AP Syllabus focus:

‘Other Court decisions held that race‑based school segregation violates the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause.’

School segregation cases show how the Supreme Court can transform constitutional meaning. After decades of legally enforced separation, the Court ruled that segregated public education violates equal protection and then supervised uneven, contested implementation.

Constitutional basis: equal protection and state action

The modern anti-segregation decisions rest on the Fourteenth Amendment, which limits state governments and local school districts.

Equal protection clause: The Fourteenth Amendment requirement that states provide the equal protection of the laws, barring unjustified discrimination by government.

To trigger equal protection review, there must be state action (government policy or official enforcement), which is why the key cases focus on public schools and government-run systems.

The turning point: Brown v. Board of Education

Brown (1954): segregation is inherently unequal

In Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the Court held that race-based school segregation violates the equal protection clause.

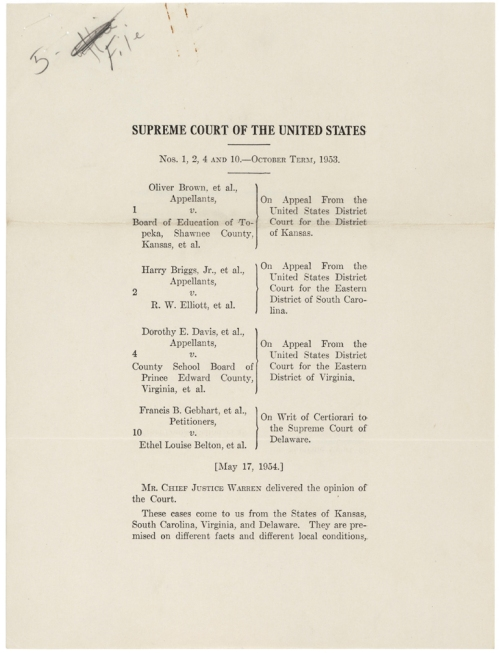

First page from the National Archives’ scan of the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education opinion (May 17, 1954). Using the actual opinion helps you link the Court’s equal-protection reasoning to primary evidence, not just a later summary. It also reinforces why Brown became the doctrinal “turning point” for Fourteenth Amendment equality in public education. Source

The core reasoning was that separating children by race in public education is inherently unequal, even if tangible resources appear similar, because segregation stamps minority students with a badge of inferiority and undermines equal citizenship.

Key constitutional impacts:

Rejected the idea that equality can be satisfied by formal “separation”

Treated education as central to equal opportunity and democratic participation

Made racial classifications by government in schooling constitutionally suspect

Brown II (1955): remedy and timing

In Brown II (1955), the Court addressed remedies, directing districts to desegregate with “all deliberate speed.” This phrase mattered because it:

Required compliance but allowed delays justified by local implementation claims

Shifted major enforcement to federal district courts, which issued detailed orders

Enforcing desegregation: subsequent Court decisions

After Brown, the Court decided additional cases clarifying what unconstitutional segregation is and what desegregation requires in practice.

De jure segregation: Segregation created or maintained by law or official government action, as opposed to separation resulting from private choices or housing patterns.

Compulsory compliance and federal supremacy

Cooper v. Aaron (1958): States cannot nullify Supreme Court rulings; state officials are bound by the Constitution as interpreted by the Court. This strengthened federal judicial authority when states resisted integration.

From “no segregation” to “real desegregation”

Green v. County School Board (1968): “Freedom-of-choice” plans were insufficient if they did not actually dismantle segregated systems. Districts had an affirmative duty to eliminate segregation “root and branch,” not merely remove explicit racial language.

Tools courts could require

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg (1971): Federal courts could order robust remedies, including busing, redrawing attendance zones, and racial targets as starting points, to eliminate de jure segregation.

Photograph of Black and white students riding a school bus in Charlotte, North Carolina (Feb. 21, 1973), a city closely associated with court-ordered busing after Swann. The image concretizes what “busing” meant as a remedial tool—an operational policy choice used to alter school enrollment patterns. It pairs well with doctrinal notes by showing how constitutional remedies translate into day-to-day governance. Source

The decision treated remedies as flexible, tied to the scope of the constitutional violation.

Limits on remedies across district lines

Milliken v. Bradley (1974): Courts generally could not impose interdistrict desegregation plans (e.g., city-suburb busing) without proof that multiple districts had engaged in de jure segregation causing the harm. This limited metropolitan-wide solutions and shaped long-term patterns of school separation.

What students should be able to do with these cases

Connect school segregation to the equal protection clause and explain why public schools count as state action

Distinguish finding a violation (de jure segregation) from designing a remedy (court-ordered desegregation tools and limits)

Explain how “segregation declared unconstitutional” required multiple rulings: one announcing the rule (Brown) and others defining enforcement, obligations, and boundaries of judicial power

FAQ

Because public education is closely tied to civic participation and opportunity.

The Court’s reasoning treated unequal access in schooling as uniquely harmful to equal citizenship, not merely an ordinary government service.

They often relied on multiple forms of proof:

The official structure of school assignments and boundary lines

The cumulative effects of enforced separation on students’ status and opportunities

Historical patterns showing the government built and maintained dual systems

They used ongoing supervision rather than a one-time ruling.

Courts could require plans, set deadlines, demand reporting, and modify orders when districts failed to produce actual integration.

Ending segregation targets government-imposed separation (de jure systems).

Integration is a broader outcome that may be affected by housing, district boundaries, and demographic change even after explicit legal segregation ends.

They raised questions about responsibility and causation across separate school districts.

If a suburb was not proven to have contributed to the constitutional violation, courts were far less willing to impose cross-district solutions affecting its schools and voters.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Explain how the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause was used by the Supreme Court to declare race-based school segregation unconstitutional.

1 mark: Identifies that the equal protection clause requires states to treat individuals equally under the law and restricts state discrimination.

1 mark: Links this to public schooling by stating that state-imposed racial segregation in schools denies equal protection (i.e., is unconstitutional).

(5 marks) Describe how Supreme Court decisions after Brown shaped the implementation of school desegregation. In your answer, refer to at least two post-Brown cases.

1 mark: Describes Brown as establishing that de jure school segregation violates equal protection.

2 marks: Accurate explanation of two post-Brown cases (1 mark each), e.g.:

Brown II: remedies and “all deliberate speed”/role of lower federal courts.

Cooper v Aaron: states must comply; federal supremacy.

Green: ineffective “freedom-of-choice” plans; affirmative duty.

Swann: permissible tools such as busing/zoning.

Milliken: limits on interdistrict remedies absent interdistrict violation.

1 mark: Explains how these cases affected implementation (expanded duties/tools or imposed limits).

1 mark: Overall coherence and clear linkage to desegregation practice (not merely listing cases).