AP Syllabus focus:

‘Procedural rights of the accused include the right to legal counsel, a speedy and public trial, and an impartial jury.’

Trial rights in criminal prosecutions reflect a constitutional commitment to fairness and legitimacy. These protections limit government power, reduce wrongful convictions, and increase public confidence by requiring reliable procedures before punishment.

Constitutional Source and Core Idea

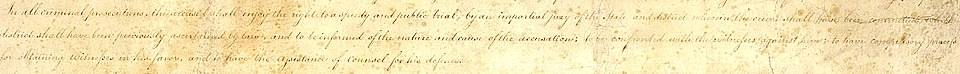

Most trial protections discussed here come from the Sixth Amendment, which regulates how the government conducts criminal prosecutions.

Cropped facsimile of the U.S. Bill of Rights showing the Sixth Amendment’s original text. Using the primary document helps students connect doctrinal terms (speedy trial, public trial, impartial jury, assistance of counsel) directly to the constitutional language. This is especially useful for FRQs that ask students to cite a specific constitutional provision. Source

In practice, Supreme Court interpretations set enforceable minimum standards for courts.

Why These Rights Matter

They reduce coercion and imbalance between the individual and the state.

They promote accurate fact-finding and lawful verdicts.

They make courtroom outcomes more publicly accountable.

Right to Counsel

The right to counsel means the accused can have a lawyer’s assistance at critical stages of the prosecution, including trial.

Right to counsel: A constitutional guarantee that a criminal defendant may be assisted by an attorney, including a court-appointed attorney when required by law.

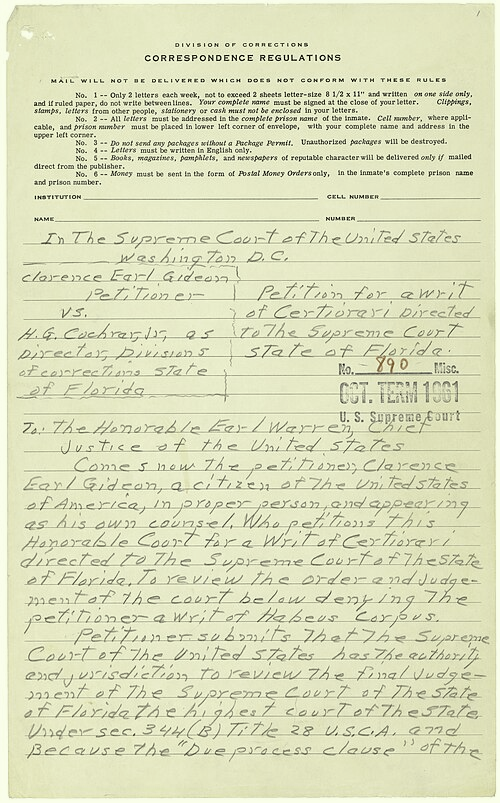

Counsel is essential because criminal procedure is complex and the state has professional prosecutors and investigative resources. A key Supreme Court milestone is Gideon v. Wainwright (1963), which required states to provide attorneys to indigent defendants charged with serious offences.

Handwritten petition for certiorari filed by Clarence Earl Gideon, the defendant in Gideon v. Wainwright (1963). The document underscores how the right to counsel functions as a practical safeguard for defendants who cannot navigate complex criminal procedure on their own. Pairing the case rule with the original filing helps students remember both the constitutional principle and the real-world problem the Court addressed. Source

What the Court Focuses On

Access: whether the defendant had a meaningful opportunity to be represented.

Fairness: whether the lack of counsel undermined the integrity of the proceeding.

Critical stages: points where legal advice can affect outcomes (for example, trial and certain pretrial proceedings).

Speedy Trial

The Sixth Amendment also guarantees a speedy trial, aimed at preventing long, unjustified delays that can harm the defendant and the justice system.

Speedy trial: A requirement that the government bring a criminal defendant to trial without unreasonable delay, protecting against prolonged detention and impaired defence preparation.

Courts consider harms from delay such as:

extended pretrial incarceration

anxiety and reputational damage

lost evidence or unavailable witnesses that weaken the defense

A common judicial approach weighs circumstances rather than applying a single rigid deadline, looking at the length of the delay, reasons for delay, the defendant’s assertion of the right, and prejudice to the defendant.

Public Trial

The Sixth Amendment promise of a public trial promotes transparency: trials should generally be open so the public can observe the fairness of proceedings.

Public trial: A principle that criminal trials are presumptively open to the public to promote accountability and discourage misconduct.

Public access helps:

deter judicial or prosecutorial abuse

encourage truthful testimony

strengthen legitimacy of verdicts

Courts may allow limited closure in narrow situations (for example, to protect vulnerable witnesses), but closures must be justified and tailored rather than routine.

Impartial Jury

For many serious criminal cases, the Constitution protects the right to a jury that is unbiased and selected through fair procedures.

Impartial jury: A group of jurors chosen through lawful selection procedures who can decide the case based on evidence and law, free from bias or improper exclusion.

Key ideas include:

Jury as community check: jurors act as a buffer between the accused and the government.

Voir dire: questioning to identify bias and ensure jurors can follow the law.

Non-discrimination: jury selection cannot intentionally exclude jurors based on race; Batson v. Kentucky (1986) limited race-based peremptory strikes.

What “Impartial” Requires in Practice

jurors must not have fixed opinions about guilt

procedures must reduce the risk of stacking the jury

courts must respond to credible claims of bias that threaten a fair verdict

FAQ

Yes, but waiver must be knowing and voluntary.

Courts typically ensure the defendant understands charges, possible penalties, and disadvantages of self-representation.

Not constitutionally.

Courts often use balancing factors, while legislatures may add statutory deadlines that are stricter than the constitutional minimum.

No.

“Petty” offences (typically with short maximum penalties) may be tried without a jury, depending on jurisdiction and offence severity.

Dismissal of the charges is a common remedy.

Whether dismissal is with or without prejudice can depend on governing law and the seriousness of the violation.

Heavy publicity can risk bias.

Courts may use extended voir dire, jury instructions, sequestration, or change of venue to protect impartiality.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Describe one purpose of the Sixth Amendment right to a public trial.

1 mark: Identifies that trials are presumptively open to the public.

1 mark: Explains a valid purpose (e.g., transparency/accountability, deterring misconduct, increasing legitimacy).

(6 marks) A defendant charged with a serious felony cannot afford a solicitor. The judge tells the defendant to represent themselves because the court is “too busy” to appoint counsel. Assess whether this violates the defendant’s constitutional trial rights, using one relevant Supreme Court case.

1 mark: Identifies the right to counsel as the relevant trial right.

2 marks: Applies Gideon v. Wainwright (1963) to explain that indigent defendants in serious cases must be provided counsel.

1 mark: Explains why workload/administrative convenience is not a sufficient justification.

1 mark: Links denial of counsel to fairness/ability to mount a defence.

1 mark: Reaches a clear judgement that the defendant’s constitutional right was likely violated.