AP Syllabus focus:

‘Procedural due process requires officials to use fair, non‑arbitrary methods when making decisions that affect constitutional rights.’

Procedural due process is the Constitution’s demand for fair decision-making. It limits how government acts, not just what government may do, by requiring reliable, non-arbitrary procedures before important deprivations occur.

Core idea: fairness in government procedures

Procedural due process focuses on the steps government must follow when it threatens to take away protected interests. It aims to reduce arbitrary outcomes, constrain biased decision-makers, and improve accuracy and legitimacy.

Procedural due process: Constitutional requirement that government use fair, non‑arbitrary procedures (such as notice and a hearing) before depriving a person of life, liberty, or property.

Procedural protections generally apply only when there is state action (government conduct, not purely private conduct).

When procedural due process is triggered

Protected interests

Due process requirements arise when government threatens to deprive someone of:

Life

Liberty (e.g., physical freedom; sometimes reputational harm tied to a legal status change)

Property (often includes legal entitlements created by statute or policy, such as certain public benefits or continued enrollment/employment under defined rules)

A key threshold question is whether the interest is genuinely protected; if not, the Constitution may not require additional procedure beyond ordinary political or administrative processes.

Federal vs. state application

The Fifth Amendment applies due process limits to the national government.

The Fourteenth Amendment applies due process limits to state and local governments.

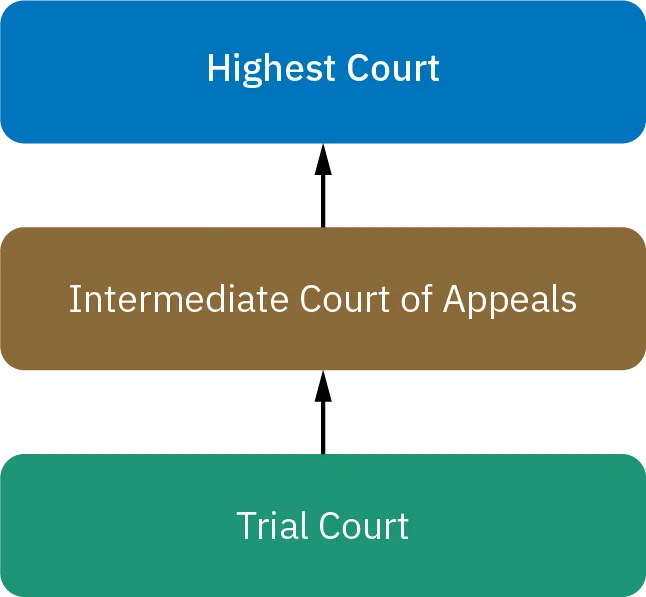

This diagram summarizes the basic hierarchy of U.S. courts: trial courts, intermediate appellate courts, and the highest court. It helps connect procedural due process to the idea that procedures create a record that can be reviewed on appeal for legal error. In practice, the availability of appellate review shapes how much emphasis institutions place on notice, hearings, and written reasons. Source

What “fair, non-arbitrary procedures” usually include

Procedural due process is flexible, but common constitutional minimums include:

Notice

Timely notice that government intends to act

Notice should state the reason for the action and the rule/evidence at issue where feasible

Opportunity to be heard

A meaningful chance to respond before the deprivation when practical

The hearing must occur at a meaningful time and in a meaningful manner (the Constitution does not always require a full courtroom trial)

Neutral decision-maker

Decision-makers should be sufficiently impartial

Procedures should reduce risks of conflicts of interest or prejudgment

Ability to present information

Opportunity to present the person’s side of the story, including relevant documents and witnesses when appropriate

In higher-stakes settings, procedures may also include limited confrontation or cross-examination, depending on context and need for reliability

Reasoned decision and record (often)

Especially in more formal settings, a decision may need to be grounded in the record and consistent with stated standards, helping prevent arbitrary enforcement

How courts decide how much process is “due”

The Supreme Court does not require the same procedure in every setting; it uses balancing to match procedures to the stakes and risks.

Mathews v. Eldridge balancing (framework)

Courts commonly weigh:

The private interest affected (how serious the loss is)

The risk of erroneous deprivation under current procedures and the likely value of added safeguards

The government’s interest, including administrative costs and the need for efficient action

This explains why a brief, informal hearing can satisfy due process in some contexts, while other contexts demand more formal protections.

A key example of procedural due process in practice

Goss v. Lopez (1975)

In public schools, the Court held that short suspensions implicate protected interests and require basic fairness:

Notice of the charges

An opportunity for the student to give their side

The case illustrates a recurring principle: even when government has strong authority (like maintaining school order), it must still use fair, non‑arbitrary methods when making decisions that significantly affect individuals’ protected interests.

FAQ

No. The required procedure depends on context and balancing.

Many situations permit informal hearings if they meaningfully reduce arbitrariness and error.

Notice is informing someone the government intends to act and why.

A meaningful opportunity to be heard is the real chance to respond in time to influence the decision.

Written submissions can be sufficient where credibility is not central and the stakes are lower.

Where credibility and factual disputes matter, in-person procedures may add value.

Emergency action can be constitutional if immediate action is necessary.

Due process typically requires a prompt post-deprivation hearing to reduce the risk of arbitrary error.

Not automatically. Internal rules help show fairness, but constitutional due process is a separate baseline.

Courts ask whether the procedures are fair and non-arbitrary given the interests at stake.

Practice Questions

(2 marks) Define procedural due process and identify one procedural safeguard it commonly requires.

1 mark: Accurate definition of procedural due process (fair, non-arbitrary procedures before deprivation of life, liberty, or property).

1 mark: One correct safeguard identified (e.g., notice, opportunity to be heard, impartial decision-maker).

(6 marks) A state university expels a student for misconduct based solely on an anonymous written complaint, without giving the student details of the allegation or any chance to respond. Explain how procedural due process would evaluate the fairness of the university’s procedure.

1 mark: Identifies state action and Fourteenth Amendment due process applicability.

1 mark: Explains triggering issue: deprivation of a protected interest (e.g., continued enrolment/education as a property/entitlement interest under university/state rules).

1 mark: Explains lack of notice as a due process flaw (insufficient information/time).

1 mark: Explains lack of opportunity to be heard as a due process flaw (no hearing/response).

1 mark: Uses balancing logic (Mathews factors: private interest, error risk, government burden) to justify need for more safeguards.

1 mark: Connects to minimum fairness principle (non-arbitrary, reliability-enhancing procedures; anonymous complaint alone increases error risk).