AP Syllabus focus:

‘Protections against unreasonable searches include limits on warrantless access to cell phone data and constraints on bulk metadata collection.’

Modern Fourth Amendment disputes often involve digital information. Courts must decide when police need a warrant to access data on phones or obtain metadata from providers, balancing privacy with law enforcement needs.

Fourth Amendment basics in the digital context

The Fourth Amendment protects against unreasonable searches and seizures. In practice, courts ask whether the government action intrudes on a person’s reasonable expectation of privacy and, if so, what process is required.

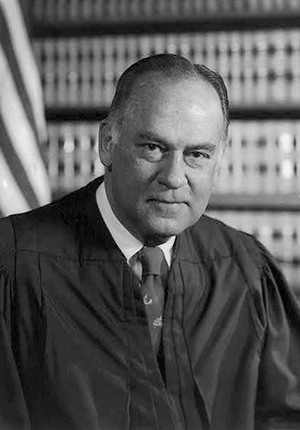

Portrait of Justice Potter Stewart, author of the majority opinion in Katz v. United States (1967). Katz is foundational for the “reasonable expectation of privacy” approach that later shapes digital Fourth Amendment disputes. Pairing the doctrine with a primary-source image helps students connect abstract tests to the Court and its decision-making context. Source

Warrants and the default rule

A warrant supported by probable cause is the usual safeguard for intrusive searches. Digital tools complicate this because:

Cell phones store vast quantities of personal information.

Metadata can reveal patterns (location, contacts, timing) even without message content.

Data may be held by third parties (carriers, app companies), raising doctrine questions.

Cell phones: limits on warrantless access

Why phones are treated differently

In Riley v. California (2014), the Supreme Court held that police generally may not search the digital contents of a cell phone seized during an arrest without a warrant. The Court emphasised that phones are unlike physical containers because they:

hold extensive, sensitive records (photos, messages, health and financial data)

provide long-term, searchable histories

can expose information about many other people, not just the suspect

Practical implications

After Riley, a lawful arrest does not automatically justify browsing a phone’s data. Police may still:

seize and secure the phone to prevent destruction of evidence

seek a warrant describing what data may be searched

rely on narrow exceptions in true emergencies (courts scrutinise these closely)

Metadata: constraints on bulk collection

Metadata is not the content of communications, but it can be highly revealing.

Metadata: information about a communication or digital activity (such as time, duration, recipient, device identifiers, or location), rather than the message’s content.

Third-party doctrine pressure

Earlier cases such as Smith v. Maryland (1979) suggested reduced privacy in information voluntarily shared with a company. Digital life, however, forces constant sharing with service providers, so the Court has limited automatic application of that principle for certain tracking data.

Location metadata and warrants

In Carpenter v. United States (2018), the Court held that obtaining historical cell-site location information (CSLI) is a search in many circumstances, so the government generally must get a warrant.

A cellular base-station (cell tower) with multiple antenna arrays that handle phone connections. Each connection between a phone and a tower can produce time-stamped provider records (CSLI), which—when aggregated—can reveal a user’s movements over time. This visual helps explain why the Court treated long-term location metadata as especially privacy-sensitive in Carpenter. Source

Key reasoning:

CSLI can reconstruct a person’s movements over time

long-term location tracking is deeply revealing

users do not meaningfully “choose” to share CSLI in ordinary phone use

Bulk metadata concerns

Debates over collecting large datasets (for example, many users’ location points or calling records) focus on whether the scope becomes unreasonable because:

the collection is broad rather than targeted

it enables detailed inferences about private life

it risks misuse, retention, or secondary analysis beyond the initial purpose

What students should be able to do with this topic

Distinguish device searches (phone contents) from provider-held records (metadata).

Explain why Riley strengthened warrant requirements for phone data after arrest.

Explain why Carpenter imposed warrant constraints on certain location metadata, despite third-party involvement.

Connect these rulings to the syllabus point: limits on warrantless access to cell phone data and constraints on bulk metadata collection.

FAQ

Often, “content” (what you said) receives stronger protection than “non-content” data (routing or signalling information), but modern cases recognise that some non-content data can be just as revealing.

Providers’ specific records and how they are generated can affect outcomes.

A geofence warrant seeks data on all devices near a location during a time window. Critics argue it is overbroad and risks sweeping up many innocent people.

Supporters argue it can be narrowed by time, place, and later filtering.

Not necessarily. Data may persist via backups, synced devices, or provider logs.

Legal issues then shift from a device search to compelled access to cloud-stored records and what process is required.

Courts have differed. Issues include self-incrimination principles and whether providing access is “testimonial”.

Many jurisdictions treat passcodes more protectively than fingerprints/face unlock, but rules vary.

Minimisation limits what is kept, used, or shared after collection (e.g., deleting irrelevant records). Retention rules govern how long data is stored.

These policies can influence whether a programme is viewed as reasonable, even when some collection is permitted.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (3 marks) Explain one reason the Supreme Court in Riley v. California (2014) generally required a warrant to search the digital contents of a mobile phone seized during an arrest.

1 mark: Identifies that phones contain vast quantities/types of personal data.

1 mark: Explains why that makes a phone unlike a physical container found on an arrestee.

1 mark: Links this difference to the need for a warrant to prevent unreasonable searches.

Question 2 (6 marks) Using Supreme Court reasoning, compare how the Fourth Amendment applies to (a) police searching a suspect’s mobile phone and (b) government acquisition of historical location metadata from a mobile provider.

1 mark: Correctly describes phone-content searches as highly intrusive due to depth/breadth of stored information (Riley).

1 mark: States that a warrant is generally required for phone digital contents even incident to arrest (Riley).

1 mark: Identifies historical CSLI as location metadata that can track movements over time (Carpenter).

1 mark: States that obtaining historical CSLI is treated as a search in many circumstances (Carpenter).

1 mark: Explains why third-party possession does not automatically remove privacy expectations for CSLI (limits on third-party doctrine).

1 mark: Makes a clear comparison (similarity and/or difference) in how warrants/expectations of privacy apply across the two contexts.