AP Syllabus focus:

‘In some cases, the Court has upheld majority rights by limiting or prohibiting certain forms of majority‑minority districting.’

Redistricting can either protect minority voting power or violate equal protection by sorting voters by race. Supreme Court doctrine tries to balance representation goals with the constitutional rights of voters—especially when race becomes the dominant mapmaking tool.

Core idea: balancing representation and equal protection

Redistricting sets district boundaries after the census. When mapmakers use race to shape districts, the Court evaluates whether the plan advances lawful representation goals or instead burdens voters’ rights under the Fourteenth Amendment Equal Protection Clause.

Majority‑minority districts: what they are and why they matter

Majority‑minority district: an electoral district in which a racial or ethnic minority group makes up a numerical majority of the voting‑age population, increasing the likelihood that the group can elect preferred candidates.

Majority‑minority districts are often justified as a response to vote dilution concerns, but the Constitution limits how explicitly race may drive district lines.

When the Court limits majority‑minority districting to protect majority rights

The modern doctrine developed when the Court became concerned that creating oddly shaped, race‑conscious districts can classify citizens by race and stigmatise voters, even if the intent is to improve minority representation.

Racial gerrymandering claims (Shaw‑type claims)

Racial gerrymandering: drawing district lines where race predominates over neutral criteria, triggering heightened constitutional scrutiny under equal protection.

A racial gerrymandering claim is not simply “politics as usual.” It alleges that the state treated race as the key sorting principle for voters.

The “predominance” question

Courts ask whether race predominated over traditional districting principles, such as:

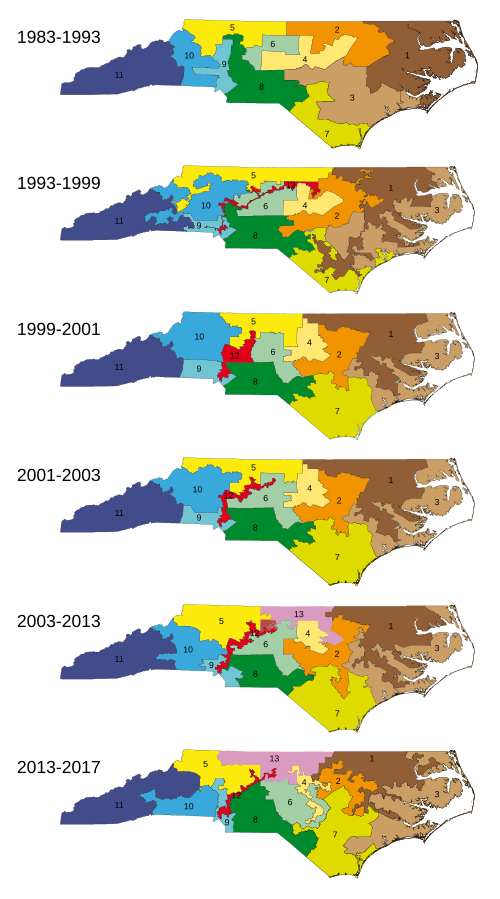

Multi-year map series of North Carolina congressional districts that highlights how district geometry can become unusually contorted. By comparing shapes across years, students can see why courts treat departures from compactness and other traditional criteria as potential evidence that a legislature subordinated neutral principles to a race-based (or other) sorting goal. This is a visual bridge between the “predominance” test and the real-world appearance of contested districts. Source

Compactness and contiguity

Respecting political subdivisions (counties/cities)

Preserving communities of interest

Avoiding unnecessary splits of precincts or municipalities

Evidence can include legislative intent, demographic targets (e.g., fixed minority percentages), and district shapes that cannot be explained by neutral criteria.

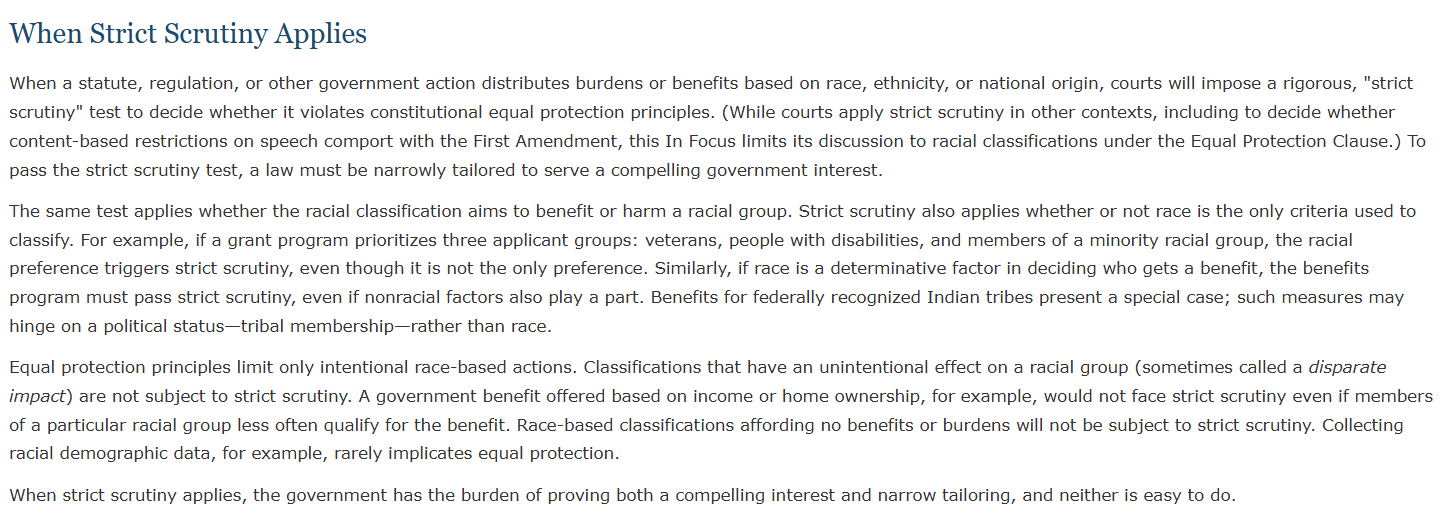

If race predominates: strict scrutiny

When race is the predominant factor, the plan must satisfy strict scrutiny:

Congressional Research Service overview explaining when strict scrutiny applies to race-based governmental action under the Equal Protection Clause and what the government must prove (a compelling interest and narrow tailoring). It supports the doctrinal “if race predominates → strict scrutiny” move in your notes with an authoritative, nonpartisan framing. Used alongside the district maps, it helps students connect the legal test to the kind of evidence (like district shape) that can trigger it. Source

The state must have a compelling governmental interest

The use of race must be narrowly tailored to that interest

In practice, states frequently argue that compliance with the Voting Rights Act (VRA) is the compelling interest. The Court, however, requires more than a general desire to avoid lawsuits; states need a strong basis in evidence that the VRA actually requires the race‑based lines used.

Key Supreme Court themes and cases

These cases illustrate how the Court may uphold “majority rights” (equal protection rights of all voters) by limiting majority‑minority districting when it becomes racial sorting.

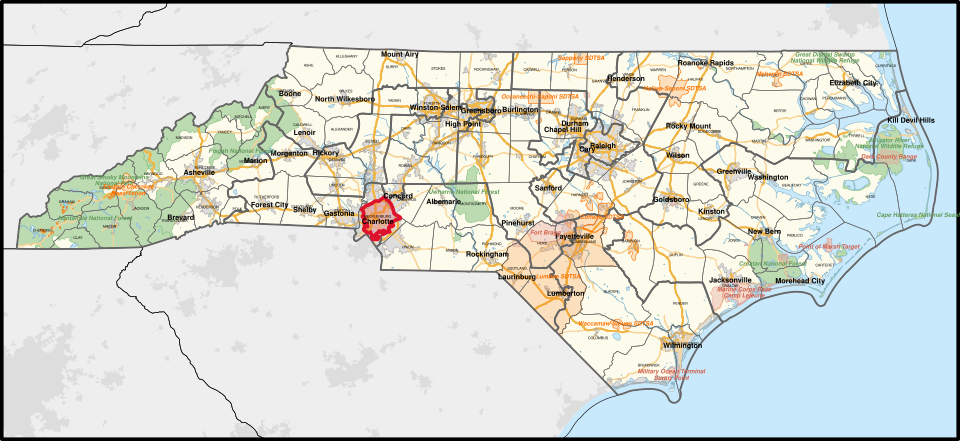

Shaw v. Reno (1993): race as a constitutional harm

Map of North Carolina’s 12th congressional district highlighted against surrounding geography and boundaries. The district’s highly non-compact shape is the kind of visual evidence courts and litigants use when arguing that race (rather than neutral criteria) predominated in the line-drawing. In AP Gov terms, it helps connect Shaw’s abstract equal-protection harm to what race-conscious district design can look like on the ground. Source

The Court held that bizarrely shaped, race‑based districts can trigger equal protection concerns even without an explicitly discriminatory purpose. The harm is the state’s message that race defines political identity.

Miller v. Johnson (1995): race cannot dominate without justification

The Court reinforced the predominance test and stressed that compliance with federal law does not give states unlimited authority to prioritise race. Traditional districting principles must not be subordinated absent strict‑scrutiny justification.

Bush v. Vera (1996): narrow tailoring matters

Even assuming a compelling interest, the Court signalled that states cannot use race more than necessary. Overly aggressive racial line‑drawing fails if it is not closely connected to a real legal requirement.

Alabama Legislative Black Caucus v. Alabama (2015): mechanical racial targets are suspect

The Court criticised the use of rigid racial percentages (for example, treating a particular minority share as mandatory in multiple districts). Narrow tailoring requires district‑by‑district reasoning, not automatic racial quotas.

Cooper v. Harris (2017): “racial targets” vs legitimate goals

The Court invalidated districts where race predominated without sufficient VRA justification, emphasising that states must show why the VRA required the chosen design rather than a less race‑focused alternative.

Practical takeaway for AP Gov

The Court’s limits reflect a tension:

Majority‑minority districts can be a tool to protect minority electoral opportunity.

But when districting treats voters primarily as members of racial blocs, the Court may view that as unconstitutional racial classification and will sometimes limit or prohibit such designs to protect equal protection rights for all voters, including majority voters.

FAQ

Courts look for evidence that the legislature used race directly (racial targets, demographic thresholds, instructions to map‑drawers), not merely party data.

They also assess whether district features are better explained by political goals or by racial sorting.

Common evidence includes:

Draft maps and emails showing racial targets

Expert analysis correlating boundary choices with race

Testimony about prioritising minority percentages

Shapes and splits inconsistent with neutral criteria

Yes, under some applications of the VRA, a state may need to avoid minority vote dilution where conditions support a minority community’s opportunity to elect preferred candidates.

But the Court still requires careful, district‑specific justification.

Rigid thresholds can function like racial quotas.

Courts view mechanical targets as evidence that race predominated and as a failure of narrow tailoring because they ignore local political and demographic realities.

Typically, courts order:

A new map drawn by the legislature under judicial deadlines, or

A court‑supervised remedial map if the legislature fails to act promptly.

Remedies aim to remove race as the predominant driver while preserving lawful districting criteria.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Identify one constitutional basis the Supreme Court uses to evaluate challenges to majority‑minority districts, and briefly explain how it applies.

1 mark: Identifies Fourteenth Amendment Equal Protection Clause (or equal protection).

1 mark: Explains that when race predominates in drawing districts, the Court can treat it as a racial classification and apply strict scrutiny.

(5 marks) Explain how the Supreme Court determines whether a majority‑minority district is unconstitutional racial gerrymandering. In your answer, refer to (a) the predominance inquiry and (b) strict scrutiny.

1 mark: Describes the predominance test (race must be shown to dominate mapmaking).

1 mark: Notes comparison against traditional districting principles (e.g., compactness, respecting boundaries).

1 mark: States that if race predominates, strict scrutiny applies.

1 mark: Defines a compelling interest (often argued as VRA compliance with strong evidential basis).

1 mark: Explains narrow tailoring (race used no more than necessary; no mechanical racial targets).