ access to schools, hotels, restaurants, and other facilities.’

This subtopic explains how the “separate but equal” doctrine legitimised racial segregation through state law and Supreme Court approval, producing systematic denial of access to public and private services despite formal constitutional guarantees.

The “separate but equal” doctrine: purpose and effect

Separate but equal functioned as a legal rationale for racial segregation: governments could require separate facilities for Black and white Americans while claiming constitutional compliance if the facilities were “equal.” In practice, the doctrine enabled broad exclusion and second-class treatment.

Key terminology

Jim Crow laws: State and local laws (especially in the South, late 1800s–mid 1900s) mandating racial segregation and reinforcing racial hierarchy in public facilities, education, employment practices, and civic life.

“Separate but equal” was not merely social custom; it was embedded in enforceable rules affecting everyday participation in public life.

Constitutional framing: equal protection and state power

Segregation regimes developed within a federal system where states historically regulated many “police powers” (health, safety, public order). Supporters of segregation argued that separation was a reasonable exercise of those powers and did not violate the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause so long as states offered nominally comparable facilities.

How courts enabled denial of equal access

When courts accepted “separate but equal,” they effectively:

Treated racial separation as constitutionally permissible rather than inherently unequal

Narrowed the meaning of equal protection to allow formal, on-paper equality while ignoring real-world inequality

Reduced incentives for states to provide genuinely equivalent services, since equality was weakly enforced

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) and judicial validation

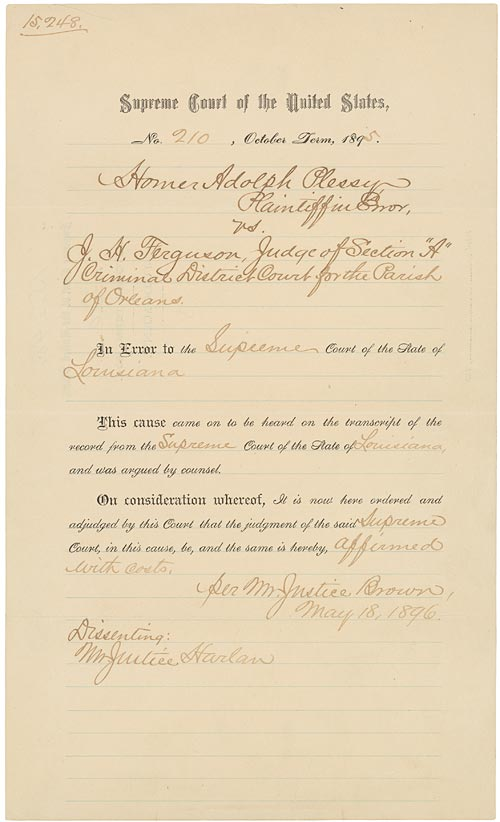

Photograph of the official Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) judgment, a primary document from the Supreme Court’s records. Using the original decision helps students connect the abstract doctrine of “separate but equal” to the concrete legal authority that upheld state-imposed segregation. It also reinforces how Court rulings can shape the practical meaning of equal protection in a federal system. Source

The doctrine is most closely associated with Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), where the Supreme Court upheld Louisiana’s segregated railroad cars. The Court’s reasoning reflected two critical moves:

Separation does not imply inferiority (the Court claimed any stigma came from how Black citizens “chose” to interpret segregation)

The Constitution was interpreted as permitting social separation while guaranteeing only limited forms of legal equality

This ruling gave constitutional cover to widespread segregation statutes, signalling that many forms of race-based separation would survive judicial review.

Denial of equal access in practice: schools, lodging, dining, and more

Under “separate but equal,” African Americans faced extensive barriers to equal participation, including exclusion, inferior services, and coercive compliance. The syllabus emphasis is that state laws and Court rulings together restricted access to:

Schools: segregated systems with major disparities in funding, buildings, materials, transportation, and teacher pay

Hotels and lodging: legal or customary refusal of service, separate inferior accommodations, or outright exclusion in many locations

Restaurants and public dining: segregated seating, separate entrances, take-out-only rules, or denial of service

Other facilities: theatres, parks, hospitals, restrooms, drinking fountains, libraries, beaches, and cemeteries

Even where a “separate” option existed, it was frequently unequal in quality, availability, and geographic convenience, producing practical denial of access.

How segregation was enforced and normalised

Segregation worked through overlapping legal and political mechanisms that made challenges difficult and costly.

Legal and administrative tools

Statutory mandates: explicit segregation requirements in state/local codes

Licensing and regulation: conditioning business licences or public contracts on compliance with segregation norms

Selective enforcement: policing Black citizens more aggressively for alleged violations of “order,” loitering, or trespass

Procedural barriers: court systems and local juries that made remedies slow, expensive, and uncertain

Social and economic pressures (supported by law)

Retaliation risks (job loss, eviction, violence) discouraged individuals from contesting exclusion

Segregation shaped consumer access, mobility, and opportunity, reinforcing racial inequality beyond any single facility

Why “separate but equal” mattered for American government

“Separate but equal” shows how rights on paper can be narrowed by institutional interpretation. When courts defer to states or accept formalistic standards, constitutional protections may coexist with discriminatory governance. The doctrine also illustrates how Supreme Court legitimacy can stabilise contested social arrangements by signalling what governments may do without triggering constitutional consequences.

FAQ

It often reached private businesses through public accommodation rules, licensing, and local ordinances.

Where not explicit in statute, customs were reinforced by selective enforcement of trespass and “order” laws.

Equality was weakly measured and poorly enforced.

Local officials controlled budgets and administration, and courts often accepted minimal compliance, allowing large gaps in quality, distance, and availability.

Segregated rail and bus systems constrained where people could safely go and when.

It restricted access to jobs, education, medical care, and commerce by raising the costs and risks of movement.

Local governments operationalised segregation through:

Ordinances (zoning, business rules)

Police practices

Permits and inspections

States often supplied the legal backbone, while localities ensured daily compliance.

Segregation limited access to meeting spaces, information networks, and public forums.

It also signalled unequal civic standing, discouraging mobilisation and making collective action riskier and more costly.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Describe what the “separate but equal” doctrine allowed state governments to do.

1 mark: Identifies that states could legally require racial segregation in public facilities/services.

1 mark: Notes the constitutional claim that segregation was permissible if facilities were supposedly “equal” (even if not equal in practice).

(6 marks) Explain how state laws and court rulings using “separate but equal” denied African Americans equal access to public life.

1 mark: Explains that laws mandated segregation in facilities (e.g., schools, hotels, restaurants).

1 mark: Explains that court approval (e.g., Plessy v. Ferguson) legitimised these laws under the Constitution.

1 mark: Explains how “equality” was treated formally/on paper rather than substantively in real conditions.

1 mark: Gives a specific example of denial of access or inferior provision (education, lodging, dining, or other facilities).

1 mark: Describes an enforcement mechanism (policing, licensing, selective enforcement, or procedural barriers).

1 mark: Links the system to broader exclusion from civic or economic participation (restricted mobility/opportunity).