AP Syllabus focus:

‘Some government interests may justify restricting individual rights—for example, limiting speech when it presents a danger to public safety.’

Rights in the Bill of Rights are powerful but not absolute. Courts often allow limits when the government can justify regulation as necessary to protect safety, order, and other important public interests.

When the Government May Limit a Right

Constitutional rights are enforced through courts, which ask whether a restriction is justified by a sufficiently important government interest and whether the law is properly designed.

Key principle: balancing rights and interests

Courts generally accept that government can restrict rights when:

the government’s objective is legitimate (and sometimes especially weighty), and

the restriction is not broader than needed to accomplish that objective.

This is why, for example, the government may sometimes limit speech if it creates a danger to public safety (such as inciting imminent violence).

The Court’s Main Tools for Evaluating Limits

Different rights and contexts trigger different tests, but the core question is always whether the Constitution permits the government’s chosen means to pursue its ends.

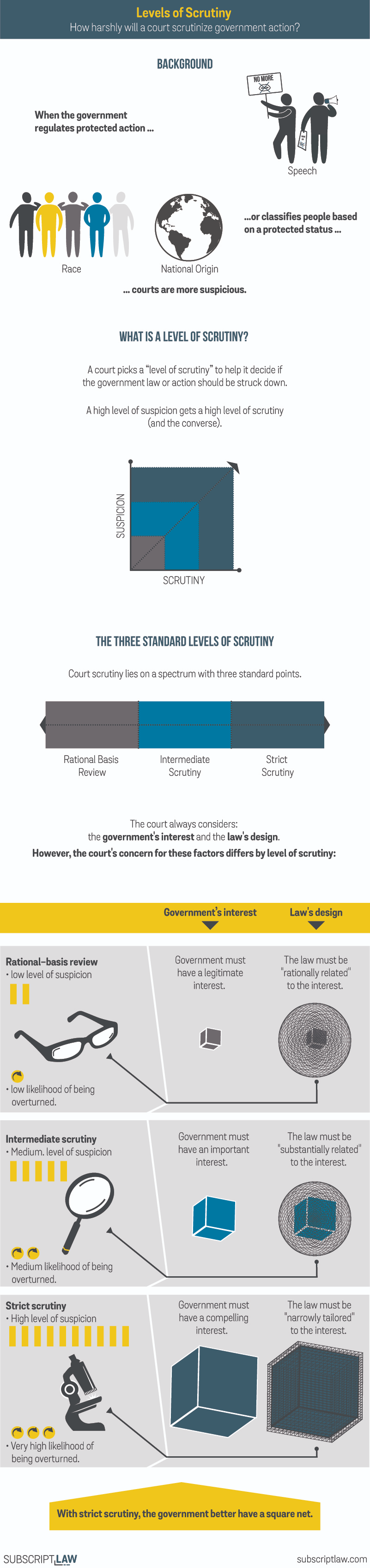

Levels of scrutiny (how demanding the court is)

This infographic organizes the three main tiers of judicial scrutiny on a spectrum (rational basis → intermediate → strict), showing how the government’s required justification becomes more demanding as the right/classification becomes more sensitive. It also visualizes the two core components of most scrutiny tests: the strength of the government interest and the tightness of the law’s “fit” (tailoring) to that interest. Source

A restriction is more likely to be struck down when it burdens a fundamental right or targets a protected class; it is more likely to be upheld when it regulates more routine areas of policy.

Strict scrutiny: The toughest judicial test; the government must prove a compelling interest and show the law is narrowly tailored (often described as the least restrictive workable approach).

Strict scrutiny is most associated with severe burdens on fundamental rights; it creates a strong presumption against the law unless the government’s justification is extraordinary.

Other common standards (in general terms)

Intermediate scrutiny: used in some sensitive contexts; the government must show an important interest and a close fit between the law and that interest.

Rational basis review: the most deferential; the law is upheld if it is reasonably related to a legitimate interest.

What Makes a Limit More or Less Constitutional

Even when the government’s goal is important, courts focus on design problems that suggest the government is restricting more liberty than necessary.

Narrow tailoring and “fit”

A law is more defensible when it:

targets the harmful conduct precisely, rather than sweeping in protected activity

uses clear, objective criteria to guide enforcement

leaves open meaningful alternative ways to exercise the right (when applicable)

Overbreadth and vagueness concerns

Restrictions become constitutionally suspect when:

overbreadth chills protected activity because the law covers too much

vagueness gives people inadequate notice of what is prohibited or invites arbitrary enforcement

Content neutrality and viewpoint neutrality (especially with speech)

This article explains the Supreme Court’s standard for evaluating content-neutral time, place, and manner restrictions on speech, breaking it into three elements: content neutrality, narrow tailoring to a significant governmental interest, and ample alternative channels. It’s a useful visual anchor for remembering how courts often uphold speech regulations when they focus on public safety or public order without targeting ideas or viewpoints. Source

Limits on expression are more likely to survive when they regulate without favoring:

particular ideas (viewpoints), or

particular subjects (content)

Typical Government Interests That Can Justify Limits

Courts commonly recognise interests such as:

public safety (preventing violence or panic)

public order (managing crowds, preventing obstruction)

rights of others (reputation, privacy, property, fair trials)

national security (in limited, highly scrutinised contexts)

administrative needs (effective operation of schools, prisons, workplaces), though these often come with special doctrines and deference

Why This Matters for AP Government

This subtopic explains why constitutional disputes are rarely “rights always win” or “government always wins.” The outcome usually depends on the strength of the government’s interest, the level of scrutiny, and whether the restriction is carefully drawn rather than overly broad or discriminatory.

FAQ

They look for interests of the highest order (e.g., preventing imminent harm) and often require evidence, not speculation.

Context matters: the same interest can be compelling in one setting and merely important in another.

Narrow tailoring asks whether the law targets the problem without unnecessary spillover.

Least restrictive means is stricter: if a less speech-restrictive (or liberty-restrictive) option would work comparably well, the government should use it.

Vagueness undermines notice, so people cannot tell what is allowed.

It also risks arbitrary enforcement, letting officials punish disfavoured speakers or groups while claiming to protect safety.

Yes. Courts may be more deferential when rapid action is needed and the risk of harm is high.

But deference is not unlimited; judges still examine whether restrictions are time-limited, evidence-based, and appropriately targeted.

They ask whether people still have realistic ways to communicate or act meaningfully, not merely theoretical options.

Alternatives that are far less effective, prohibitively costly, or practically unavailable may not satisfy constitutional expectations.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Explain how a government interest can justify limiting an individual constitutional right.

1 mark: Identifies that rights are not absolute and may be restricted to achieve a legitimate/important government interest (e.g., public safety).

1 mark: Explains that courts require justification and an appropriate fit (e.g., narrow tailoring/appropriate scrutiny).

(6 marks) A city bans all demonstrations within 1 mile of any hospital at any time, citing patient safety and emergency access. Assess the strongest constitutional arguments for and against the ban.

Up to 3 marks (for the ban): explains legitimate interest (patient safety/access); connects to maintaining order; notes that some restrictions can be permissible if properly justified.

Up to 3 marks (against the ban): argues poor fit (overbroad distance/time); notes chilling effect/overbreadth or vagueness; argues lack of narrow tailoring and availability of less restrictive alternatives.